HOT, HOT CHICKEN

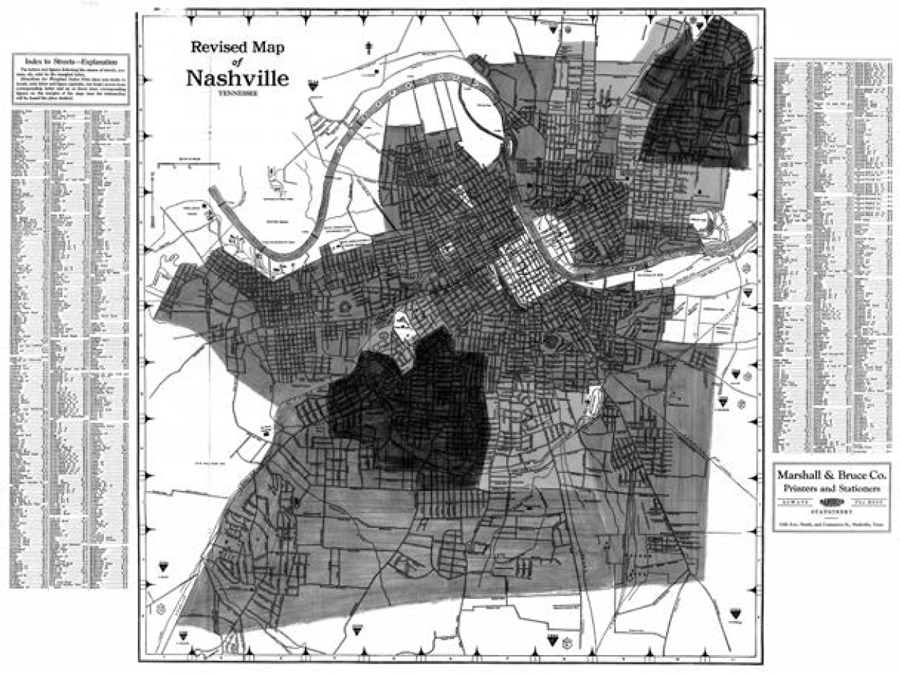

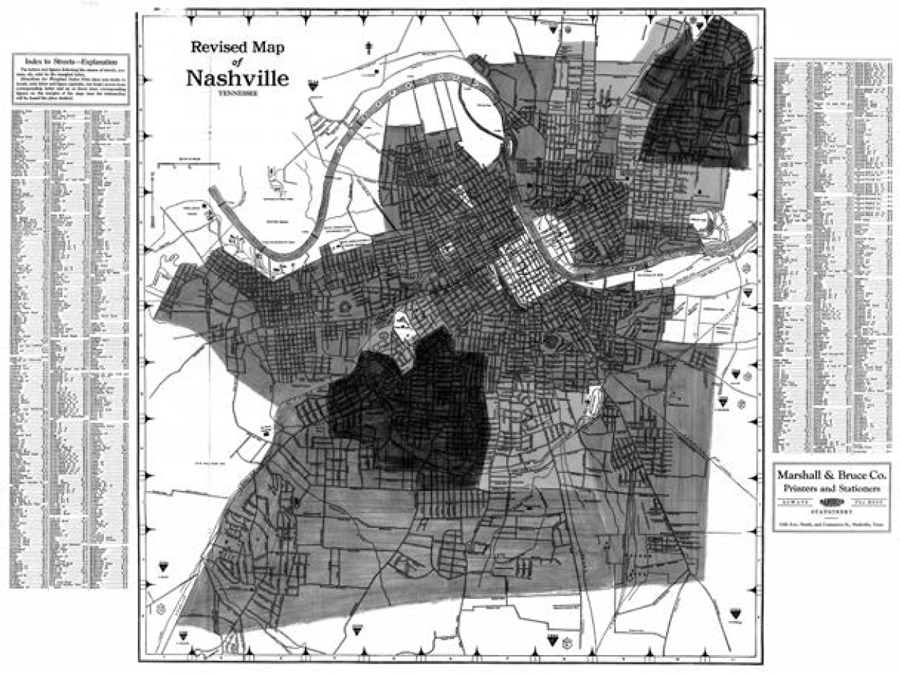

Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., Mapping Inequality, American Panorama, edited by Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers.

HOT, HOT CHICKEN

A NASHVILLE STORY

RACHEL LOUISE MARTIN

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY PRESS

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

Copyright 2021 Vanderbilt University Press

All rights reserved

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Martin, Rachel Louise, 1980 author.

Title: Hot, hot chicken : a Nashville story / Rachel Louise Martin.

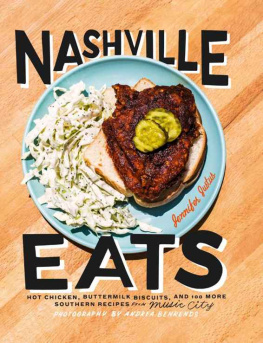

Description: Nashville : Vanderbilt University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The history of Nashvilles Black communities through the story of its hot chicken scene, from the Civil War through the tornado in March 2020Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020046179 | ISBN 9780826501769 (paperback) | ISBN 9780826501776 (epub) | ISBN 9780826501783 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Princes Hot Chicken (Restaurant)History. | Fried chickenTennesseeNashvilleHistory. | African AmericansTennesseeNashvilleSocial life and customs. | African AmericansTennesseeNashvilleHistory. | Prince family.

