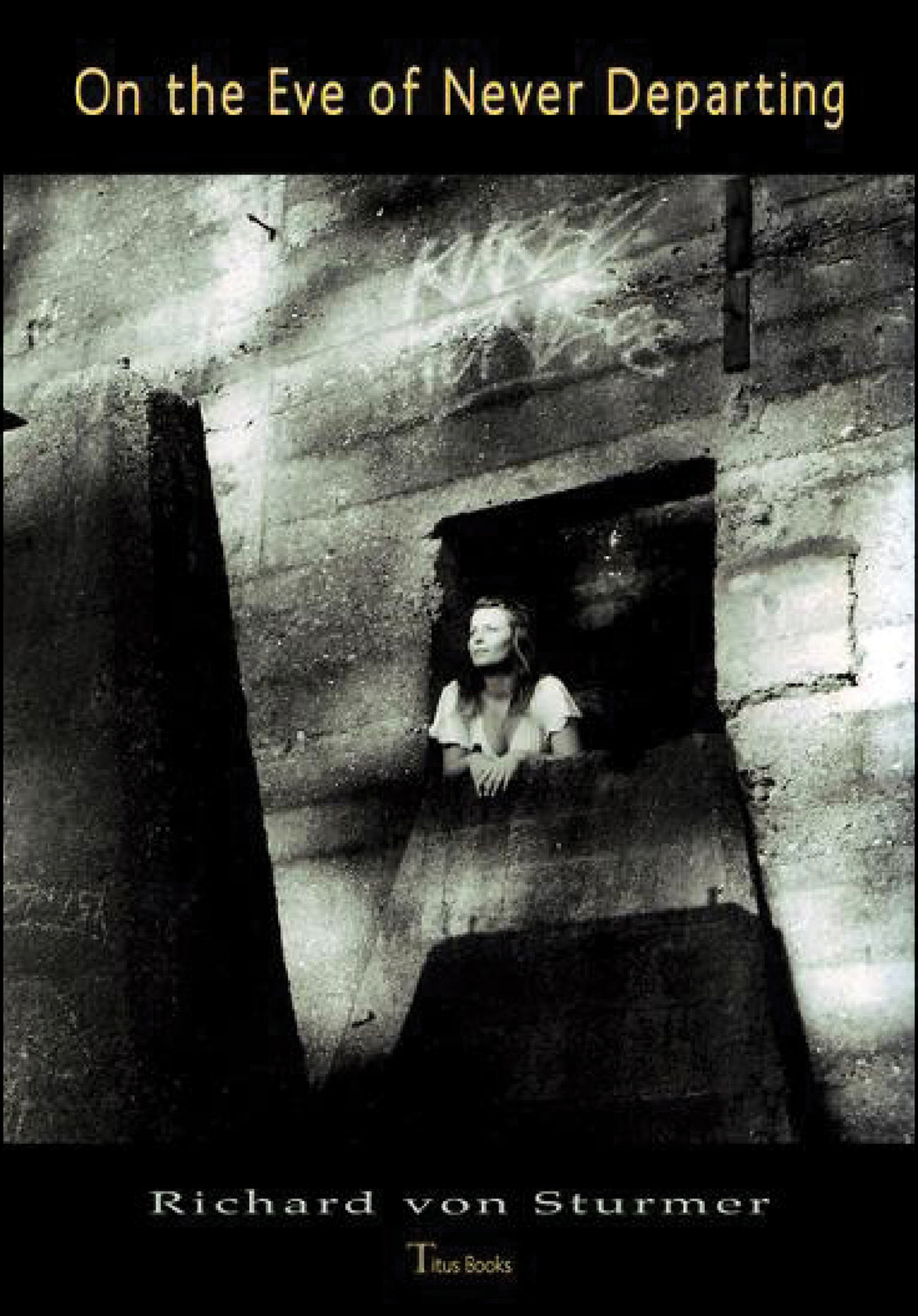

ISBN: 978-1-877441-63-9

Richard von Sturmer 2009, 2020

This publication is copyright.

Any unauthorised act may incur criminal prosecution.

No resemblance to any person or persons living or dead is intended.

On the Eve of Never Departing was first published by Titus Books in 2009

1416 Kaiaua Road, Mangatangi

New Zealand

www.titus.co.nz

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

Nothing needs to be done

On the eve of never departing.

Fernando Pessoa

Seclusion

The early morning light slips through a gap in the curtains. Outside his window, the unnamed bird continues to produce its single note, without missing a beat, and he finds himself awake. At that moment, the glass on his bedside table materializes out of the darkness. Dust motes are glowing in the water, and the writer observes how the oval surface, halfway up the glass, is perfectly reflected by the curve of the rim. Two transparent lenses have formed, one of water and one of air. He blinks and clears his throat, as if hes about to speak; but theres nothing to say. The bird has fallen silent, and the sparrows are beginning to chirp.

The first thing he does, after getting out of bed, is to put on his grey jersey, the one with holes in both sleeves. This is a way of serving notice to himself that, instead of venturing outside and appearing in public, he will remain firmly indoors and work at his desk. But before this he has to feed the cat, who is already rubbing herself against his legs. The cold morning air has raised the hairs on his calves, and he notes how these hairs, pressed flat by a body of fur, spring back into place when the cats moves away.

