INTRODUCTION

I n December 1969, Stephen Shamberg resigned as president of one of the most powerful neighborhood organizations in Chicago, the Lincoln Park Conservation Association. In his letter of resignation, he offered a blunt assessment of the movement.

We are assisting, he wrote, in the destruction of our community.

For fifteen years, LPCA had fought to transform its piece of the citys North Side, just two miles from downtown on the shores of Lake Michigan. And indeed, Lincoln Park had been transformed. Dilapidated homes boasted new windows and paint; developers clamored to invest where banks had refused to lend; and new businesses were opening. But not all of its members were feeling triumphant. Instead, they found themselves bitterly divided: Some feared their decades of work might soon be rolled back. Others believed it deserved to be.

Back in the 1940s, when the antique dealers, historians, and lawyers were just beginning their campaign to restore Lincoln Parks Victorian-era grandeur, they had felt no such ambiguity. Back then, the stakes had seemed very different to them, their campaign to remake the neighborhood almost utopian.

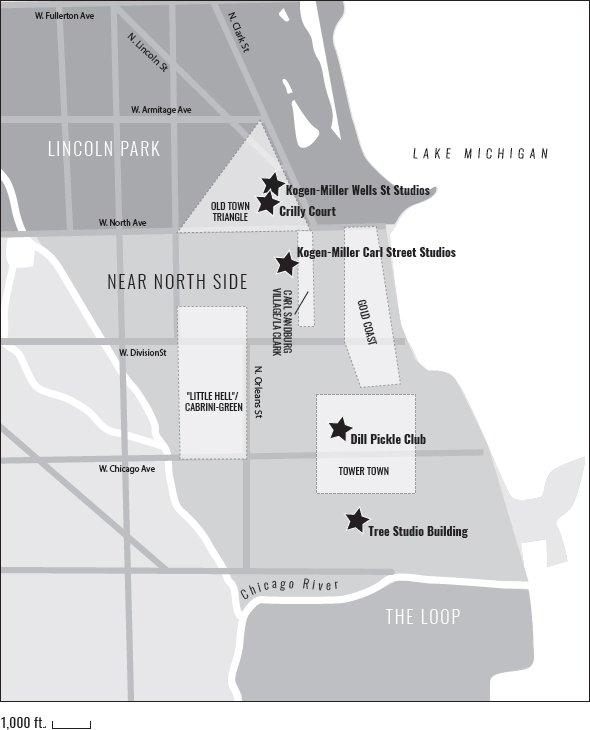

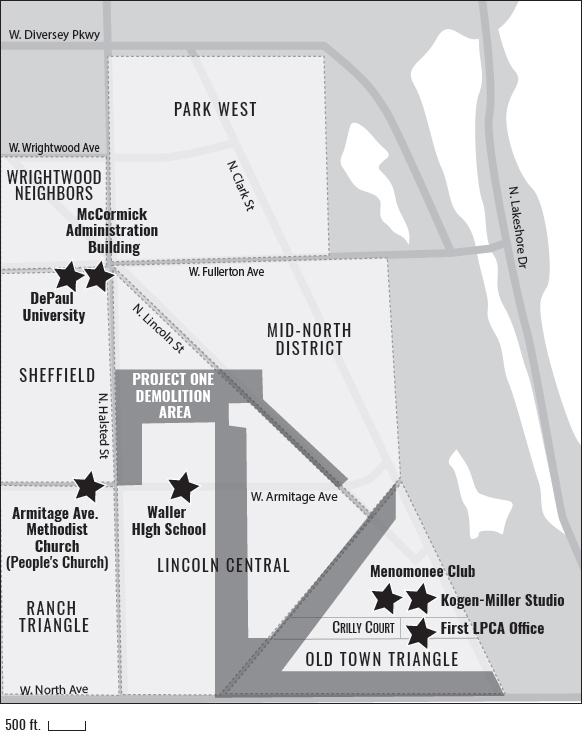

In the years after World War II, Lincoln Park was an aging neighborhood of walkup apartments, the lake on one side and an industrial riverfront on the other. Close to downtown Chicago, and even closer to the elite Gold Coast area, its residents incomes nevertheless ranked sixtieth out of the citys seventy-five neighborhoods. Despite a notable lack of racial integrationmore than ninety-eight percent of Lincoln Parkers were whitealmost the entire neighborhood was redlined, or cut off from home loans for purchases or renovations, a type of disinvestment often targeted at black communities. Home to more than 100,000 people, busy commercial streetscapes, and longstanding religious and ethnic communities, most members of the white middle class nevertheless believed it was a neighborhood without a future. For them, Lincoln Park was destined for further economic decline, perhaps even racial integration from the small black community to the southand, if things could not be turned around, annihilation through government-led slum clearance.

At the same time, a small but growing movement of white professionals viewed Lincoln Park as a gem waiting to be polished and reclaimed. In the late 1800s, families of means had built stately brick homes and apartments on the rubble of the Great Fire of 1871, before ultimately abandoning them in the march towards the suburbs. Now postwar rehabbersgenerally professional-class white homeowners who bought and renovated old homescited that history as proof Lincoln Park deserved a more illustrious future. If they fixed up the old homes and modernized nearby streets and storefronts, they insisted, Lincoln Park might enjoy every advantage of a new suburban subdivisionwith all the history, culture, and convenience of the city. Its future might not be decline and demolition, but rebirth as a new kind of community that combined the best of both worlds.