Classification: LCC TX945.5.P687 M37 2021 | DDC 647.95768/55dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020046179

To my parents.

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book could not exist without the hot chicken makers whose lives and experiences Ive attempted to reconstruct. I am especially grateful to two in particular. Back in 2015, Andr Prince Jeffries, current owner of Princes Hot Chicken, sat down with me for several hours in the midst of a busy service to explain how race and hot chicken had intertwined in Nashvilles history. Her insights into the citys past and present helped me clarify the ways this story was unique to Nashville and the ways it was true of cities across the nation. And then when it came time for me to write the book, Dollye Matthews, co-owner of Boltons Hot Chicken and Fish, shared how her familys experiences both mirrored and diverged from the Prince familys stories. I am grateful to both of you for sharing your memories and your perspectives with me.

Thank you also to the other Nashvillians whose voices contributed to this book: Keel Hunt, Bill Purcell, Learotha Williams Jr., and Steve Younes. I appreciated your willingness to share your thoughts and memories. And thank you to Franklin historian Thelma Battle, who helped me fill out the Prince familys pre-Nashville story. Her decades of research into the Black experience in Williamson County has created an invaluable archive for anyone wanting to know about the lives of those omitted from other records.

I cannot overlook Chuck Reece at The Bitter Southerner. When I pitched How Hot Chicken Really Happened to him back in 2015, I was a historian who wanted to write, but I only had a couple of clips in my portfolio. He gambled on me. Then he led me through the process of turning my research into an essay other people would want to read. His edits were some of the best writing classes Ive had.

I am grateful to the team at Vanderbilt University Press for the opportunity to transform my essay into a book. Zack Gresham, my editor, stayed committed to this project even when my early drafts should have scared him off. Thank you for giving me the space to see where my research might lead me and the deadlines that kept me focused on the key questions of the narrative. And thanks also to Betsy Phillips, a fellow writer and a marketing guru, who knew just when I needed a cheerleader.

Thanks to Sam Warlick, who pulled some marathon reading sessions, double-checking my understanding of Nashvilles development and helping me cull some of the research that had blinded me to the bigger storyline. And to the rest of my friends who listened to me worry about missing city directory entries and suggested where I might find lost divorce records and let me interrupt our conversations to spurt random facts about Nashville, thank you. I only have one more favor to ask. Next time I say Im going to research and write a book in less than six months, tell me no.

And in everything I write, I owe a debt to Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, my graduate school advisor, who taught me how to search for and listen to the voices purged from the official records.

Finally, I am grateful my parents who listened and explored and distracted and believed and asked and brainstormed and read and fed and laughed and loved me through this project and all the others Ive undertaken. Thank you seems inadequate.

INTRODUCTION

Set It Up

A Tennesseans Take on Mise en Place

A smallish man putters behind the warped glass storefront. Surprised to see signs of life inside the damaged strip mall restaurant, I park my Prius and watch him work his way around a jumble of white ladder-back chairs cantilevered against the middle window. The man grabs a five-gallon bucket, one of those pails that could hold anything from paint to Quickrete to roof sealer, and lugs it past a stack of fire-proof insulation. I lose sight of him when he heads toward the back of the building where the kitchen used to be.

Driving by, I hadnt noticed how much had changed in the fourteen months since the accident that shut down this location, but now that Ive stopped, I catalogue the differences. Inside, an unfamiliar trio of booths faces the far wall. These arent the six historic white wooden booths that Andr Prince Jeffries had trucked along with her when she moved the family business here to East Nashville. Those benches had heft. They curled and curved like high-back church pews. And like all good church pews, they were unpadded, a guarantee that if the foods afterburn didnt sober up Jeffries late-night crowd, the seats would get them out the front door before they decided to sleep off their weekend pleasures. But the booths in the left-hand window today have no such stately heritage; they are the same patchwork of blue and red vinyl that appears in every nameless pizza joint.

From what I can see, just about everything in the restaurant has been altered. Princes was multi-coloredcream walls, slate ordering window, turquoise restroom hallway. And all of it was covered in family memorabilia and community notices and autographed headshots and Christmas lights. The new restaurant wears a uniform navy peacoat blue. Someone has switched out the sign; Princes Hot Chicken Shack is now labeled Caf 12-3, the name of a long-defunct Nashville restaurant.

Even the front windows are washed clean of paint, wiped clear of the cartoon drawing of a red-shirted Thornton Prince III wearing a crown and hoisting a monster-sized steaming leg of fried chicken over his head. Only the hours remain, stuck to the door in peeling vinyl decals:

TUESDAY THURSDAY

11:00 am 11:00 pm

FRIDAY

11:00 am 4:00 am

SATURDAY

2:00 pm 4:00 am

Gone too is the press of regulars, celebrities, and tourists who had visited this East Nashville strip mall. The last time I was here, customers pushed through the door and lined up along the turquoise wall, inching toward the woman ringing up orders. A few were like me, occasional visitors needing a quick hit of spice. Most were friends. They chatted with each other, with the staff, with Andr Jeffries, with the cooks hidden in the kitchen. Then everything paused when the woman in the window yelled a number. A customer would shove forward to grab their brown paper bag of food. That early on a Thursday, they would be taking their meal to go. The chickens grease and sauce would quickly saturate the paper, so theyd wrap their bundle in a white plastic bag plucked off a nearby counter.