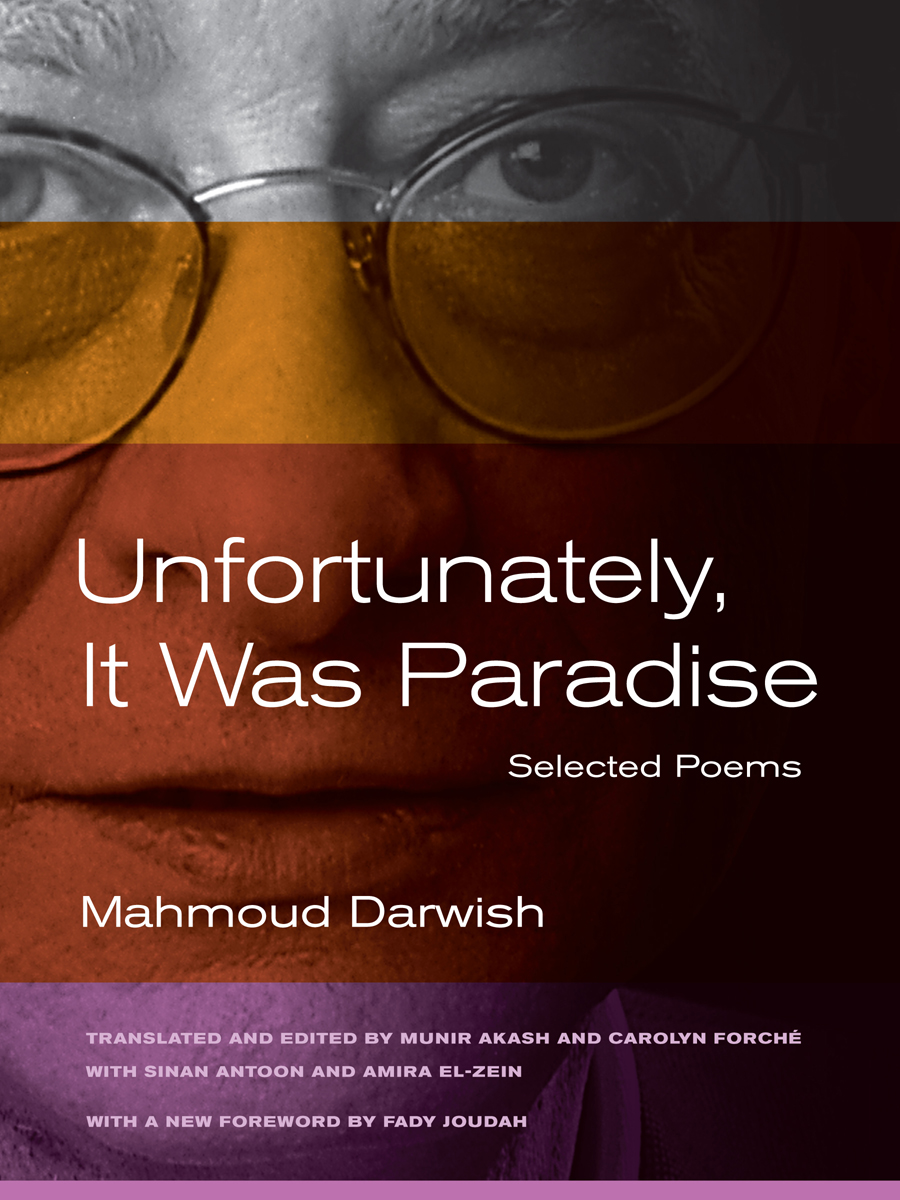

Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Mahmoud Darwish Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Selected Poems Translated and Edited by Munir Akash and Carolyn Forch (with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein) With a New Foreword by Fady Joudah

Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Mahmoud Darwish Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Selected Poems Translated and Edited by Munir Akash and Carolyn Forch (with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein) With a New Foreword by Fady Joudah  University of California PressBerkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England 2003, 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN : 978-0-520-27303-0 eISBN : 9780520954601 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Darwish, Mahmoud. English. English.

University of California PressBerkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England 2003, 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN : 978-0-520-27303-0 eISBN : 9780520954601 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Darwish, Mahmoud. English. English.

Selections] Unfortunately, it was paradise : selected poems / Mahmoud Darwish ; translated and edited by Munir Akash and Carolyn Forch, with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-520-23754-4 (paper : alk. paper) I. II. II.

Forch, Carolyn. III. Title. PJ7820 . A 7 A 222003 892.716dc212002068454 Printed in the United States of America 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Holland Enviro100, a 100% post-consumer fiber paper that is FSC certified, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with renewable biogas energy. It is acid-free and EcoLogo certified.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Lannan Foundation. Pero yo ya no soy yo Ni mi casa es ya mi casa. But now I am no longer I, nor is my house any longer my house. Federico Garca Lorca Contents Acknowledgments Any collection of this sort requires the support and assistance of more people than can be named here. Each of them knows who he or she is, and to each of them many thanks. I offer my sincere appreciation to the Lannan Foundation for their generosity and their unfailing support.

