Dogopolis

Animal Lives

Jane C. Desmond, Series Editor; Barbara J. King, Associate Editor for Science; Kim Marra, Associate Editor

Books in the Series

Displaying Death and Animating Life: Human-Animal Relations in Art, Science, and Everyday Life

by Jane C. Desmond

Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals: A Primate Scientists Ethical Journey

by John P. Gluck

The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War Twos Unknown Tragedy

by Hilda Kean

Animal Intimacies: Interspecies Relatedness in Indias Central Himalayas

by Radhika Govindrajan

Minor Creatures: Persons, Animals, and the Victorian Novel

by Ivan Kreilkamp

Equestrian Cultures: Horses, Human Society, and the Discourse of Modernity

by Kristen Guest and Monica Mattfeld

Precarious Partners: Horses and Their Humans in Nineteenth-Century France

by Kari Weil

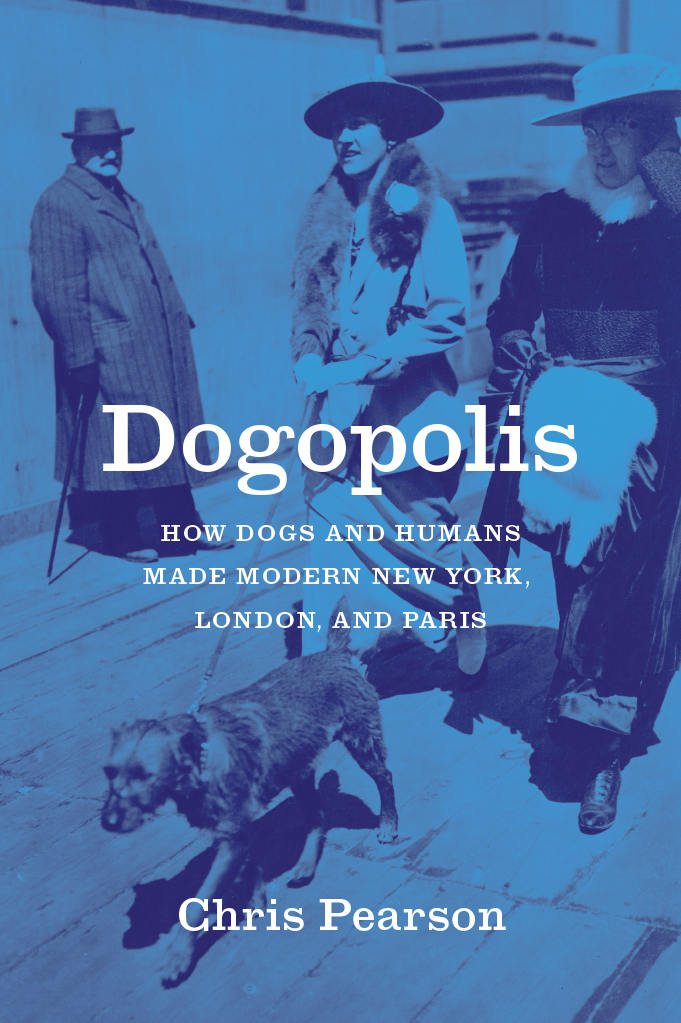

Dogopolis

How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris

Chris Pearson

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-79699-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-79816-5 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-79704-5 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226797045.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pearson, Chris (Environmental historian), author.

Title: Dogopolis : how dogs and humans made modern New York, London, and Paris / Chris Pearson.

Other titles: Animal lives (University of Chicago Press)

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago, 2021. | Series: Animal lives | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020056576 | ISBN 9780226796994 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226798165 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226797045 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: DogsBehavior. | Human-animal relationships. | City and town life.

