Preface and

Acknowledgements

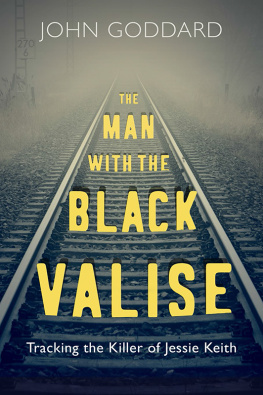

Photo by John Goddard

T housands of subway riders glimpse it absently every day. A portrait of William Lyon Mackenzie peers from the platform mural at Queen Station, his face as round and orange as a wheel of cheese, his expression as knotted as when he first encountered Upper Canadas stifling elite. Mackenzie served as Torontos first mayor and led the star-crossed Rebellion of Upper Canada. He was the grandfather of William Lyon Mackenzie King Canadas tenth prime minister, whose own orange-pink visage graces the Canadian fifty-dollar bill and died three blocks from his subway-wall portrait, at a house that the city preserves as a museum.

One day I decided to visit the house. Like many people, I knew of Torontos heritage museums, and had been meaning to get around to seeing them. Mackenzie House, as it is called, proved a revelation. I discovered something called a Rebellion Box, one of hundreds of small wooden boxes tenderly carved for mothers and sweethearts by accused rebels awaiting trial in Torontos cold, damp jail. Upstairs, I saw the bedroom where Isabel Grace Mackenzie, nicknamed Bell, slept during her adolescence and young adulthood, before becoming Mrs. Isabel King and mother to a future prime minister. In a back room, I briefly operated an 1845 Washington rolling flatbed press, of the kind Mackenzie used late in his career to foment against official self-interest and hypocrisy.

I also learned something else. The citys heritage museums are interconnected. The builder of what is now the Spadina House Museum once worked as a teenage apprentice in Mackenzies print shop. The home of David Gibson, one of Mackenzies fellow rebels, survives as the Gibson House Museum on Yonge Street, at North York Centre. The builder of Colborne Lodge in High Park led a military detail against Mackenzie, Gibson, and the rebel uprising.

Beyond the Mackenzie link, I saw that the citys heritage-house museums complement each other in many ways. The properties include a townhouse, a stately home, a country inn, an industrial site, a schoolhouse, and a military fort. Ken Purvis, coordinator at Montgomerys Inn, pointed out that the museums, if taken together, begin to form a coherent community, like a lost colonial village reunited.

They also form a single museum institution. In Toronto, people talk of the need for a city history museum, rarely recognizing that the Economic Development and Culture Division already runs a sprawling heritage-museum network. Under a single administration, the division incorporates eight museums in fifty-five buildings and outbuildings on ten sites. It holds 150,000 artifacts in those buildings and two warehouses, and occupies offices at Metro Hall, at the corner of King and John Streets. Full-time staff members sometimes switch places within the museum institution. Part-time personnel sometimes hold jobs at two or three venues at once.

Occasionally the network is threatened. In 2011, as a budgetary measure, Mayor Rob Ford proposed to close four of the venues: Montgomerys Inn, Gibson House, Zion Schoolhouse, and the Market Gallery. The unsung gems of our city, councillor Joe Mihevc called them during the protests that followed. Ford withdrew his measure, the museums were saved, and the publicity caused a spike in attendance.

For me, visiting the museums proved a rich experience. Exploring the past deepened my sense of connection to the city. I live downtown, near what was once the Town of York. After a while, I could easily imagine William Lyon Mackenzie walking through the neighbourhood, and such people as Anglican cleric John Strachan, or perhaps Attorney General John Beverly Robinson, crossing the street to avoid him.

I had one complaint. After every museum visit, I always wanted to know more, but there were no books to buy, no pamphlets to take away. Mackenzie has had his biographers, and Fort York its military historians, but otherwise materials relating to the museums proved difficult to find, and nothing at all presented the museums as a community.

