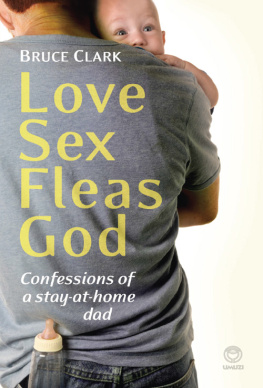

This book is dedicated to my literary agents, Lesley Pollinger and Tim Bates; to my theatrical agents, Phil Belfield and Mark Ward; to my editor Toby Buchan, and to my publisher, John Blake. Between them they gave me the time, opportunity and encouragement to finish this book, which began over lunch when I asked off-handedly how is it possible for a barnacle to make love. This book is the result of that investigation.

B. M.

Ah, yes.

T his is not an academic book. In the words of the great French entomologist, Jean-Henri Fabre (18231915), Others have reproached me with my style, which has not the solemnity, nay, better, the dryness of the schools.

Im sure that serious researchers into animal behaviour will be frustrated by the scarcity of Latin words to describe the biological processes. Ive had to use a few because there is no other way to describe certain things. The more obscure words have been given dictionary definitions in the alphabetical index. Perhaps these pages will inspire some curious mind to take a deeper look into these matters and gain fresh insight. The sketch notes that follow are written mainly for laymen like myself.

I absorb interesting trivia like a sponge so, with luck, some of you will share my fascination for curious, extraneous detail.

The seeds of this book germinated when I had one of those random thoughts that strike us all on occasions how on earth do barnacles breed? They are underwater for the most part, stuck to the bottom of a boats hull for their entire life, not daring to move, so how do they propagate? (The answer, by the way, is under Chapter B.) Once I had solved the barnacle mystery, my mind wandered further afield. For example, since the primary purpose of sex is to propagate whichever species we belong to, why does a chicken waste her entire life laying unfertilised eggs? (The answer to that is under Chapter C.)

Evolutionary design is blind. All embryos look like fish in the early stages. Why? A billion years ago, the sea reduced in depth, revealing dry land. Some of our ancestors had little choice but to venture onto that inhospitable land and try to survive on it. Animals still start off as fish in the womb before adding and subtracting those bits and pieces that evolution has wrought during an unimaginable length of time. So, in effect, this book has taken millions of years to write.

It seems that in nature nothing happens for a reason. It just happens. Essentially, all animals are the same. Its the differences that make it interesting.

As the French say with saucy insouciance, Vive la diffrence!

(Footnote: some of the books to which I owe my research are listed in the Epilogue.)

B RUCE M ONTAGUE

Hove, 2014

AARDVARK

The aardvark is a nocturnal animal found in sub-Saharan Africa. It has no known relatives, and like the Red Panda (see Red Pandas), is the only living species in its order.

Aardvark means earth pig. However it is not remotely related to pigs. To look at, it resembles a bald, hunchbacked rat with the snout of an anteater, but neither is it a rat nor a true anteater. It is not even related to the South American anteater that it superficially resembles. Its unlikely distant cousin, several times removed, is the elephant. Not a kissing cousin though. At full stretch, an aardvark can achieve a length of 6ft, two-thirds of which is tail.

Its big ears move independently, like those of a kangaroo. And if theres a dusty atmosphere, it can somehow button down its ears to keep them clean. It has 20 teeth without enamel or roots called tubulidentata, meaning tube-toothed, which continually regenerate themselves.

The male has a scent gland situated near his testes that emits a strong musky smell. The female has a gland near her vulva, which will emit the appropriate pheromones when her time is ripe.

A shy fellow, the male aardvark only reveals his penis when he is ready for penetrative sex. At this juncture, his penis springs from the prepuce (a layer of skin protecting and concealing the sex organs) and rapidly acquires tumescence. In the Congo, he will mate with many female aardvarks as often as possible between April and May. The gestation period is seven months.

Aardvarks are solitary animals with long extensile tongues and spend their days sleeping deep down in burrows. Their gastronomic delight consists chiefly of termites, though not to the exclusion of other hymenoptera that happen to cross their path. (Hymenoptera is the scientific word for a large order of insects that includes bees, wasps, ants, and sawflies.)

The aardvark is not averse to asserting squatters rights in old termite nests when ready to give birth. The time of oestrus (the period when most female mammals, except humans, are receptive to sexual activity during which ovulation occurs, commonly called on heat) is evident when the area surrounding the females vagina swells up.

The mother gives birth to a single offspring each season. A baby aardvark weighs less than 4.4lb (2kg) and has smooth pink skin. This little fellow spends his first two weeks in the burrow with his mother, and once he has gained his land legs he will accompany her on nocturnal feeding forays. After 16 weeks, he is completely weaned and at the age of six months he wanders off for a life on his own. Aardvarks have a life span of 10 years in the wild, but can survive twice as long in captivity.

ALBATROSS

The word albatross derives from the Arabic language and means the diver. The original word described any number of diving birds, including herons. Alcatraz, the island off San Francisco, derives its name from the same root. They were originally called gooney birds and sometimes mollymawks.

When Captain Cook was sailing through Antarctica he came across an island crammed with macaroni penguins, petrels, prions, shearwaters, fulmars and albatrosses. He called it Bird Island. Despite the summers being wet and windy, many birds, including albatrosses, use it as a nesting site. They come here every couple of years to mate and lay an egg. It is possible that their life expectancy could extend to 100 years.

With an 11-ft wing span (340cm), they spend their days cruising over the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific searching for food. They cover almost 1000km every day. Uniquely, they have pipe-like tubes either side of their beaks that act in the same way as pitot tubes on aeroplanes (pitot tubes measure wind velocity). These enable them to judge their airspeed. Albatrosses fly so effortlessly that their heart rate is practically the same when cruising on the thermals as it is at rest. They have the ability to shut down their brain compartmentally, allowing them to fly on auto-pilot so that they can sleep on the wing.