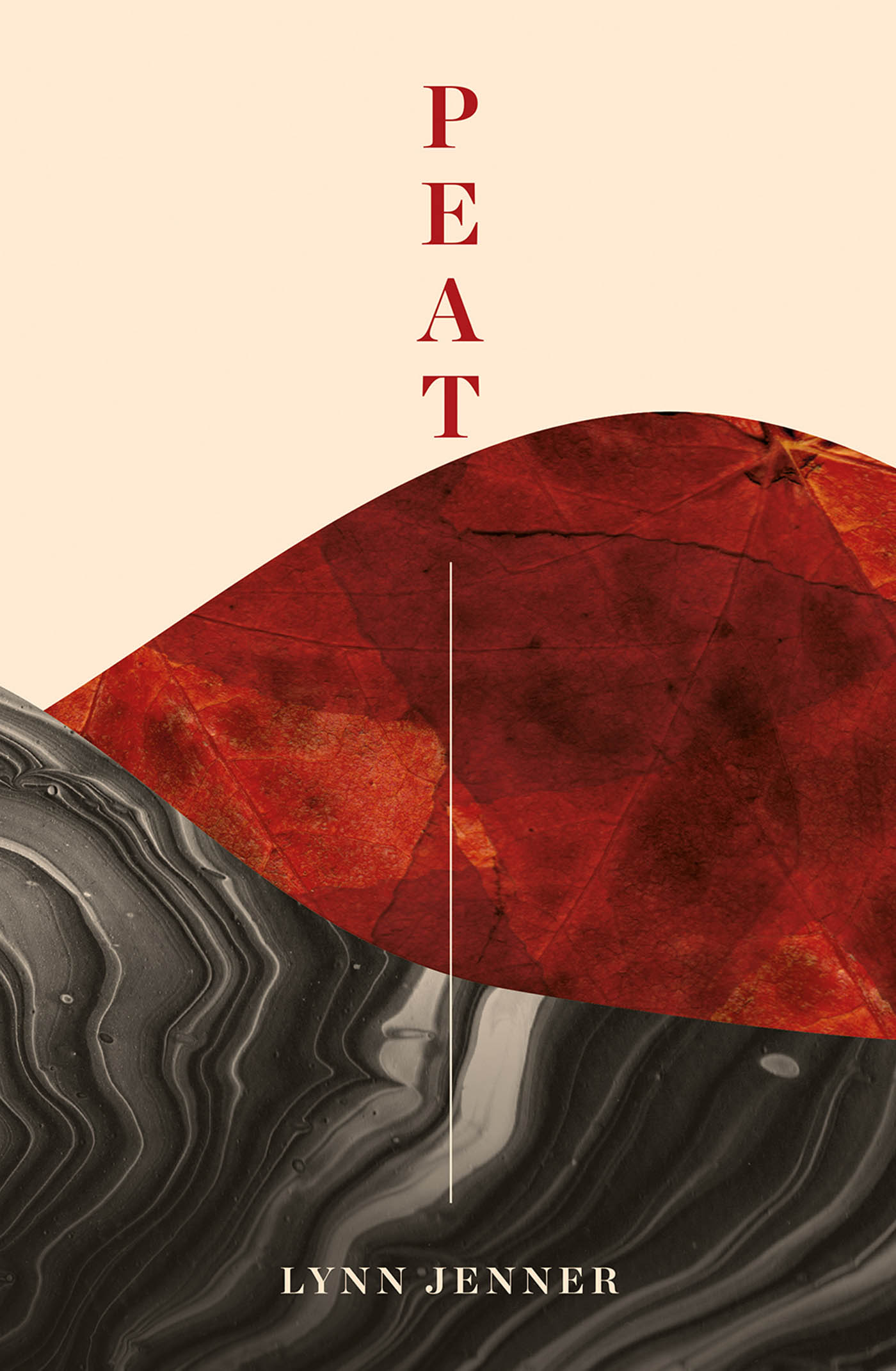

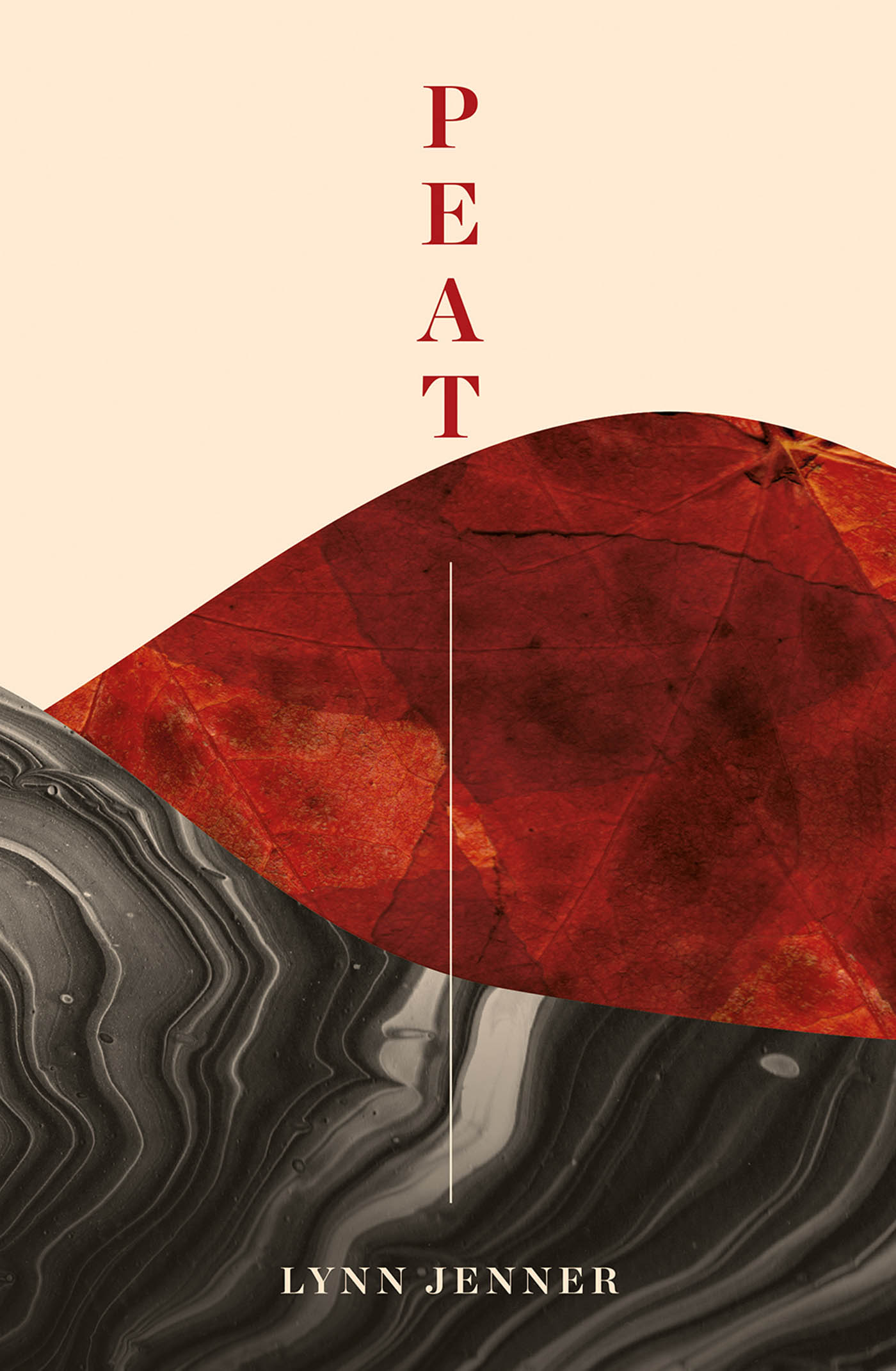

I can think of no other piece of New Zealand writing that is really like Jenners seemingly casual, but carefully constructed engagement of one life with another, with its play of enduring values against the grain of immediate contemporary experience.

VINCENT OSULLIVAN

intriguing and thought provoking; a cornucopia of literary history, biography, memoir, politics, community activism and stimulating ideas. Such an unlikely juxtaposition of subjects shouldnt work but it does!

MANDY HAGER

Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2019

Copyright Lynn Jenner

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-853169-4 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859223-7 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859224-4 (Kindle mobi)

ISBN 978-1-98-859225-1 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

Editor: Anna Hodge

Index: Barbara Frame

Design/layout: Fiona Moffat

Author photo: Simon Neale

Cover and maps: Charlotte McCrae

Ebook conversion 2020 by meBooks

Peat is an archive. The black soil, the tea-coloured water, the sticks and the great trees. Whole ecosystems from the past are safely stored down there.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The essays in the first part of Peat are accompanied by two glossaries titled One Starless Night and The Prettiest Road in New Zealand.

