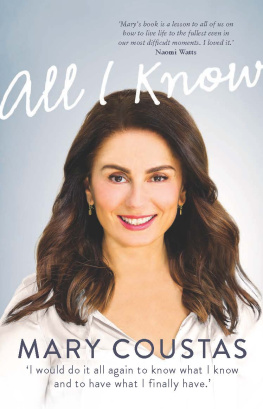

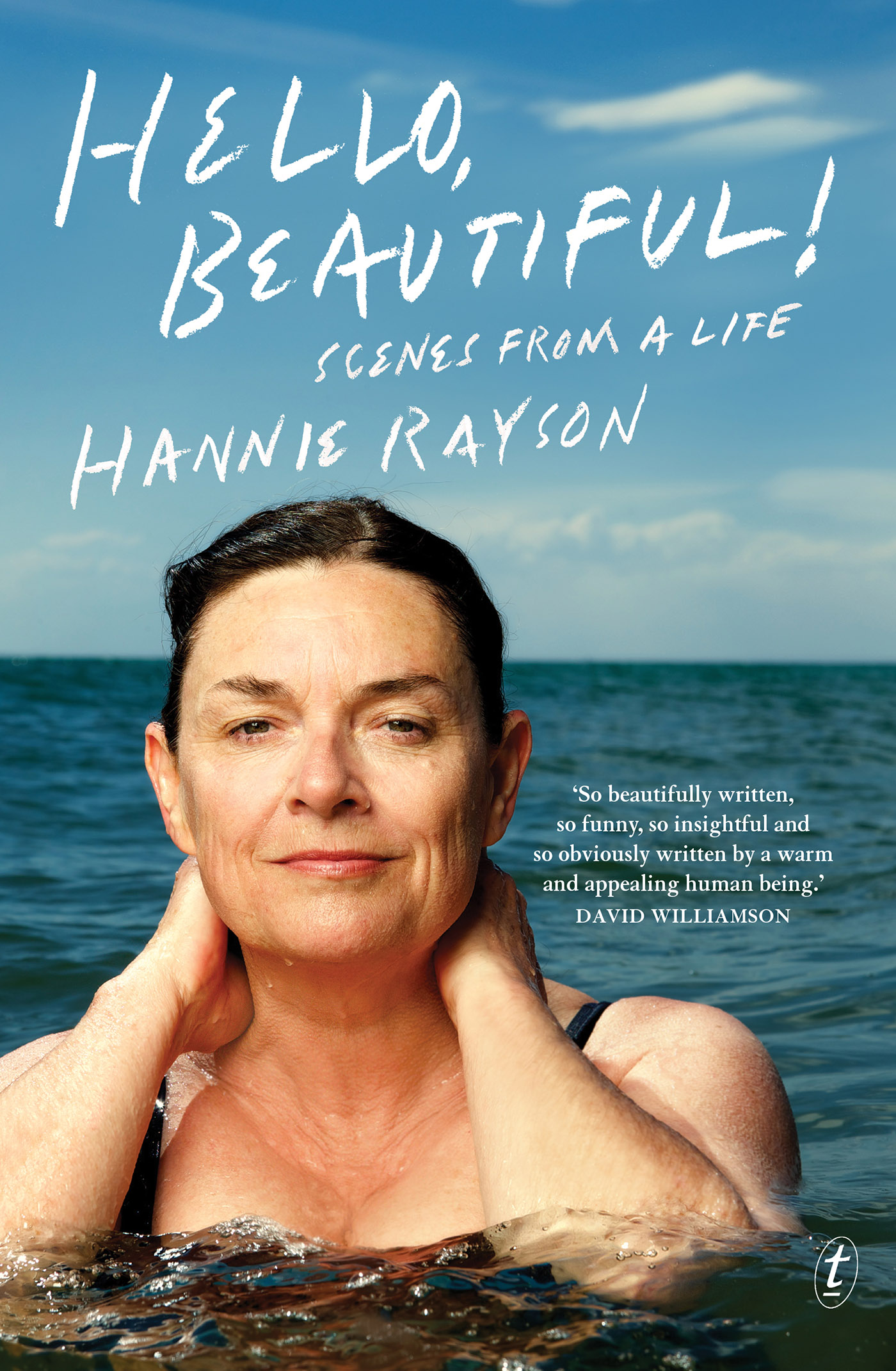

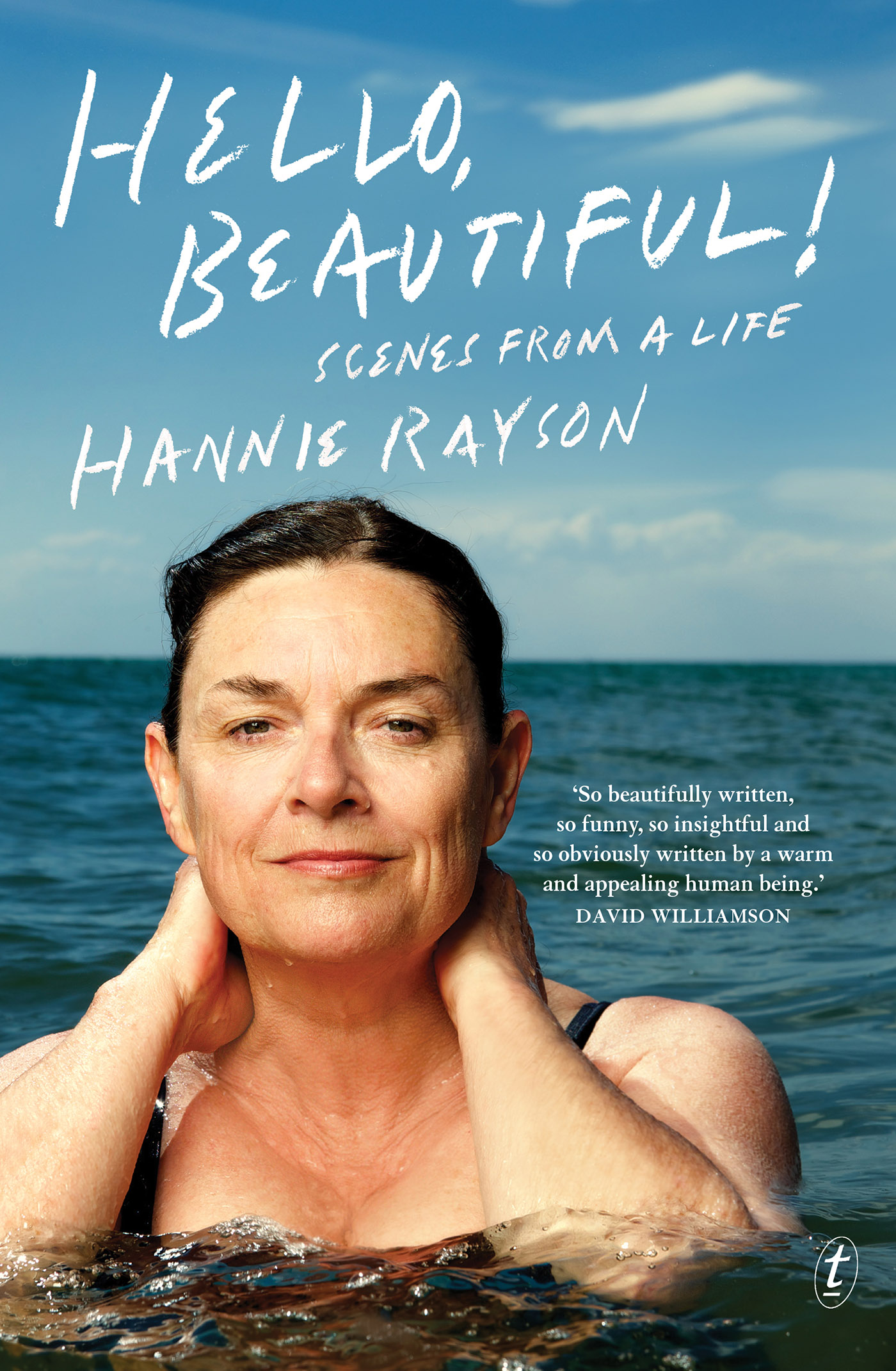

I AM indebted to Hilary Glow and Amanda Smith for suggesting I write this book. Onehorrible winters night, I sobbed my way through the sushi and sashimi combo at mylocal Japanese. I was miserable: the Melbourne Theatre Company had just knocked backmy most recent play.

Instead of saying, It will be all fine, which is the usual way you might consolea sobbing woman in a public place, my oldest friends said, Forget theatre. Writea book. Wed buy it. Wouldnt we?

So, that night, emboldened by an in-principle pledge of $32.99, I sent three storiesto Michael Heyward at Text Publishing. He rang the next morning to offer me a bookdeal.

The rest is a story of pure happiness.

Michael nurtured this book with grace and enthusiasm, aided by Alaina Gougoulis,the editor from heaven. Jane Novak has been similarly encouraging and lovely.

Three of my writing friends, Charlotte Wood, Caroline Baum and Ailsa Piper, havewritten to me at least twice a week. Dear Girly Whirlsthis correspondence has sustainedme for the entire time Ive been working on this book. Every writer needs a girlywhirl to fill her sails, and send wise counsel, when, out at sea, her boat startsto fill with water.

My mother and my son, who feature in these pages, have been generous and graciousin their powerlessness.

Finally my love and thanks to Michael Cathcart, my husband. Any woman should be solucky.

I WAS born in Brighton. Some people call it Brarton. Others call itthe horrorBayside.Brighton is about twenty minutes by train from the centre of Melbourne on the Sandringhamline. It sits on six kilometres of foreshore on Port Phillip Bay. It has historicsea baths, where we learned to swim, iconic bathing boxes on Dendy Street beach,great wealth and Shane Warne.

My husband, Michael Cathcart, says, Hannie grew up in Middle Brightoninsulatedfrom the rest of the world by all the other types of Brighton. But he is so verywrong. Our house was in East Brighton and people in East Brighton were different.Back then, in the 1960s.

