As the time comes to launch Stallside Manner, it is appropriate to recognize the people who have helped bring it into existence. As with Don't Turn Your Back in the Barn, the input from my production team has been outstanding.

Betsy Brierley, my editor, has expended the tireless energy that I have come to expect from her. How fortunate I was to find a person to work with who understands my vision and my writing style. Wendy Liddle has again added her own delightful flavour to my book through her illustrations. She has been a cheerleader from the sidelines since the first chapters were in their infancy. Warren Clark has wielded his considerable skills to create an appealing book design for Stallside Manner.

My "in-house readers" have provided an invaluable service by previewing the manuscript to help me expand and clarify the stories for my audience. Thank you Nancy Wise, Pat Badger, Al Theede, Bob and Marian Moats, and Jack Ingram.

I want to express my sincere appreciation to those who read Don't Turn Your Back in the Barn and sent me letters and e-mail messages of encouragement. Many times in the past months, your words buoyed my spirits and motivated me to go on.

I extend a special thank you to all those people who have come forward with photographs and reminders of our past association. Many of your stories are in this book; others will come to life in future collections. Please continue to send me your reminiscences. They will help to keep the stories flowing.

Throughout the writing of this manuscript, my family has encouraged me and steadfastly accepted the inevitable disruptions. Thank you Ruth, Joan, Marshall, Gordon, and Alicia.

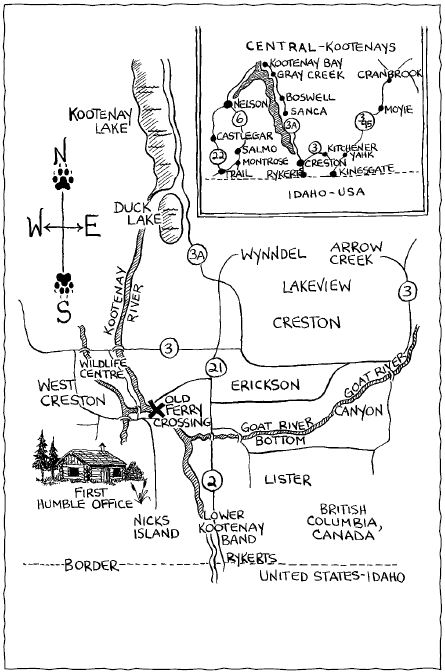

I pulled over to the side of the road and glared at the scratches on my notepad. Damn! Why hadn't I looked at the odometer when I left Wynndel? I had been to Tilly Hubner's farm several times during the previous summer, and I should have recognized her exit but, along this twisted highway, they all looked similar. The directions said four miles past the storeI was sure I should have come to the turnoff by now. I stared over my shoulder with the certainty that I had driven past it.

Gravel-laden mounds of snow lined the ditches at the sides of the road. Although most of Highway 3A was skirted by a green hedge of fir and pine, here birch and cottonwood persisted, their limbs still bare and lifeless. It would be a few months before tourists crowded this scenic route to the Kootenay Lake ferry. A car rounded the corner behind me, slowed, then proceeded past.

I put the Volkswagen in low gear and eased back onto the highway. Lug whined and twirled around on the seat. Certain that something exciting was in the making, he rooted at my hand as it rested on the gearshift.

"Settle down, you big boob...We're lost again."

I accelerated. If I didn't find the place in the next few minutes, I'd turn back and figure out where I'd messed up. I had rounded several sharp curves in succession and was looking for a place to turn around when I recognized the access up a steep hill to the right.

"Well, look at that, boy. There it is."

Although I couldn't see Tilly's house, I could picture the tall, stark building at the top of the drive, its bunker-like garage plunked in front, as if dropped by a giant bird, its massive concrete walls and roof so out of touch with the rest of the building and the surrounding landscape.

Tilly existed in that barren little house as if the Depression had never ended, and even having a cup of tea with her made me feel guilty. Her cupboards were always bare, her ancient refrigerator empty except for a lonely can of evaporated milk. There was hardly a stick of furniture or a picture on the wall; one would wonder if she had occupied the building only yesterday. It was as if her possessions were in storage somewhere, waiting for the day she would move in and start living there.

I rounded the corner to her pasture access. There she stood, a bucket of water on either side of her, her long, lean body straight, tall, immobile, looking like some classical figure carved from stone. She held up her hand and shook her head as I pulled to the left and parked in front of her.

"You better stop right here, Dave. You'll never get out of the driveway this time of year. It's slick as can be, and there's no place to turn around."

Lug planted his front feet on my lap and strained to get a better look. Whining excitedly, he skidded his nose across the side window, leaving a streak of slime glistening on its surface.

"You'll have to carry your stuff from here," said Tilly.

I shut off the engine and opened the door. Lug tried to muscle his way out, but I caught him as he stepped down. "Stay!"

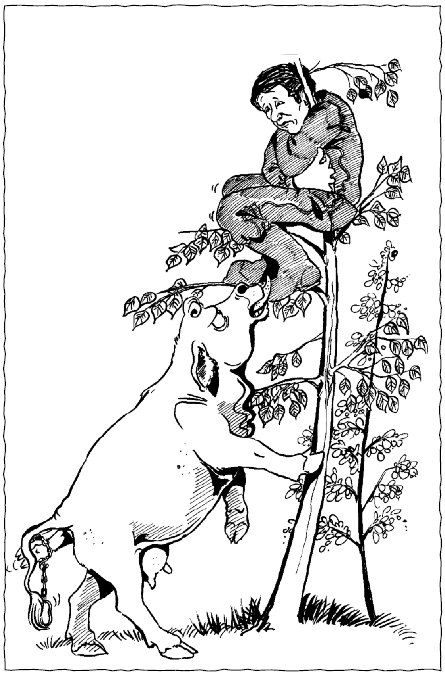

"God, you have no idea how I hated to call you out here for this cow. She's such a pain with strangers."

"She's not the big blond one that put me out of the corral when we were vaccinating them last fall, the one that knocked Joe Pogany's horse out from under him during community pasture roundup?"

"Afraid so...and she'll be even worse now that she's this close to calving. Maternal instincts bring out the worst in my girls. Every other year, I've been lucky and she's delivered on her own. I just threw out feed and stayed as far away from her as I possibly could. She doesn't have much use for me either! I suspected she was going to calve soon and was lucky enough to lure her into the corral last night."

I rummaged in the back of the car, unloading the calving jack and stuffing chains and handles into my pockets. I grabbed my bucket, threw in the container of soap, and draped the lariat over my shoulder. I felt a sudden urge to drag my feet, but Tilly was not about to let me dawdle. With a bucket in either hand, she headed down the trail. I slammed the end door shut and took off after her. She was already several strides ahead of me, her long legs motoring deftly down the steep incline towards Duck Lake below us.

"With your being all alone like this, Tilly, the place for a cow like her is in the deep freeze. If she knocked you down and hurt you when you were all by yourself, who'd ever know you were even out here?"

"I can look after myself. I worked a long time to be able to sell an animal as a purebred. When we're done with her, I'll show you her last year's calf. He's one fine-looking bull."

"Sure hope he doesn't have his mother's temperament."

Tilly stopped and looked at me as if I had stabbed her in the side. Even the slightest criticism of her cattle, or of the Charolais breed in general, was known to summon a tirade in their defence. She hesitated for a moment, ready to give me a piece of her mind, then sighed and strode off. This was a time like no other in the North American beef industry. Prices for cattle in 1974 were good, and the introduction of exotic breeds like Charolais and Simmental was sending people clamouring to import purebred stock.