Patrick Lannan and the wonderful family of his foundation by their insight, bravery, and service to humanity have taught me dedication. Special thanks to the poet Mahmoud Darwish for his patience in answering my many questions and, of course, for his guidance and very helpful comments along the way. Each poem in this collection has been carefully selected from Darwishs entire work in collaboration with the poet himself. This enterprise could not have been possible without an exceptional team of translators. All have known Darwish and his work for a long time. When I expressed to Mahmoud Darwish my desire to translate this collection, he asked me to work in collaboration with a leading American poet who could give the translations a single consistent tone.

What Carolyn Forch has done here, in this very short period of time, is an enterprise short of miraculous. She recreated the poems translated with a different sensibility and made them harmonious in a single voice. For this and for her wholehearted dedication I cant thank her enough. A heartfelt expression of gratitude to Daniel Moore and Laura Cerruti for their painstaking review and exceptional editorial expertise. Their drive, vision, and unique poetic sensibility turned a dream into reality. Very special thanks to Harry Mattison, Ibrahim Muhawi, and Kinda Akash for their insightful reading and their many helpful suggestions, and to Caroline Roberts and Kaia Sand for their meticulous copy editing.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors and publishers of the following journals in which some of these poems were first published: Tikkun, Salmagundi, Brick, American Poetry Review, and Fence. Finally, I have to admit that all the great work in this collection exists thanks to these wonderful people and that every mistake in it is mine. Munir Akash Introduction Mahmoud Darwish is a literary rarity. Critically acclaimed as one of the most important poets in the Arabic language and beloved as the voice of his people, he is an artist demanding of his work continual transformation and a living legend whose lyrics are sung by fieldworkers and schoolchildren. Few poets have borne such disparately bestowed adulation, nor survived such dramatic vicissitudes of history and fate as Mahmoud Darwish; even fewer have done so while endeavoring to open new possibilities for poetry while assimilating one of the worlds oldest literary traditions. His poetry has been enthusiastically embraced since the publication of his first volume, Leaves of Olive, in 1964.

After the Arab defeat in the 1967 war, Darwish raised his voice in searing lyrics confronting the pain of everyday life for Palestinians. In a realism stripped of poetic flourish, the poetry of resistance was born. With Nerudian transparency, his poems of the sixties and early seventies reflected his pain over the occupation of his homeland and his lingering hopes for its liberation. In the intervening years, the poetry of Darwish exemplified a brilliant artistic restlessness, with each volume opening new formal territory and poetic concerns. With the publication of this collection, Darwish will celebrate his sixty-first birthday and nearly four decades of writing. He is the poet laureate of Palestinea poet sharing the fate of his people, living in a town under siege, while providing them with a language for their anguish and dreams.

Any serious study of his work must take into account the context in which it was written: the years of exilic wandering and survival; the aesthetic, metaphysical, and political struggles particular to this poet. Mahmoud Darwish was born in the village of Birwe, in the district of Akka (Acre) in upper Galilee, Palestine, on March 13, 1942. When he was six years old, the Israeli Army occupied and subsequently destroyed Birwe, along with 416 other Palestinian villages. To avoid the ensuing massacres, the Darwish family fled to Lebanon. A year later, they returned to their country illegally, and settled in the nearby village of Dayr al-Asad, but too late to be counted among the Palestinians who survived and remained within the borders of the new state. The young Darwish was now an internal refugee, legally classified as a present-absent alien, a species of Orwellian doublethink that the poet would later interrogate in his lyric meditation The Owls Night, wherein the present is placeless, transient, absurd, and absence mysterious, human, and unwanted, going about its own preoccupations and piling up its chosen objects.

Like a small jar of water, he writes, absence breaks in me. The newly alienated Palestinians fell under military rule and were sent into a complex legal maze of emergency rulings. They could not travel within their homeland without permission, nor, apparently, could the eight-year-old Darwish recite a poem of lamentation at the school celebration of the second anniversary of Israel without subsequently incurring the wrath of the Israeli military governor. Thereafter he was obliged to hide whenever an Israeli officer appeared. During his school years, and until he left the country in 1970, Darwish would be imprisoned several times and frequently harassed, always for the crimes of reciting his poetry and traveling without a permit from village to village. Birwe was erased from land and map, but remained intact in memory, the mirage of a lost paradise.

In 1997, the Israeli-French filmmaker, Simone Bitton, went to what had been Birwe to film Darwishs childhood landscape, but found nothing but ruins and a desolate, weed-choked cemetery. On April 16, 2001, Israeli bulldozers began paving a new road through the graves, unearthing human remains throughout the site. The vanished Palestinian village became, for the displaced poet, a bundle of belongings carried on the back of the refugee. Denied the recognition of citizenship in the new state, Darwish settled on language as his identity, and took upon himself the task of restoration of meaning and thus, homeland: Who am I? This is a question that others ask, but has no answer. I am my language, I am an ode, two odes, ten. This is my language.

Next page

Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Mahmoud Darwish Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Selected Poems Translated and Edited by Munir Akash and Carolyn Forch (with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein) With a New Foreword by Fady Joudah

Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Mahmoud Darwish Unfortunately, It Was Paradise Selected Poems Translated and Edited by Munir Akash and Carolyn Forch (with Sinan Antoon and Amira El-Zein) With a New Foreword by Fady Joudah  University of California PressBerkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England 2003, 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN : 978-0-520-27303-0 eISBN : 9780520954601 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Darwish, Mahmoud. English. English.

University of California PressBerkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England 2003, 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN : 978-0-520-27303-0 eISBN : 9780520954601 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Darwish, Mahmoud. English. English.