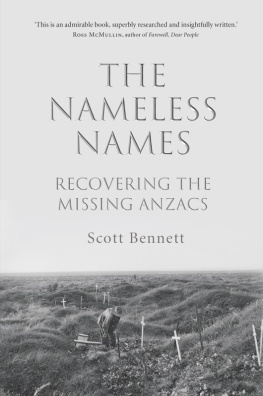

THE NAMELESS NAMES

Scott Bennett was born in Bairnsdale, Victoria, in 1966. He gained an Executive Master of Business Administration degree from the Australian Graduate School of Management at the University of Sydney, and has worked for many of Australias most recognised retail companies as a management consultant or an executive manager. In 2003, he visited the Great War battlefields in France and Belgium to retrace the steps of his great-uncles, who had fought there. This experience led him to question the many truths that have developed around the Anzac legend. The result was the writing of The Nameless Names and his first book, Pozires , which re-examined the battle of Pozires.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave., Suite 100, Minneapolis Minnesota, 55409 USA

First published by Scribe 2018

Copyright Scott Bennett 2018

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

9781925713558 (Hardback edition)

9781925693317 (e-book)

A CiP entry for this title is available from the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

To Pablo

Contents

Ive seen a battalion in the dust on the road, a third of them for death or worse and no special marks on them, the dust for all.

Ernest Hemingway

Information

Conversions

1 inch 2.54 centimetres

1 foot 0.3 metres

1 yard 0.91 metres

1 mile 1.6 kilometres

1 acre 0.4 hectares

Formations in the British Expeditionary Force

Body Commanded by Approximate Infantry Number

Army General 100,000 to 150,000

Corps Lieutenant-General 50,000

Division Major-General 12,000

Brigade Brigadier-General 4,000

Battalion Lieutenant-Colonel 1,000

Company Captain 250

Platoon Second-Lieutenant 60

Section Lance-Corporal 15

Introduction

The people have asked for houses and we have given them stones.

William Richard Lethaby

C olumns of soldiers tramp the mud-smeared Ypres Road. The stamp of their sodden boots upon the cobblestones sounds a drumbeat. They tramp past the gaunt ruins of the medieval Cloth Hall and through the humps of broken masonry that once formed the Menin Gate. The drumbeat fall of their boots continues uninterrupted every hour, every day, and every night for four long years. A mile beyond the Menin Gate is Hellfire Corner, and a mile further is the abyss. In that sodden wasteland, cannons sound, machine guns stutter, parachute flares fizz, poisonous gas drifts, and disembowelled horses shriek. Five thousand men die every month; 5,000 are crippled every week. A quarter-of-a-million stout-hearted men dissolve into ghosts, shadows, and memories. There is no single yard of ground that does not cost blood and bone. This is the Ypres Salient, the ten-by-six mile shell-torn expanse of Belgium that the British and German armies bitterly contest throughout the Great War.

A century later, I walk the patterned cobblestones of Ypres Road. Quaint shops that display Belgian chocolates and fine pastries have replaced rubble-lined streets. The tourists who collect inside these premises to admire the ornate window displays and swap cheerful banter have replaced the columns of tramping soldiers. Yet the residue of war remains. As I walk further, the shops abruptly end and are replaced by a colossal arch that straddles the street. Its straight lines and geometrically precise angles cast a mournful shadow across the Ypres-to-Menin road. The inscription on its faade reveals itself: To the armies of the British Empire who stood here from 1914 to 1918 and to those of their dead that have no known grave.

I have reached the haunting Menin Gate Memorial.

I enter the archs belly to shelter from the menacing clouds that threaten rain. Tourists wearing long overcoats, with collars upturned, mill at the memorials base. Soon the traffic will stop, and buglers will sound the Last Post. It is a ritual that has continued uninterrupted every evening and in all weathers since 1929.

Standing among the sodden wreaths and faded flowers, I see the inscriptions etched on its Portland stone walls: panel after panel, floor to ceiling, with the names of 55,000 Indians, Englishmen, Australians, Irishman, Scots, and Canadians. Each name is inscribed with uniform precision: letters evenly spaced, justified to the right, in an artless Roman typeface.

I struggle to comprehend how tens of thousands of souls could be lost in the Ypres Salient, just a few miles beyond the brightly lit shops, and how their existence could be distilled down to names on endless lists. And I find it difficult to discern an individual name from those lists. Perhaps thats the way Sir Reginald Blomfield, the architect of the Menin Gate Memorial, intended it: no individual name should be distinguished from the masses; a visitors gaze should never penetrate the endless lists. Yet I find myself compelled to do just that. To understand what this memorial really symbolises, I must pierce Blomfields dehumanising illusion, and put a story to a name to draw out warmth, love, and grief from the cold stone.

I gaze upon a single panel. Battalions dissolve into individuals: Albert, Allan, Allen, Allen J. Josiah Allen. I reach out and sweep my hand across Josiahs name, my fingertips catching on the edges of each letter. I punch Josiahs name into my iPhone, and discover that he was a 27-year-old grazier from the remote town of Gin Gin in Queensland who enlisted in July 1916. I learn later that Josiah was a clean-living bloke who was a member of the local temperance movement and a devout churchgoer who attended the Gin Gin Methodist Church. Josiah was recognised throughout the district as an expert horseman capable of riding the wildest stallion bareback, and considered an expert marksman capable of shooting out a flys eye at 500 yards.

I ponder what Josiah may have thought in June 1917 as he marched past where I now stand. Did he realise that his battalion would be thrust into the bloody offensive at Messines Ridge? Was he comforted that his brothers, Ned and Ernest, marched alongside him? Within days, a shell burst would kill Josiah, his remains would lie buried forever somewhere on the mired battlefield, and his name would be memorialised on the Menin Gate.

Josiah suffered the ignominy of being lost in the Flanders mud, along with thousands of others. Ironically, in commemoration, he suffers the same fate lost in a sea of tens of thousands of uniform inscriptions. Memorials to the Missing are not about people, reflected Geoff Dyer, the author of The Missing of the Somme , they are about names: the nameless names. Yet, with some rudimentary research, I uncovered Josiahs story. I have penetrated the memorials endless lists and grasped the impost of a single name. I understand Josiahs 12-month journey to Messines Ridge, his aspiration to return to sunny old Gin Gin, and his familys grief when he was listed as missing. What other intimate stories can be drawn out from those lists?

Blomfields method of commemorating the British Empires missing the so-called imperial framework is replicated right across the Great War battlefields. A short distance from Ypres, among ploughed fields, is the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing: the uniform stone-and-flint panels that rim the cemetery list 35,000 missing British and New Zealand soldiers. In northern France, on the Somme, the identity of 74,000 British soldiers is etched on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing. Across almost 1,000 commonwealth cemeteries that trace the Western Front, 180,000 near-identical headstones simply read A Soldier of The Great War Known Unto God.

Next page