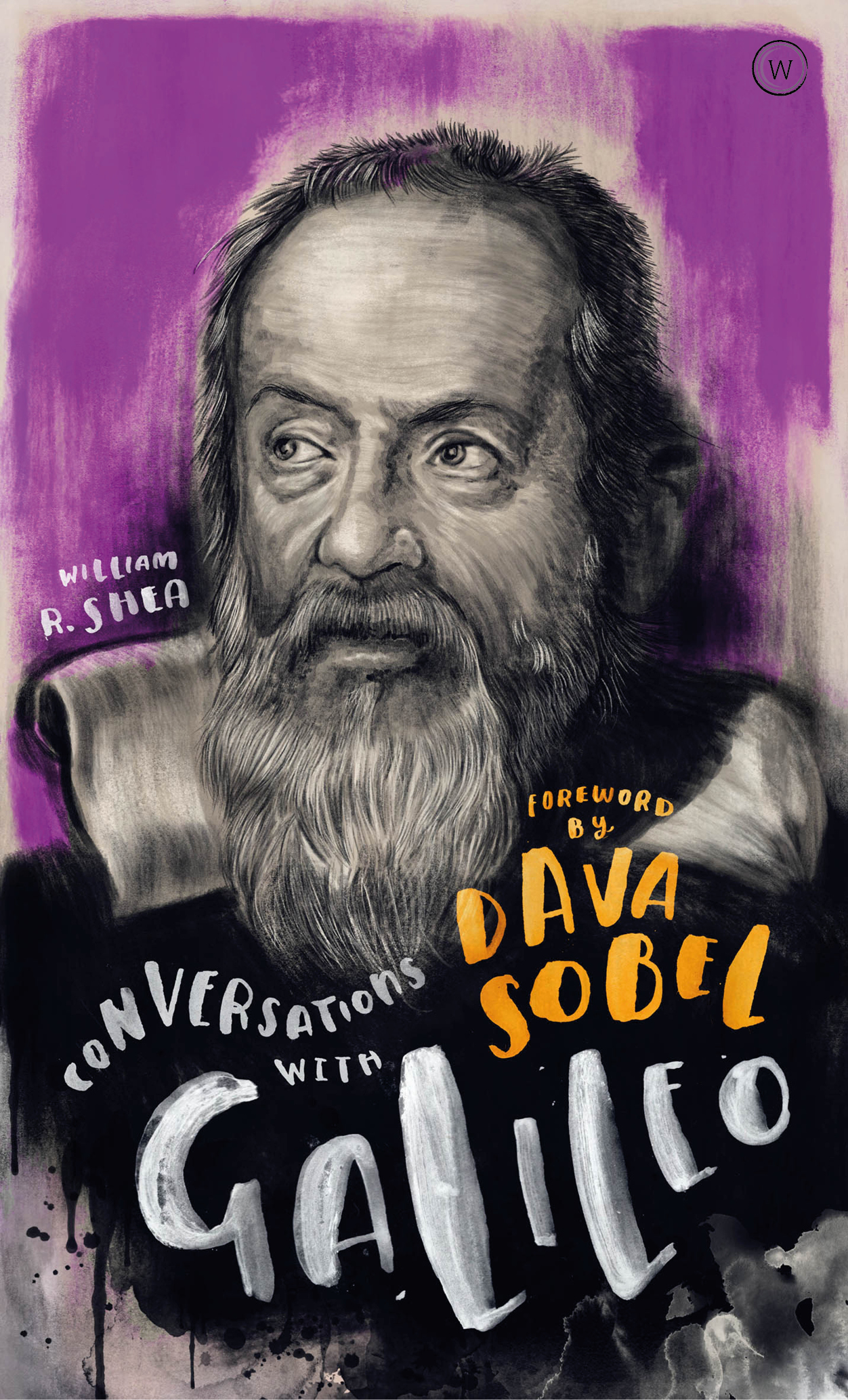

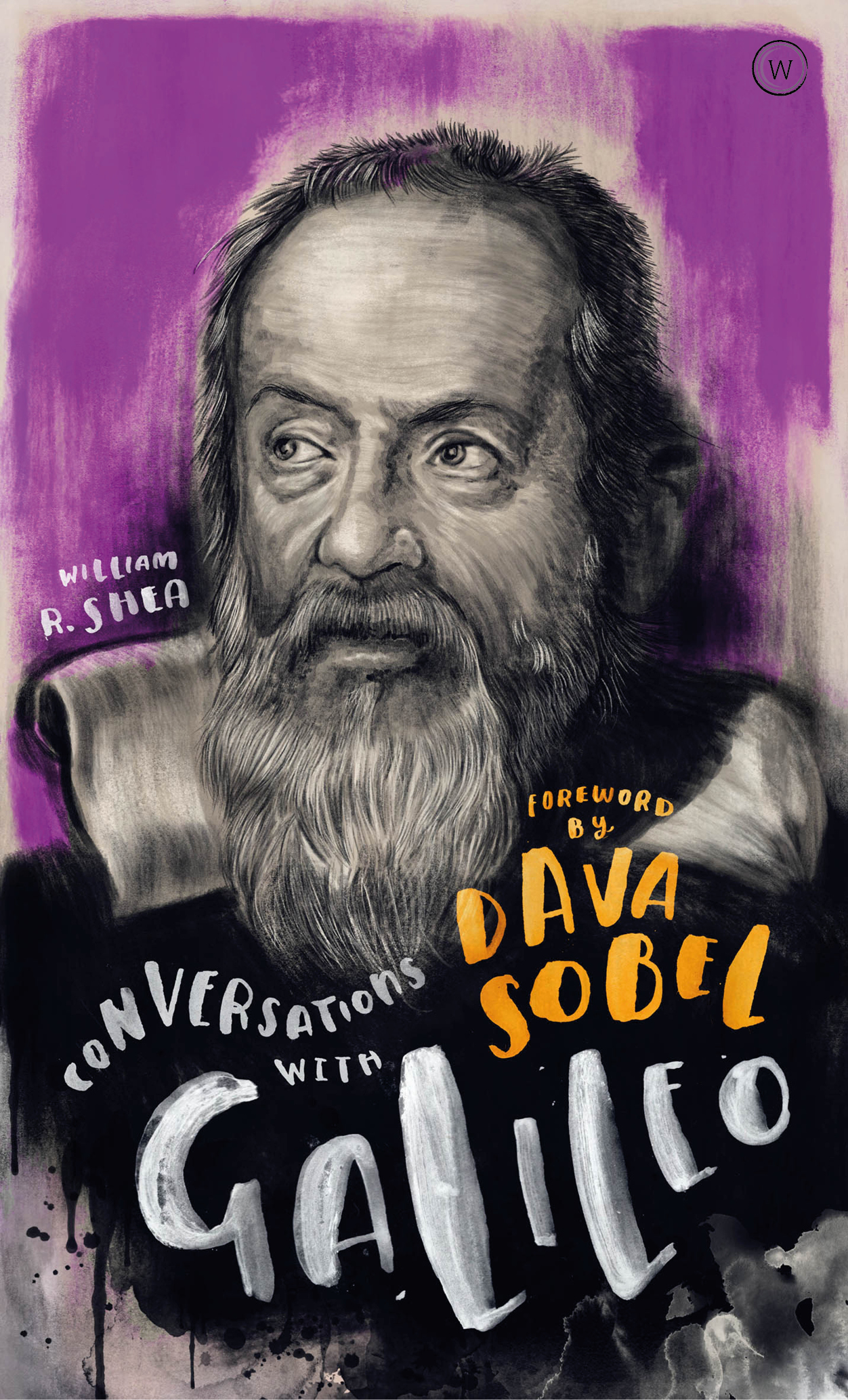

Originally published under the title Coffee with Galileo 2009

This edition first published in the UK and USA 2019 by

Watkins, an imprint of Watkins Media Limited

Unit 11, Shepperton House

8993 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

Design and typography copyright Watkins Media Limited 2019

Text copyright William Shea 2009, 2019

Foreword copyright Dava Sobel 2009, 2019

William Shea has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the Publishers.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by JCS Publishing Services Ltd

Printed and bound by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78678-249-6

www.watkinspublishing.com

William R. Shea is Galileo Professor of the History of Science at the University of Padua, Italy. He has written several books on Galileo and the Scientific Revolution. The latest, written with the Spanish scholar Mariano Artigas, are Galileo in Rome: The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius (2003) and Galileo Observed: Science and the Politics of Belief (2006).

Dava Sobel is an award-winning and bestselling writer of books on the history of science. Her works include Longitude (1995), Galileos Daughter (1999) and The Planets (2005).

Learn about key figures in science, spirituality, art and literature through revealing dialogues based on established fact. Written by a fantastic collection of authors and foreword writers gathered together to delve into the lives and achievements of some of the worlds greatest historical figures, this series is perfect for anyone looking for a quick and accessible introduction to the subject.