When I began Peat, both Charles Brasch and the building of the Kpiti Expressway were new subjects to me. One Starless Night is a glossary of my developing acquaintance with the work of Charles Brasch; The Prettiest Road in New Zealand is a glossary of my acquaintance with the building of the Kpiti Expressway. The framework of a glossary allowed me to explore the language of these two subjects and to record questions and reflections as I spoke to people, read books, newspapers and poems and formed my own ideas. The glossaries run parallel to the essays, as research often runs parallel to or underneath other writing. They can also be read as stand-alone pieces.

A small proportion of glossed theme-words are highlighted in the essays. Those linked to One Starless Night are marked with the symbol *, and those linked to The Prettiest Road in New Zealand are marked with the symbol .

Together, these twenty-seven theme-words tell the story of Peat.

A Necessary Protection

How CAN YOU EVER explain the reasons why you like someone or why you are drawn to explore a certain way of living or a way of thinking? There must have been a day that I started looking out for places Charles Brasch* mentioned or books he had written but I didnt mark the first Charles Brasch day on the calendar. I can say that I noticed Braschs presence, and formally decided to make his acquaintance, in 2013, the year they started to build the Kpiti Expressway. The Expressway was on the mind of everyone in Kpiti then. It was everywhere. The signs, the flags, the trucks, the newsletters, the radio interviews, the maps, the job ads it was an Occupation. And then Brasch arrived. Or, more correctly, I went looking for him. That was the order.

As the Expressway showed itself, arriving like an army in each new location along the route, I knew I needed the close company of a writer as a bulwark against all its enacted power and concrete. I needed to gather up pages and pages of words and take them inside with me, to a place where machines could not follow. I needed to make a word-nest, to read beauty as a form of psychic acceleration. Some world of my own should be prepared, somewhere meditative, cryptic or sublime. I was very surprised to find in myself this vestige of the idea that lyricism can be an actor in the material world, but I have learned to follow any literary or artistic suggestions that the universe provides, at least as far as an initial investigation.

I was attracted to Brasch by the c in his name (a hint of Jewishness which he decided to retain), by his decision that Landfall would contain non-fiction commentaries on contemporary issues, and by what another writer described as his off-putting tone of high seriousness. I suspected I might like this tone because I like people who are serious about their activities, and because I am serious myself, although in a low way. Of course I was intimidated by the whole notion of Charles Brasch because he was such a famous person. I knew almost nothing about him except that he was a poet whose work I couldnt relate to when I was young, that he was often uncomfortable here in New Zealand but wrote poems about the land, and that he had founded the literary journal Landfall, which itself intimidated me. But once you have decided to begin, it is just a matter of choosing a doorway.

I wanted a back-door beginning, something that allowed me to be in Braschs presence without being in any sense accountable, so I started by asking the Special Collections librarian for permission to visit the books from Charles Braschs library, now housed in the University of Otago Library. I wanted to look at books that had been Braschs books and touch them, which I did. Those books were the tools of his trade. They are personal and yet public objects. The collection ends when Braschs life ends. There is something intimate about that.

Dear Mr Brasch

On Monday last I visited your library at the Special Collections section of the University of Otago Library. I may not be telling you anything you dont know already, but I thought I should say that those footsteps, those probing fingers and that scratching pencil noise were all me.

When the librarian asked why I wanted to come and visit these books as if they were people, or this collection as if it were you, and told me that the books in your library are just books and most or perhaps all of them are available in other places, I produced only a sort of mumble about instinct. I am glad that I didnt have to explain my visit to you in person, because we dont know each other and it would have been awkward. I would probably have done more mumbling about the land and the people or our shared Dunedin heritage and that wouldnt have helped. After all, your Dunedin and mine were very different.

All I could say to the librarian, in answer to his very reasonable question, was I just want to see these books in the physical context of the collection. Not 100% rational. In reply he sent me this long thin message, which I read as a signal flag that the channel was clear for me to proceed, and a bright fluttering ensign of the miracle and wonder of libraries.

Next page