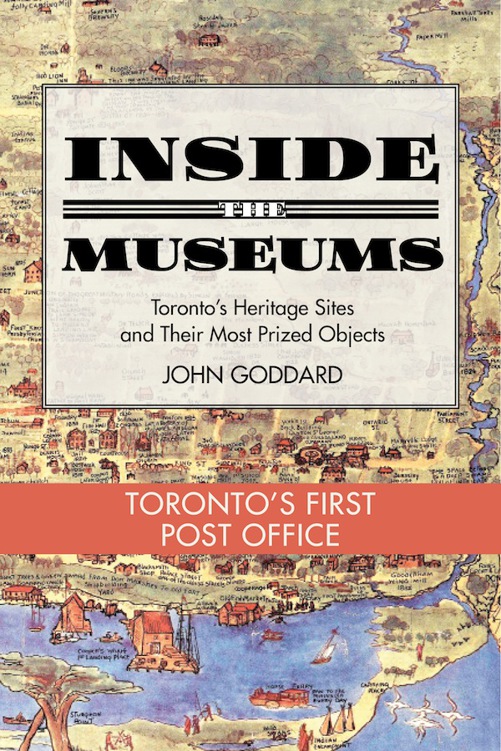

I resolved to write the book that I wanted to read. In doing so, I took the freedom to venture beyond the city-run network. Of the eight Economic Development and Culture Division museums, I included six in the book: Mackenzie House, Gibson House (with Zion Schoolhouse), Colborne Lodge, Montgomerys Inn, Spadina House, and Fort York. I also included the Market Gallery, a former city hall, administered by the City of Toronto Archives. I added three others: Campbell House, run by the Advocates Society with a partial subsidy from the city; The Grange, at the Art Gallery of Ontario; and Torontos First Post Office, an independent non-profit organization.

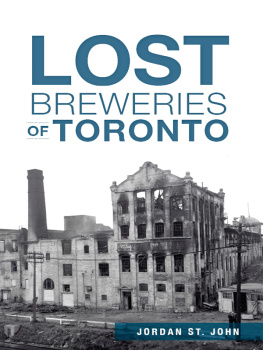

To keep the number at ten, I had to cut two Economic Development and Culture Division venues Todmorden Mills Heritage Site and the Scarborough Museum. Both are worth a visit. Todmorden Mills, nestled in the Don Valley, started as a sawmill in 1793 and developed into a papermaking business, gristmill, brewery, and gin distillery. It is undergoing a major reinterpretation to reflect industrial life in the first half of the twentieth century. The Scarborough Museum sits on land cleared in 1799 by Scarboroughs first settler, David Thomson. Descendents through his older brother, Archibald, include the late newspaper baron Roy Thomson, after whom Roy Thomson Hall is named. Roys grandson, David Thomson, is chair of the global media empire Thomson Reuters and currently Canadas richest person, said in 2013 to be worth more than twenty billion dollars.

Each of the books chapters divides into four sections:

- Personal Story, such as the appalling instructions that Robert Baldwin left in his will;

- Walk-Through, pointing out highlights of the historic site;

- Prized Object, such as George Lambs Rebellion Box, or the floor clock that Eliza Gibson rescued from imminent destruction by government militiamen, and;

- Neighbouring Attractions, such as Victoria Memorial Square near Fort York, where the valiant Captain Neal McNeale is buried.

All ten museums can be reached easily by public transit. Even far-flung Gibson House and Montgomerys Inn lie within short walking distance of a subway station.

Admission charges are reasonable, sometimes free. The Market Gallery and Torontos First Post Office are free (a two-dollar donation is suggested). Art shows at Campbell House are free. The Grange is free on Wednesday evenings. Some venues participate in Doors Open Toronto and the Scotiabank Nuit Blanche arts festival, with free admission on both occasions. A Heritage Toronto membership comes with free museum admission to all the museums except for the Art Gallery of Ontario. The Cultural Access Pass, given to new Canadians for their first year of citizenship, offers free admission to most of the museums, including the AGO. Anybody with a Toronto Public Library card can borrow a free family pass to any of the city-run museums and the AGO, on a first-come first-serve basis.