OTHER TITLES IN THE SERIES

Published

Conversations with JFK by Michael O'Brien;

Foreword by Gore Vidal

Conversations with Oscar Wilde by Merlin Holland;

Foreword by Simon Callow

Conversations with Casanova by Derek Parker;

Foreword by Dita Von Teese

Forthcoming

Conversations with Buddha by Joan Duncan Oliver;

Foreword by Annie Lennox

Conversations with Dickens by Paul Schlicke;

Foreword by Peter Ackroyd

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY DAVA SOBEL

When I think of Galileo, I am drawn to his eyes not just as metaphors for the wondrous sights they beheld, or as windows to his Catholic soul, but in their physical reality. His large, hungry eyes, dark as night, pained him from an early age, for they were vulnerable to infections and other infirmities, and they betrayed the great visionary towards the end of his life by denying him their sight. Blinded first in his right eye, and then in the left some months later, Galileo railed at the irony of his plight: This universe, which I with my astonishing observations and clear demonstrations had enlarged a hundred, nay, a thousandfold beyond the limits commonly seen by wise men of all centuries past, is now for me so diminished and reduced, it has shrunk to the meager confines of my body.

I used to believe the myth that Galileo had gone blind by staring at the Sun through his telescope, but he was much too wise for that. Averting his eyes, he had let the dangerous light fall through the long tube onto a sheet of paper, where he could safely trace the outlines of sunspots. These renderings are lovely things, though personally I prefer the brown washes he made of the Moon. Looking at his moonscapes today, its impossible to say which crater that is, straddling the border line between lunar day and lunar night. Some say Albategnius, others Ptolemy. But to argue that identity is to miss the point. All Galileo meant to capture here is the way the Suns rays filled valleys and climbed mountains on the Moon. With his artists eye, trained in perspective, he transformed the perfectly smooth crystalline orb of the Moon into an Earthlike, rocky world. Then he gauged the heights of the lunar mountains by the lengths of the shadows they cast.

People will tell you that Thomas Harriot in England looked at the Moon through a telescope before Galileo did. Thats true. But Thomas Harriot saw squiggles on a flat surface, and his drawings are unremarkable. Galileos images turned the cosmos inside out. No one extended the vision of humankind as much as he did. No one ever put more stock in perception than Galileo.

It took both bravery and bravado to trust his own eyes, even as he knew they bedevilled him. Recovering from one of his many illnesses, he recounted how I began to see a luminous halo more than two feet in diameter around the flame of a candle, capable of concealing from me all objects which lay behind it. As my malady diminished, so did the size and density of this halo, though more of it has remained with me than is seen by perfect eyes.

And yet, Galileos flawed eyesight exposed the flaws the rough edges and dark spots on heavenly bodies that initiated the field of observational astronomy.

If I could have questioned him over coffee, or perhaps a glass of wine, and looked into his imperfect eyes, what would he have seen in mine?

INTRODUCTION

During his lifetime Galileo was interviewed, or rather interrogated, only once, and he would gladly have done without it. This occurred in 1633 when he was on trial for teaching that the Earth moves. The questions that were put to him by the secretary of the Roman Inquisition were not exactly friendly, and his answers were hardly candid. He was a scientific superstar, in his estimation and in that of most of his contemporaries, and he would have loved to say, bluntly, what was on his mind.

In the imaginary conversation that follows, Galileo is interviewed by a sympathetic, but not overindulgent, visitor, and he is given the opportunity to express himself in the direct and occasionally abrasive manner that delighted his well-wishers and annoyed those who found him pushy and grasping. We shall hear him comment on the role of censorship, the importance of his scientific discoveries, his tiff with the Church, and his business sense. But he will also talk about the good times the fabulous girls and the memorable wine he had in Venice. At a deeper level, he will share with us his profound conviction that God had chosen him to make known a new heaven filled with an untold number of stars. We shall also listen to him describe how he faced up to his family responsibilities, how he coped with the devastating plague of 163033, and why he was considered a pundit by writers and painters. He will explain why he thought posterity would remember him.

Our society depends upon science, but we often know little about the personalities of those who practise it. Galileo was not a mild man, and not one to suffer fools gladly. He tended to regard astronomy and mechanics as his personal territory and trespassers risked being prosecuted. He was sensitive about his reputation and scornful when other scientists claimed to have made, independently, the same discoveries that he had. He became positively incensed if they dared suggest that they had preceded him. His temperament also put him on a collision course with theologians: he felt that they were wrong to commit themselves to an obsolete view of the physical world gleaned from the Bible; they did not understand why he was in such a hurry to toss the Earth into the air like a trial balloon as one of them objected.

Next page