But things had changed by 1969. People no longer wondered whether middle-class white people might settle down in an old urban neighborhood like Lincoln Park: It had already happened, and much of the eastern side of the community was now well above citywide averages in income and education. The new question seemed to be whether they could leave room for anyone else. As incomes rose, so did rents; each home renovationincreasingly performed by professional investors as much as individual familiesincreased property values. Meanwhile, the urban renewal program LPCA had lobbied for had demolished entire streetscapes, displacing thousands of people who were disproportionately low-income, Latino, or black.

Many now wondered if the future of Lincoln Park was the social homogeneity of the suburbs transplanted to the urban core. Shamberg was not alone in questioning whether the movement he led might be ruining the neighborhood it had meant to save.

The Battle of Lincoln Park traces the rehabbers path from idealism in the 1940s and 1950s to existential crisis in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and Lincoln Parks path from a predominantly working class neighborhood to one of the wealthiest communities in the Chicago area. The rest of the book is divided into three parts. , The Invention of Old Town, follows the earliest bohemian rehabbers on the North Side and their more middle-class successors who laid the groundwork to bring urban renewal to Lincoln Park.

, The Conservation of Lincoln Park, covers the period when the rehabbers aggressively pursued their own private neighborhood improvement program as federal officials dragged their feet.

, The Battle of Lincoln Park, tells the story of the rising resistance that emerged after the start of the federal renewal program and fought for its own visions of the neighborhood, and the uneasy resolution of that conflict.

Along the way, this book will try to show how the rehabbers work interacted with larger social and economic systems to create Lincoln Park as it exists today: the heart of a predominantly white zone of concentrated affluence that encompasses more than half a million people over a large part of Chicagos North Side. Just as the twentieth century history of redlining, white flight, and racist violence helps us understand why cities like Chicago have large, disproportionately black and Latino areas of disinvestment, the twentieth century history of slumming, conservation movements, and rehabbing helps explain why we have large, predominantly white, areas of concentrated investment.

Much of Lincoln Parks path in the years after World War Two will seem familiar to people who live in gentrifying neighborhoods nowfrom the way that new middle-class residents praised the neighborhoods authenticity and diversity, to complaints about commercialization, to the organizing taken up by lower-income residents and their allies to preserve their place in the neighborhood. (By gentrifying, I mean a growth in professional class residents, generally without social ties to the prior residents of the neighborhood, and usually white.) If we recognize ourselves and our neighborhoods today in the earlier experiences of Lincoln Park, we may have a better sense of where we are going, and why.

![Hertz - Scheik Hassan, Lystspil i tre Acter [in prose and verse]](/uploads/posts/book/182877/thumbs/hertz-scheik-hassan-lystspil-i-tre-acter-in.jpg)