THE BRIDGE AT DONG HA

The latest edition of this work has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Edward S. and Joyce I. Miller.

1989 by the United States Naval Institute

Annapolis, Maryland

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

First Bluejacket Books printing, 1996

ISBN 978-1-61251-157-3 (eBook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Miller, John Grider, 1935

The bridge at Dong Ha / John Grider Miller.

p. cm.

1. Dng H (Vietnam), Battle of, 1972. I. Title.

DS557.8.D66M55 1989

959.70493dc19

89-2908

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

14 13 12 11

CONTENTS

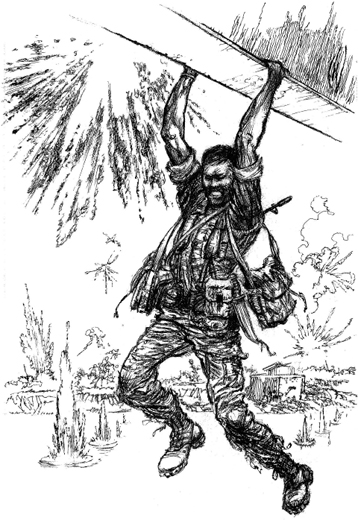

B ridges have figured prominently in the annals of war. Time and again, the course of history has turned on the destruction or saving of these vulnerable structures so necessary to the transit of armies and supplies. Because of the nature of the work, destruction can frequently be credited to the ingenuity and drive of individual men, whose names abound in both legend and history. What follows is the real story of a Marine Corps hero, John Walter Ripley, who on Easter Sunday, 1972, almost singlehandedly took on a massive concrete and steel bridge to derail the carefully prepared spearhead attack of the North Vietnamese Army at the Cua Viet River near Dong Ha. For this, he can be compared to the legendary Horatius memorialized by nineteenth-century English historian and poet Thomas Macaulay. In the sixth century B.C. Horatius, virtually unassisted, held back the army of Emperor Tarquin while his Roman soldiers destroyed a bridge over the Tiber River.

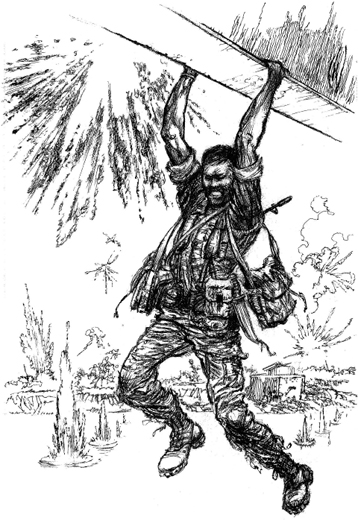

Ripley blew up the bridge at Dong Ha by improvisation, swinging hand over hand underneath, dangling from the supporting girders, wrestling boxes of TNT through the channels, bleeding, passing out, ignoring radio chitchat from a distant chain of command about saving the structure for a counterattack. He worked on, despite the sounds and reports of widespread panic as the NVA juggernaut bore down on central South Vietnam, threatening the reorganization of a defense in depth.

John Ripley was an experienced warrior, alone with the courage of his convictions. All the physical and mental and spiritual strength he had built up in a lifetime of service found application on that Easter Day. Horatius would have been lucky to be in his company. The words Thomas Macaulay put into the great Romans mouth matched the commitment and sensitivity of the John Ripley I know:

To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late;

And how can a man die better

Than facing fearful odds

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?

Ripleys ordeal under the bridge occurred at a time when nearly all Americans had left Vietnam. And like everything else about the war as it dragged on, the results were only halfway gratifying at best. Before another month had elapsed, the North Vietnamese Army had fought its way across upstream bridges to the west, confronted such reinforcements as could be rounded up by the South Vietnamese, and settled for another standoff at the My Chanh River, fifteen miles south of the Cua Viet.

But what a save Ripley made, considering the inevitable had that bridge at Dong Ha been left standing to serve the tank column thundering southward on Easter Sunday! He changed the course of the war. With newly stabilized battle lines, the American bombing resumed in North Vietnam, and it was that effort which ultimately blasted us prisoners of war out of Hanoi. Who knows how things would have come out otherwise? It took the North Vietnamese three years to regroup and prepare for another large-scale invasion.

When Ripley looked at the bridge on Easter morning, he knew exactly how it was constructed because five years earlier he had examined and crossed it time and again. In 1967 he had been fighting near it, along the DMZ, with a regular U.S. Marine Corps unit and thousands of other Americans. In 1972 he was back at the DMZ, this time fighting for his life in a desperate rear-guard action alongside the South Vietnamese. He did so voluntarily. Its easy to give your all when victory appears to be around the corner. The real hero is the man whose sacrifices for his brothers-in-arms come from a sense of sheer duty, even though he knows his efforts are probably doomed to failure.

Surprising to some, perhaps, but it is a fact that men with such a sense of duty are not rare in the U.S. Marine Corps. John came from a Virginia home in which awareness of family heritage and honor was a staple of the nurturing process. That he had ancestors who fought in every American warincluding five in the Revolutionary War and some on both sides in the Civil Warwas a lesson not lost on him. He served the ashes of his fathers and the temples of his gods. And I write this as one aware of the extra degree of commitment it took for men like himmen who had devoted hard, painful years to the fighting in Vietnam and who could see that Americas national resolve was on the waneto stay the course.

VICE ADMIRAL JAMES B. STOCKDALE,

U.S. NAVY (RETIRED)

THE BRIDGE AT DONG HA

H ad it not been for the bridge, the South Vietnamese town of Dong Ha would be remembered today by no one but its own people and the U.S. Marines who fought there in the late 1960s. For years the town, the northernmost one on National Highway 1 in South Vietnam, was little more than a wayside stop serving travelers bound for points north and west. But by the spring of 1972, Dong Ha had become the end of the line. North Vietnamese units were moving freely through the northwestern sector of Quang Tri Province. North of Dong Ha, nothing could be visited without peril. The DMZthe misnamed demilitarized zonelay roughly twelve miles in that direction. About the same distance to the west, along National Highway 9, a former U.S. Marine Corps base called Camp Carroll guarded South Vietnams northwest flank. Camp Carroll was garrisoned by the Fifty-Sixth Regiment of the ARVN, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.

Dong Ha squatted along the south bank of the Cua Viet River, which flowed eastward from the narrow headwaters of the Cam Lo River. Swollen by the winter monsoon, the Cua Viet measured five hundred feet wide when it surged past Dong Ha toward the South China Sea ten miles away. Small boats in the river had to contend with a swift current and fast-moving debris.

In 1967, SeaBees from a U.S. Navy construction battalion built a two-lane highway bridge across the Cua Viet to meet the growing demands of military traffic up and down Highway 1, the countrys only north-south artery. An old French-built bridge just upstream had become inadequate for military purposes, as had a heavily damaged railroad bridge farther upstream, whose spans lay rusting in the river.

Next page