Thanks to Burke Hilsabeck for help with the research; to Cyntthia Cotts for the fact-checking; to Jeremy Medoff for taking the photographs; to Jean Brown for transcribing tapes of various interviews; to Andrew Wylie and Jeff Posternak at the Wylie Agency; to everyone at FSG, especially my editor, Jonathan Galassi; to my sister, Sharon, to my brother, Steven, and to my parents, Herb and Ellen; to Marvin Eisenstadt and Gladys Eisenstadt for telling me some of their stories; to my friends and family, those who think a lot of me and those who dont; to my wife, Jessica; and special thanks to Francis Albert Sinatra.

Several years earlier, while Ben was recovering from his allergic reaction to the antibiotics, my parents scheduled their return flight to East Hampton Airport. They asked if I wanted a seat on the flight. My brother and sister would be going. The girl I had been dating that summer was scheduled to fly to Chicago that same morning. I decided I would drop her at her flight, then meet my family. I had broken up with her the night before. She expressed no emotion when I did this, simply turned over and went to sleep. I carried her bags through the terminal. When we reached Security, she started to cry. The tears hung at the end of her lashes. But they did not touch me. Now is the time when your girlfriend cries at the airport. A security guard turned me back. Never before had I been so happy to be pushed aside by the law.

I waited at the curb for the shuttle bus. The wind was really blowing. It was that end-of-summer wind that is crisp and already carries the smell of the coming autumn, and the happiness wells up inside you because its all starting again. I stood on the bus, watching the terminals drift past, thepeople coming and going. I got off at the Marine Air Terminal, where you catch the charters. I went into the coffee shop and bought a Diet Coke. The building was empty, a few pilots sitting around drinking coffee. I had two hours to kill. I went out the side door and stood on the blacktop. Carts loaded with luggage went by. I walked across the road and climbed a retaining wall and found myself on a strip of grass that dropped off into Flushing Bay. The city was across the water. I could see the Whitestone Bridge and the Throgs Neck Bridge and the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge and the Triborough Bridge and the World Trade Center and the Empire State Building and the Citicorp building spread beneath crystalline skies.

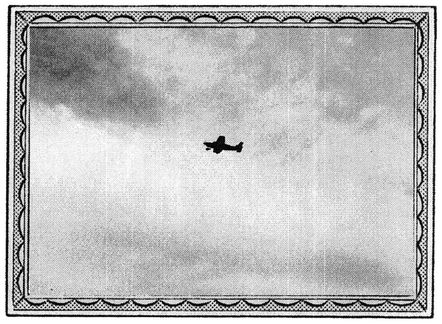

I lay down on the grass. I fell asleep. When I woke, the city was dazzling. It was as if it had been protecting me as I slept. I climbed over the wall and ran across the road to the terminal. My family was waiting. We walked to the runway and got onto the plane, a six-seat Cessna. The pilot threw some switches. The copilot said, Here we go. We raced down the runway and the nose went up and then the city was far below. We climbed into the clouds. The plane started to shake. The turbulence went from bad to worse. We were being tossed. It seemed as if the engines would tear off and the wings fall away and the fuselage cartwheel across the sky. This is the story of the family, I thought. This is the only family you have. This is the family in its mischief and its turbulence. This is the family until the family shatters and the pieces assemble themselves into other families. The pilot said, Roger, and we started to ascend. The plane banked hard to the east and was gone into the redness of the morning sun.

Cumberland Packing, the company that manufactures SweetN Low, occupies a boxy building across the street from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It sits amid the factories of Fort Greene, the last of the citys vanishing industrial base. The neighborhood is ringed by housing projects, dark windows looking out on the long skies over Williamsburg,.

In the summer of 2003, I drove to the factory to talk to my uncle Marvin, the president of the company. I had not seen much of him since my grandmother died. I gave my name at the door and was told to go around the side of the building, where my uncle was waiting.

To me, Marvin is always forty-five, blond, thin-hipped, and handsome, the kind of uncle who fixes things. When I was a kid, he took me on tours of the plant and had an ID made that showed my face in front of Cumberlands pink musical logo. He always had the newest gadgets and the biggest televisions. When he was a block from his car, hed press a button and the trunk would pop open. It was a convertible. I would sit in back as the storefronts of Brooklyn whistled by. Even into his sixties, Marvin was as peppy as a camp counsellor. Now, as I shook his hand andfollowed him inside, he seemed slower and sadder. He had a tremor in his voice and a shuffle in his step. Uncle Marvelous had gotten old! Its like this: young, young, young, young, young, OLD. Like the sun going down and down and down and bang, youre in the dark. It reminded me of something a journeyman baseball player once told me: Some guys go on and on, but other guys just fall off the table.

Marvin led me to his office. Its cramped, with the kind of drop ceiling you can fling pencils into. One wall is covered with photographs. By following these, you can watch Marvin ageface fill out, eyes deepen, children arrive. Some of the pictures go back to the 1950SMarvin in sepia tone, trim and tan, like a memory of Coney Island. He smiles in others, puts his arm around his wife, my beautiful aunt Barbara, or holds his kids on his back. None of the pictures was taken less than five or ten years ago, maybe when the scandal broke. Its as if he just shut off the camera and stopped recording. Most were taken on vacation, tropical beaches on Caribbean islandsthe triumph of the Jews, across the Jordan at last. My family had been along on some of these trips, but there was no hint of uswhy should there have been? It made me blanch to see the familiar settings with his sister Ellen and her issue so neatly excised.

Marvin wore a sleeveless fleece coatan alpine wife-beater or a muscle fleeceover an Izod shirt. His face was florid, as if one of those Caribbean tans had recurred like a fever. He said he had been prescribed a pill for failing memory, but told me he forgets to take it. He does remember that he forgets, which struck me as suspicious. An aquarium is built into one of his walls. It was once a saltwater tank, schools of tropical fish as gaudy as muscle cars amid a world of colored gravel and faux seaweed, a vibrant seascape that has degraded into an acid pond.

The fish died in the course of a single season some years ago, one of those strange kills that can decimate a closed system. I learned about it while reading the court papers. (A defense attorney wanted to know why Marvin had asked Cumberlands controller and chief financial officer, Gil Mederos, to clean out the tank.) Unfortunately, yes, there was one incident where there were saltwater fish, which are very delicate, and allthe fish were dying, Marvin testified. I felt so terrible. I remember telling Gil to cover the tank so I couldnt see the fish die.