For Sheelagh

CONTENTS

Canterbury City Council Museums

Barron (A.R.Clark), Bridge

Fisk-Moore, Canterbury

Humanities Research Center, Texas

Barron (A.R.Clark), Bridge

Alvin Langdon Coburn

Peter Waugh

British Library, Ashley MS 2953 f.47

Leeds University Library

Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club

National Monuments Record

Bodleian Library MS Add.C165 f.78r

Canterbury Cathedral Archives

CCA-DCc-PRINDRAW/4/B/4

Kent Archives

Kent Archives

Fisk-Moore, Canterbury

John Urmston

drawn by John Gilkes

Literary Bishopsbourne

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey

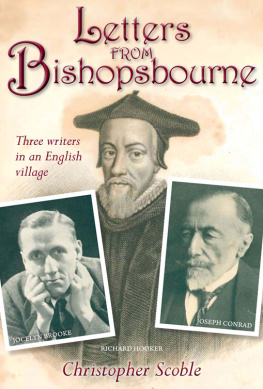

My first debt of gratitude is to Jonathan Hunt, the leading authority on Jocelyn Brooke, who has been most generous in sharing with me some of the hard won biographical detail of his research and in reading over my text the errors, of course, remain all mine. We all look forward with impatience to his forthcoming definitive work on Brooke. I am grateful too for the friendly help I have received from John Urmston, the nephew of Jocelyn Brooke, in particular for granting permission to quote extensively from Brookes works and correspondence and for the touching photograph of Brookes mother and nurse at the gate of Ivy Cottage, which he took as a young man almost sixty years ago. Likewise I am grateful to Peter Waugh, the son of Alec Waugh, for permission to quote from his fathers work and the provision of amusing snippets of information.

I have been generously served too by the biographers of the minor subjects of this book Bob Gilbert who provided me with extracts from the diaries of A.E.Waite and helped me to locate The White Cottage; and Derek Wood who pointed me to the last letters of J.B.Reade and kindly supplied photographs. Without their work, both Waite and Reade would still be largely unknown. It was a delight to talk to the late James Troughton, the son of Lionel, the Kent cricket captain, who regaled me with stories of life in Bishopsbourne in the 1930s; and I am grateful too to Paul Tritton, the local journalist turned historian, whose book on A Canterbury Tale has proved a fascinating mine of information on the making of the film.

For permission to quote from copyright material and reproduce copyright images, I am greatly indebted to Dr Quentin Bone, Deborah Curle, Rachel Galloway, Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, and Desmond MacCarthy; also to Curtis Brown on behalf of Gillian Tindall, and the estate of Pamela Hansford Johnson; to David Higham Associates on behalf of the estates of Geoffrey Grigson, John Lehmann, Olivia Manning and Anthony Powell; and to Rogers, Coleridge and White on behalf of the estate of Cyril Connolly. I am also grateful to Harvard University Press for permission to quote extensively from the Folger Library Edition of the works of Richard Hooker (volumes I, II and V) and to the Trustees of the Joseph Conrad Estate for their general support. For access to papers and permission to quote from them, I have to thank the Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas and Washington University Library. Any copyright holders who have by chance been missed will, I hope, come forward in due time.

I am indebted to a number of archives and libraries for their usual efficient help, most particularly the Centre for Kentish Studies at Maidstone, Canterbury Cathedral Archives, Canterbury Local Studies Library and the London Library. I am similarly grateful to the Bodleian Library, Bridgeman Art Library, British Library, Canterbury City Council Museums, Corpus Christi College Library, Dorchester Reference Library, Marylebone Cricket Club Library, National Monuments Record, and Sturminster Newton Library.

For their individual help on specific aspects of the book I would like to thank Beryl Graham, Stephen Hardy, Howard Milton, Jane Reynolds, David Robertson, Georgina Troughton; and John Gilkes for yet another of his incomparable maps.

CLS

22 December 2009

It is an article of faith with me that a place consists of everything that has happened there; it is a reservoir of memories; and understanding those memories is not a trap but a liberation.

Adam Nicolson, Sissinghurst

In a book which tried to tell the story of a life it would be necessary to use not the two-dimensional psychology which we normally use but a quite different sort of three-dimensional psychology since memory by itself, when it introduces the past, unmodified, into the present the past just as it was at the moment when it was itself the present suppresses the mighty dimension of Time which is the dimension in which life is lived.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time

Memory: the past rewritten in the direction of feeling.

David Shields, Reality Hunger

CHAPTER 1

I am inspired by loyalty to place; loyalty to the narrow streets of Canterbury, the Christ Church Gate and the great Cathedral itself, standing in the green lawns of the Precincts. Above all Im inspired by gratitude and love for having been born a Man of Kent.

Michael Powell

The late summer of 1943 and a film camera is trundling along The Parade tracking a young actress through the bomb racked quarter of the city. The September sun climbs through the morning haze, setting fire to the tiny globules of dew hanging delicately from the purple spikes of rosebay willowherb, that flower of mystery scarce known in southern England for three hundred years but now brought back from the ashes courtesy of Adolf Hitler. She is walking purposefully in jodhpurs and jumper through a film set that could not be perfected even at Denham a twilight territory twixt town and country, where shoes strike pavements of urban urbanity while through the picket fence alongside stretch sunlit fields of fading summer flowers broken only by the archaeology of wartime destruction, the painful exposure of ancient cellars and what was once domestic privacy to the prurient public gaze.

On a corner she finds her bearings in the wasteland that was once Rose Lane, that haven of the medieval pilgrim where feet could be soaked and rested before crossing the final road to their destination at St Thomas shrine. The camera turns and pans the opposite side of St Georges Street to take in the southern aspect of the cathedral itself, another sight unseen by human eye for perhaps eight centuries, now that the ancient Longmarket and all the little crooked houses that once surrounded it lie wasted too in this sad field of general dereliction. The phalanx of mighty buttresses that bolster the south wall crouch alert on one knee in the morning sun, like a row of archers drawn up in readiness to launch destruction on the next wave of enemy to appear unheralded out of the clear, still, barrageballooned sky. The film company, now quietly revolutionising the English cinema, has its toxophilite associations too they have called themselves The Archers. The camera zooms in on the tower of Bell Harry standing in protective watch over this shattered remnant of the city, a symbol, like St Pauls, of the unshakeable power of collective faith that, unlike mere bricks and mortar, cannot be torn that easily to the ground. The cathedral now on camera waits to dispense its blessings upon a new set of modernday celluloid pilgrims the American soldier seeking news of his lost fiance, the young materialist who longs to play a cathedral organ, and the hapless landgirl (the figure now walking the bombsites) mourning her lover posted missing.

Next page