Copyright 2014 by Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2014

14 15 16 17 18 19 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-3361-7 (cloth) 978-0-8156-5273-1 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mattawa, Khaled.

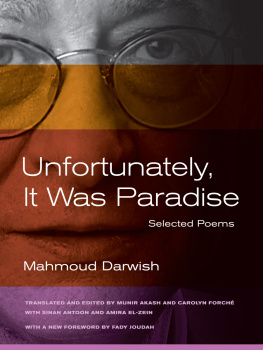

Mahmoud Darwish : the poets art and his nation / Khaled Mattawa. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8156-3361-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8156-5273-1 (ebook)

1. Darwish, MahmudCriticism and interpretation. 2. Politics and literature.

I. Title.

PJ7820.A7Z7389 2014

892.7'16dc23 2014006798

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Halima, my mother.

For her bread and her coffee.

Khaled Mattawa was born in Benghazi, Libya, in 1964 and immigrated to the United States in 1979. He received an MFA in creative writing from Indiana University and a PhD from Duke University. Mattawa is the author of four books of poetry, Tocqueville (New Issues Press, 2010), Amorisco (Ausable Press, 2008), Zodiac of Echoes (Ausable Press, 2003) and Ismailia Eclipse (Sheep Meadow Press, 1996). He has translated nine books of contemporary Arabic poetry by Adonis, Saadi Youssef, Fadhil Al-Azzawi, Hatif Janabi, Maram Al-Massri, Joumana Haddad, Amjad Nasser, and Iman Mersal, and has coedited two anthologies of Arab-American literature. Mattawas latest volume of poetry, Tocqueville, won the 2011 San Francisco Poetry Center Book Award and the Arab American National Book Award. His translation of Adoniss Selected Poems won the PEN USA Center annual poetry in translation prize. Mattawas awards include the 2010 Academy of American Poets Fellowship Prize, a Ford/United States artist for 2011, the Alfred Hodder fellowship from Princeton University, a Guggenheim fellowship, an NEA translation grant, and three Pushcarts. He is an associate professor of Creative Writing at the University of Michigan.

Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

Contents

Preface

One of the great privileges of my life was having the first Palestinian I met in Palestine be the poet Mahmoud Darwish. It was June 2000, and I had arrived as a Fulbright scholar to Palestine. The American embassy driver taking me to Ramallah spoke in broken English so quietly that I could never tell what he was saying or whether his native language was Hebrew, Arabic, or Russian. Along with us for part of the ride was an American military officer who said not a word and radiated an intense hostility that seemed to make the van go faster than it would have otherwise. I was relieved to arrive at last in Ramallah and to open the noisy iron gate of the Sakakini Center. I quickly climbed a short flight of stairs and tried to open the centers front door. When it did not open, someone shouted from inside, You need the downstairs door. I said thanks, and the voice replied with a casual Marhaba! (Welcome!) Just as I began to head back, I paused because something about the voice held me. Turning around, I quickly peered through the window to see who spoke. Indeed, it was Mahmoud Darwish sitting at a large, ornate, and rather neat desk; he was the first to welcome me into Palestine.

More importantly, of course, I want to credit Darwish for initiating me into poetry as I know and practice it. In December 1988, in an Arab grocery store on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, I found dusty copies of Mahmoud Darwishs early books among the sacks of dried goods, cassettes, coffee kettles, and prayer rugs. I had been writing for a couple of years by that point, but it had been only a few months since I allowed myself into poetry. That night, in my room, I read a little bit of Darwish, translated it into English, and went back to reading other books of poetry I had brought with me. In between reading and translating, I put down ideas for poems, and even a few lines of my own.

Translating Darwish as I read English verse, I received two floods of poetry: the poetry I longed to write and the language I wanted to write poetry in. I suspect that my writing mode remains positioned at this nexus of two desires, a braiding of lack and abundance. What struck me most about Darwishs poetry then was not its politics or its Palestinianness, but the fact that it satisfied my inner poetic ear and eyethe cadence of Arabic verse Id inherited in my upbringing and the deep imagery I associated with modern verse. Darwishs was poetry Id known before, but it was also poetry I was discovering anew.

My personal connections to Darwish are typical of his influence and legacy. Born in 1941, seven years before the Nakba (catastrophe), Mahmoud Darwish has guided millions to Palestine, including the Palestinians themselves. His poem Identity Card, first recited in 1957 in a Nazareth movie house, was in essence the calling card that the Palestinians flung at their Israeli occupiers. Its impact on Palestinians and Arabs in general could not be exaggerated. Darwishs poems to Rita and his well-known A Soldier Dreams of White Lilies introduced the Israelis to the Palestinians and vice versa. Darwish instinctively knew that in order to assert the humanity of his people, he needed to likewise assert the humanity of his adversaries. Because he was committed to his art, Darwish knew that the road to his nation had to be demanding in order to be fulfilling and fulfilled.

Darwishs poems of exile after he left for Cairo in 1971, his postBeirut poems of the mid-1980s, and his poems of the Oslo Accord period comprise a complex and varied meditation that is particular to the Palestinian saga of displacement and struggle. If he had written only those poems, he would easily be credited for composing a body of work that belongs among the twentieth centurys best poetry.

There is hardly a moment in Palestinian history that Darwishs poetry has not treated. Coauthoring the Palestinian declaration of independence, chronicling the 1982 siege of Beirut, or remarking on cultural and political developments in Israel, Darwish and his lyrical voice can be found in masterful works of prose in addition to his poetry. No conversation among Palestinians or any presentation of themselves to the world occurs without alluding to his work. This is not to praise Darwishs genius, but rather to say that the Palestinian ethos was embodied in him because he worked tirelessly and continuously to attain this level of relevance and depth.

For decades, the Palestinian people were disparaged as their Zionist occupiers flooded the world with a contradictory myth of fragility, military genius, and cultural superiority. Now we can see that the Palestinians, whose dream of a nation-state is still under threat, have largely reversed the worlds cultural perception of them. Who can now say, in the worlds court of public opinion, that the Palestinians should be denied their dream? The myth of Israel as the sole democracy in the Middle East that had greened the desert is being continuously supplanted by the reality of Israel as a militarized state whose colonial-settler citizens are confiscating Palestinian lands daily. On the Palestinian side, even in Hamas-led Gaza, the Palestinians emerge mostly as civilians building a society where arts and culture have provided a more solid backbone than militancy. Precisely because of his impact on Palestinian artists and cultural activists around the world, Darwishs contribution to this element of the Palestinian identity is undeniable. As such, Darwish continues to provide a metonymic representation of Palestine. His poems express Palestinians suffering as an occupied people, their longing for peace, the particularities of their relationship to the land and to one another, their feelings for their enemies, the anguish of their protracted exile, and their endurance through a history filled with disappointments.

Next page