~

Looking out his small, oval window into the infinite blackness, the astronaut feels uncomfortable. Its not a matter of his bulky suit, whose confines he is now accustomed to inhabiting, but more a question of his position in the overall arrangement of things. Unable to penetrate the depths of space, he has to remain on the periphery, on the threshold, tied by invisible apron strings to his mother planet. And even if he could cut himself loose and head off in a straight line, he would be dead more emphatically dead than a mummified king from one of the Egyptian dynasties before he reached a suitable destination. And what is suitable? Some planet that would not crush him with its gravity or poison him with its gases; a planet not too hot and not too cold, with just the right amounts of oxygen and sunlight. When he tries to imagine such a place, he always comes back to the earth.

~

A disorderly platoon of silvereyes makes its way through the paspalam and surrounds the back deck. Flying from stem to stem, the tiny birds appear to enjoy the stalks bending beneath their weight; theyre able to exert a material presence while displaying their intrinsic lightness and agility. Swaying from side to side on the stems, they chirp to each other, or hang upside down and peck at the seed-heads. Paspalam, the writer would have informed him, comes from the Latin paspale : the finest meal, a tasty morsel. But the meditator doesnt concern himself too much with words. Its enough that one silvereye, bolder than the rest, lands beside him on the deck. He admires the green and olive-grey of its feathers, and the perfect circles of white around each of its eyes. The bird, for its part, takes note of him, dressed in his faded robe and seated on his brown meditation cushion.

His world, for the next six weeks, consists of two small huts linked by a wooden walkway. One hut, his residence, has a bed, a chair and a long shelf, which serves him as a desk; the other hut is just the smallest of kitchens with a sink and a gas stove. Connected to a water tank out the back, the kitchen has been built beside a stand of manuka; or as the meditator likes to think of it, the huts and their walkway are moored to the manuka and encircled on three sides by a sea of paspalam.

At midday he hears the heavy wing-beats of two woodpigeons who settle in a large eucalyptus tree. The tree stands alone in a nearby field. Before they land on its branches, the sound of their wings cuts through the buzzing of flies and the sizzling of cicadas. The meditator stops counting his exhalations, uncrosses his legs, and leaves the darkness of his hut. To his surprise, one of the woodpigeons, flying away across the valley, suddenly breaks and turns upwards, spreading out its wings to hover in midair, for a brief moment like an angel. Then it flips over and dives into the bush below. The woodpigeon repeats this manoeuvre several times. Each time the angel appears before him in the bright open space; each time he catches himself holding his breath.

~

From the doorway, the writer looks back at his unmade bed; the impression left by his body is still visible, right in the middle of the mattress, surrounded by the swirl of his top sheet and a pile of rumpled blankets. The tides gone out, he observes, as if an image were needed to express the general feeling of absence. Only after saying these words does he detect the smell of salt; a forgotten smell, the smell of aloneness. He reminds himself that its been ages (or, more precisely, another age) since anyone lay beside him. Does he even have an extra pillow, or would he have to go into the living room and find his partner an appropriate cushion? If he were to sleep with another person, a major adjustment would have to be made to his erratic nocturnal schedule, which has him getting up at any hour of the night to jot down a few lines, to consult a particular text, or to read a favourite passage.

After feeding the cat, he places a coffee bag in his small white teapot, pouring in the nearly boiled water while a saucepan of milk heats up on the stove. He then adds the warm milk directly to the teapot, and pours his coffee into a teacup. This somewhat perverse way of doing things gives an indication of how far he has strayed from normal conventions; both from coffee culture with its freshly ground beans and elegant, stainless steel percolators, and from the ancestral world of tea, for which his white pot and willow pattern cup were clearly designed. But it doesnt matter; the coffee is just right. Not bothering to sit down at the dining table, he eats a piece of toast, spread with honey, while standing beside the kitchen bench.

With the sun obscured behind a bank of clouds, the patches of daylight in his study are dull and pallid. The writer would like to close the door behind him and retrace his steps along the corridor to his bedroom, leaving the study and the patches of light to themselves. But this would be retreat, and he is determined to start his work today. In this spirit, he sits down at his desk and picks up one of his pens, which lies in the shade of a large stack of papers. The top sheet is pure white, and the metal of his pen feels cold between his fingers.

He realizes, from the very beginning of the day from the voice of the unnamed bird, the motes of dust in his glass of water, through the image of his unmade bed and his odd approach to brewing coffee, and on to the patterning of sunlight and shadows in his study that hes been making an uninterrupted series of observations, providing himself with a sort of running commentary. But for what purpose? He has primed himself to begin a narrative, to craft a long piece of fiction which will encompass a number of different characters involved in intense and even dramatic situations, set against a remote, imposing landscape. And yet what captures his interest is simply the perpetual unfolding of mundane details. Its difficult to know how to proceed when his intent and his attention are going in different directions. He feels like he has reached an impasse, in the same way that Alan, the main protagonist of his story, finds his ascent of the mountain blocked by a steep and imposing cliff. But the last thing the writer wants to do is to create some kind of allegory. The mountain must be a real mountain, he tells himself. At that moment, the first sentence slips out from under the nib of his pen: The granite wall was featureless and offered no footholds.