These days, the women double-park their SUVs and dash between school drop-offs, thegym and the gourmet deli. They are the yummy mummies, with designer toddlers andtoy dogs (spoodles, groodles or cavoodles), shopping in Church Street in their post-workoutactive wear from a sportswear shop with a sign out the front that reads:

Run Girl Run!

Run like Ryan Gosling is waiting for you at the finish line.

Go get him girl!

They have coffee dates at the Cosmopolitan Place, which is the least cosmopolitanplace imaginable. It specialises in sandwiches and Devonshire teas. There is a dressshop called Sweet and Vicious. Another one along the street is called Very Very.

I ask my son, Very, very what, do you reckon?

Very, very white, he says, rolling his inner-city eyes.

Outside a salon dedicated to blow-drying hair (you can have a blow-dry party forsixty dollars a head) there is a poodle in a car with its paws on the steering wheel.

Look! I say to my son. Even the poodles drive BMWs.

Our family left Brighton in the mid-seventies. We scraped it off our shoes and noneof us have set foot in it again. That is, until last week, when I got in my car anddrove down the Nepean Highway to have a look at my old house.

Its 1962. We live in Robinson Street on the corner of Parker. My parents have christenedme Helen but I cant get my tongue around it. Helen Rayson. I call myself Hanna Basin.My version sticks. I become Hannie.

We are not wealthy. We have only one servant: our mother. She makes our beds, washesour clothes and sews on our missing buttons. My dad sells real estate. One nightat dinner he tells us hes sold a house to a lady who says hes the most handsomereal-estate agent in Brighton. We gag on our crumbed cutlets.

My mum loves my brothers and me to bits, and never whinges about having to do housework.There is no permission, at this stage, for a housewife to feel trapped. The Americanfeminist Betty Friedan has not yet published The Feminine Mystique: the world hasyet to hear about the problem which has no name.

In Brighton, we have a more pressing problem, and his name is Harry Smith.

Once a fortnight, on a Monday, Harry pulls up in his pale-blue Hillman Minx. I watchhim from high up in the massive cottonwood tree out the front of our house. I amfive years old, wearing my brown stretch pants and green jumper that I have chosenfrom Straws Drapery specifically for camouflage and detective work. I spend a lotof time in trees.

Harry makes a dash up our path, bent over as if hes been caught in a sudden downpour.He is clutching a ledger and a leather bag to collect the rent money for Sir GilbertDyett, who owns our house. Sir Gilbert is the president of the RSL and has a considerableportfolio of investment properties, houses he built after the war. He lets thesehouses cheaply to ex-servicemen. Wally and Maur next door have got one. Mac and Belle,over the road. The Keens. And Ralph and Little Lynnie.

On many occasions when Harry Smith knocks, my mum will have to hide in the hall cupboardbecause we dont have the money. My mother doesnt hide because Harry is a mobsterwho will cut off her little fingerHarry is a short fellow with a comb-over who liveswith his motherbut because she is ashamed of being skint. However fair and decentSir Gilbert may be about his rental policy, if you havent got the money, what canyou do? You keep quiet, never suspecting that all your neighbours are in the sameboat.

On Sundays, Sir Gilbert strolls down our street wearing a black hat and black coat,surveying his estate and patting small children on the head. I was never patted.

When my parents arrived at Robinson Street, there were market gardens behind theback fence. Gradually, my father added sleep-outs and extra rooms to our place, andnew houses sprang up around us. First there was Major Darcy next door. Then Bettyand Alan moved in with their kids.

Then Di and John, who nip over to our house for fondue parties on a Saturday night.These gatherings involve frying cubes of meat into brown frizzled lumps, and dancingto Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. My dad loves parties. The whole side of ourhouse is lined with empties: brown beer bottles waiting for the bottle-o to comeand load up his truck. He hands over cash in exchange for empty bottleswhich Mumfinds embarrassing, but handy.

My brothers are students at the high school at the end of our street. My oldest brotheris involved in school drama: he is the lighting and sound man. We host large castparties after his plays. Mum lets the kids drink beer from jam jars after we runout of glasses and cups.

No one worries about gatecrashers or hooligans. The only person displaying antisocialbehaviour is me. I am vomiting. I am eleven, and my brothers eighteen-year-old friendgives me a small glass of crme de menthe and asks me to marry him. I have been schooledin not hurting peoples feelings, but am sick with anxiety about having to say yes.It never occurs to me that he might be joking.

Two houses down, Hilda and Harry Keen keep three malevolent pekingese. They aresmall and they know how to hate. My dog hates them back. When we walk past the Keenshouse, the pekingese run back and forth behind the wire fence, yapping and slatheringand smacking into each other. My dog bounds up and down, shamelessly flaunting herfreedom. She thinks those pekingese are schmucks. I wonder why Hilda keeps them,what pleasure there could possibly be in patting them and peering into their dark,disgruntled souls.

By any measure, Hilda and Harry should be riding high, as they are the ones who bringglamour to our street. They have a daughter, Janis, and she is the closest anyonein Robinson Street has ever come to celebrity. She is in the Channel Nine dancers.She wears an Alice band and has perfect white hair turned up at the bottom like PattyDuke.

Next page