Classification: LCC SF422.5 .P437 2021 | DDC 636.7dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020056576

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

The belief that humans and dogs share an ancient and unshakable bond is popular and pervasive. Dogs have lived and worked with humans since they were first domesticated thousands of years ago. This timeless and universal relationship, so the story goes, is marked by love and loyalty. Dogs are mans best friend. An importantif now often overlookedstep in the creation of this narrative was taken in rural Missouri. In 1870 lawyer George Vest praised the faithfulness of dogs during a lawsuit brought by a farmer who suspected a neighbor of shooting Old Drum, his favorite hunting dog. In arguing the farmers case, Vest declared that the one absolutely unselfish friend that a man can have in this selfish world, the one that never deserts him, the one that never proves ungrateful or treacherous, is the dog. Vests eulogy of Old Drum helped win the case, and the speech was reprinted as an ode to human-canine friendship and fidelity.

For nineteenth-century dog lovers, canine affection for humans was redemptive. As London-based writer, feminist, and antivivisectionist Frances Power Cobbe asked, How many lonely, deceived and embittered hearts have been saved from breaking or turning to stone by the humble sympathy of a dog[?]. Dogs kept humans emotionally healthy in the glow of their unconditional love. Such rhetoric was not restricted to Anglophone cultures. In a subtle subversion of seventeenth-century philosopher Ren Descartess famous depiction of animals as machines, dogs were love machines, according to French animal protectionist Baron de Vaux, and felt an extreme devotion to humans.

Scientists now conduct various experiments, including taking MRI scans of canine brains, to prove what many dog owners know instinctively: dogs and humans love each other. Animal history scholars complicate this rosy picture, however. They show that not only does the relationship between dogs and humans vary from place to place and across time, it is a relationship shaped by class, race, and gender. Seen in this light, Vests praise of Old Drum glorified white rural masculinity, rooted in farming and hunting in the wake of the Civil War, during which Vest had served as a Confederacy congressman.

I embrace the historical approach to human-dog relations. I argue that what many Europeans and North Americans now consider to be the universal and natural relationship between dogs and humans is deeply rooted in the distinct emotional histories of urbanization in the West. The three cities discussed hereLondon, New York, and Pariswere key sites of this transformation of human-canine relations. Innovations could be found in other European and North American cities, such as early experiments with police dogs in Ghent, Belgium. But as globally significant metropolises, developments in London, New York, and Paris were central to the transformation, influencing human-canine relations in other cities as well as in rural areas.

A model of Western human-canine relations eventually emerged, which I call dogopolis. This was the somewhat shaky agreement that slowly, and sometimes agonizingly, arose between the middle classes of London, New York, and Paris on how urban dogs should cohabit with urban humans in a civilized, healthy, and safe way. Dogs and humans were thrown together in these rapidly expanding and developing municipalities, generating a host of feelings: love, compassion, disgust, fear. Eventually, dogs were integrated into city life in line with middle-class emotional values that centered on revulsion to dirt, fears of vagabondage, anxieties about crime, and the promotion of humanitarian sentiments. By the late 1930s, fears of biting and straying dogs had diminished; canine death had been rendered mostly acceptable through the management of canine suffering; dogs had fulfilled emotionally satisfying roles as pets and as police dogs (who in theory soothed worries about criminality); and the first steps had been taken to reduce the disgust provoked by canine defecation. Dogs straying and defecating were tamed, their suffering reduced, and their thinking harnessed. Underscoring this transformation was dogs actual and perceived ability to bond emotionally with humans.

Dogopolis was not an inevitable end state. It emerged through choice, contingency, and conflict. Its complicated creation was also part of a wider reworking of urban human-animal relations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that often focused on the management of animals in urban public spaces. By the mid-1870s, for instance, New Yorks Sanitary Code included regulations addressing horse diseases, animal slaughter, and tanning and rendering processes as well as restrictions on stray dogs.

Dogopolis did not obliterate earlier aspects of human-dog relations. Some dogs kept on straying and biting, police canine units did not work out straightaway, and dog mess remained an unresolved problem. Nor is it a fixed state, having evolved since the 1930s. Notable developments include the introduction of widespread neutering, the firm establishment of police canine units after World War II, and the pooper-scooper revolution of the late 1970s. Dog hating has also continued: see calls in the 1970s and 1980s to ban dogs from Paris because of dog mess. But the place of dogs within the Western city was assured and a model of urban human-dog cohabitation established, within which Western urbanites still reside.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).