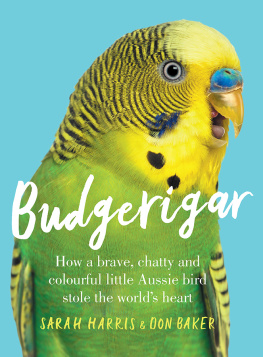

First published in 2020

Copyright Sarah Harris and Don Baker 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 548 0

eISBN 978 1 76087 381 3

Illustrations by Mika Tabata

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover Design: Design by Committee

Cover image: Alarmy Images

For our brothers Phil and Tim, and also Miss Lucie

SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL sat up in his bed, ubiquitous unlit cigar hanging fatly from his lip and a small blue-green bird perched atop his head, and dictated to his secretary. Between occasional swooping sips of his masters whisky and soda, Toby the budgie dropped his own little bombs on the top-secret thermonuclear project documents spread across the British prime ministers counterpane. Defence minister Harold Macmillan recalled the scene in his diary entry for 26 January 1955: this little bird flew around the room, perched on my shoulder and pecked (or kissed my cheek) while sonorous sentences were rolling out of the maestros mouth on the most terrible and destructive engine of mass warfare yet known to mankind. The bird says a few words in a husky voice like an American actress.

At age eleven, Richard Bransons first enterprisegrowing Christmas treeswas nibbled into non-existence by rabbits. Undeterred, he and best mate Nik Powell hit on a scheme to become budgie barons, with Richard convincing his father to build a large aviary on the familys Surrey property. But the budgies established themselves rather too successfully. Even after everyone in Shamley Green had bought at least two, we were still left with an aviary full of them, the music, technology and transport magnate recalled in his autobiography Losing My Virginity. Not long after the boys returned to boarding school, Richard received a letter from his mother lamenting that rats had invaded the aviary and eaten all the budgies. It was many years before she admitted she had actually left the door open and theyd all escaped.

In the late 1920s, the Japanese nobility, led by Emperor Hirohito, ignited an extraordinary boom in the budgerigar market when the birds became popular as betrothal gifts from families of wealthy grooms to their brides-to-be. Hirohito, a student of natural history, had been enchanted by budgerigars on a 1921 visit to Europe before his ascension to the Chrysanthemum Throne. He later said it had been during this trip that I, who had been a bird in a cage, first experienced freedom. In 1927 a member of the Imperial household paid the princely sum of 175 (the equivalent of more than $13,000 today) for a single blue budgie. But when there was a global outbreak of psittacosis (parrot fever) in 192930, the market crashed and for a time the international trade in budgerigars was embargoed.

IT IS GENERALLY supposed that the budgie didnt make it onto the ark of dead things Captain James Cook took back to England with him in 1771 after his voyage of discovery to find Terra Australis. But that was not for want of trying by the feverish naturalists who had accompanied him.

Any creature within their sights became fair gamequite literally. The natural history artist Sydney Parkinson described the Endeavours entry into Botany Bay thus: [There were] a great number of birds of a beautiful plumage; among which were two sorts of parroquets, and a beautiful loriquet: we shot a few of them, which we made into a pie, and they ate very well. We also met with a black bird, very much like our crow, and shot some of them too, which also tasted agreeably.

But while he observed, and indeed ate, any number of birds, Parkinson only actually drew one of them. This reflects the expeditions extreme bias towards botany, a bias shared by its chief scientist Joseph Banks, who later enthused to his aristocratic French friend and chemist, the Comte de Lauraguais: The Number of Natural productions discoverd in this Voyage is incredible: about 1000 Species of Plants that have not been at all describd by any Botanical author. The 500 fish, as many Birds, and insects [of the] Sea & Land innumerable were very much also-rans.

While Banks scrupulously kept and catalogued the botanical material hed gathered in New Holland, the zoological specimens were poorly preserved and never fully catalogued, and were ultimately scattered among collectors, museums and societies. Many of the avian specimens were simply skins or pelts with heads; the rest of the bird had been consumed or thrown away because, in order to be pickled in jars, they would have required more spirit [alcohol] than we could afford.

Frankly, a budgerigar could have stowed itself aboard the Endeavour and chattered under the great botanists nose, but he would still have paid more attention to a piece of antipodean bracken. The best a budgie might have hoped for was that Banks would eat it.

The Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander accompanied Banks on the Endeavour, and in 1782 he dropped dead of a brain haemorrhage in Bankss house while logging species discovered in the Pacific. The relationship between events may not have been entirely coincidental. That the task remained unfinished only added to the chaos of the Banks collection. In addition to material collected on the first Cook voyage, Banks, one of the eighteenth centurys foremost men of science, was the recipient of many thousands of specimens sent by expeditioners and colonists around the worldfirst to his Mayfair home and, after 1777, to more commodious premises in Soho Square.

Reverend William Sheffield, as the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, oversaw a none-too-shabby collection that featured the death mask of Oliver Cromwell, the Kish tablet (inscribed with some of the earliest cuneiform/pictographic writing of the ancient Sumerian people) and the very lantern Guy Fawkes carried when he was arrested underneath the Houses of Parliament on that November night in 1605. Yet nothing could prepare him for his visit to Banks at the botanists New Burlington Street home the year after he returned from Australia.

The good reverend could barely contain himself when recounting his excursion in a letter to fellow parsonnaturalist and ornithologist Gilbert White on 2 December 1772:

It would be absurd to attempt a particular description of what I saw there; it would be attempting to describe within the compass of a letter what can only be done in several folio volumes. His house is a perfect museum; every room contains inestimable treasure. I passed almost a whole day there in the utmost astonishment, could scarce credit my senses. Had I not been an eye-witness of this immense magazine of curiosities, I could not have thought it possible for him to have made a twentieth part of the collection.

Sheffield found the third room he entered the most breathtaking: This room contains an almost numberless collection of animals; quadrupeds, birds, fish, amphibia, reptiles, insects and vermes [worms], preserved in spirits, most of them new and nondescript. Here I was in most amazement and cannot attempt any particular description.

Next page