Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Acknowledgments

Writing this book would not have been possible without the help of many people. First, I want to thank Alec Wilkinson, who is just about the best guy I know. Also, Ian Frazier, from whom I learned that serious people can be funny, funny people can be serious. And Sara Barret, David Lipsky, Jim Albrecht, C. S. Ledbetter III, Helen Thorpe, Melissa Roth, Todd Clark, Ralph and Renee Blumenthal, Debra Eisenstadt, Tad Floridis, Julie Bauer, Bill Brenner, Morris Liebman, Mark Varouxakis, Dennis Cohn, Brendan Lemon, Chris Knutsen, and my grandparents Benjamin and Betty Eisenstadt. I also want to acknowledge The New Yorker as it was when I got out of college, where, given a job as a messenger, I began pestering everyone with everything I had ever written. I especially want to thank those editors who gave me my first chance, Bob Gottlieb and Chip McGrath. I also owe a special debt to Jann Wenner, who brought me to Rolling Stone, where he has been less employer than friend, a patron who has given me so many opportunities. Also at Rolling Stone thanks to Bob Love, Sid Holt, Tobias Perse, Tom Conroy, and Will Dana. At Simon & Schuster I want to thank Dominick Anfuso and Ana DeBevoise. I am also grateful to Jessica Tuchinsky, at Creative Artists, who has become a good friend. And then my agent, Andrew Wylie, who is like Reggie was with the Yanksthe straw that stirs the drink. Also at the Wylie Agency I want to thank Jeff Posternak.

And, of course, Jessica Medoff, the one who is awakened when I have a dumb idea in the middle of the night, without whose support and insight I would not have finished this book.

Mostly I want to thank my parents, the Herb and Ellen of my best stories; my sister, Sharon Levin, and my brother-in-law, Bill Levin; my brother, Steven Cohen, and his wife, Lisa Melmed. And also down in North Miami Beach, the true promised land of the Jews, I want to thank my grandma Esther, thank her and say, No, Grandma, dont send a brisket. We have plenty of food here in New York.

F OR MY MOTHER AND FATHER

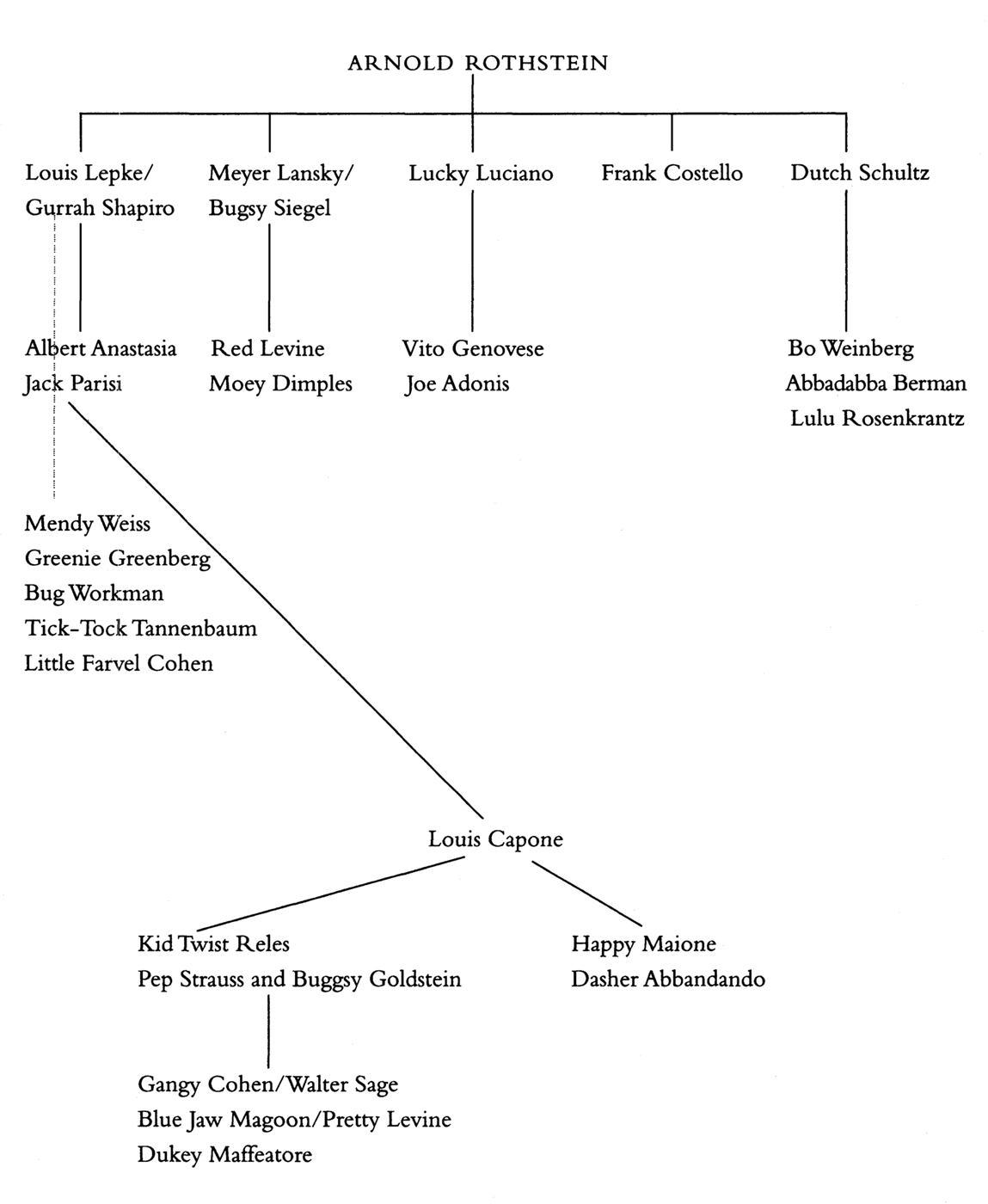

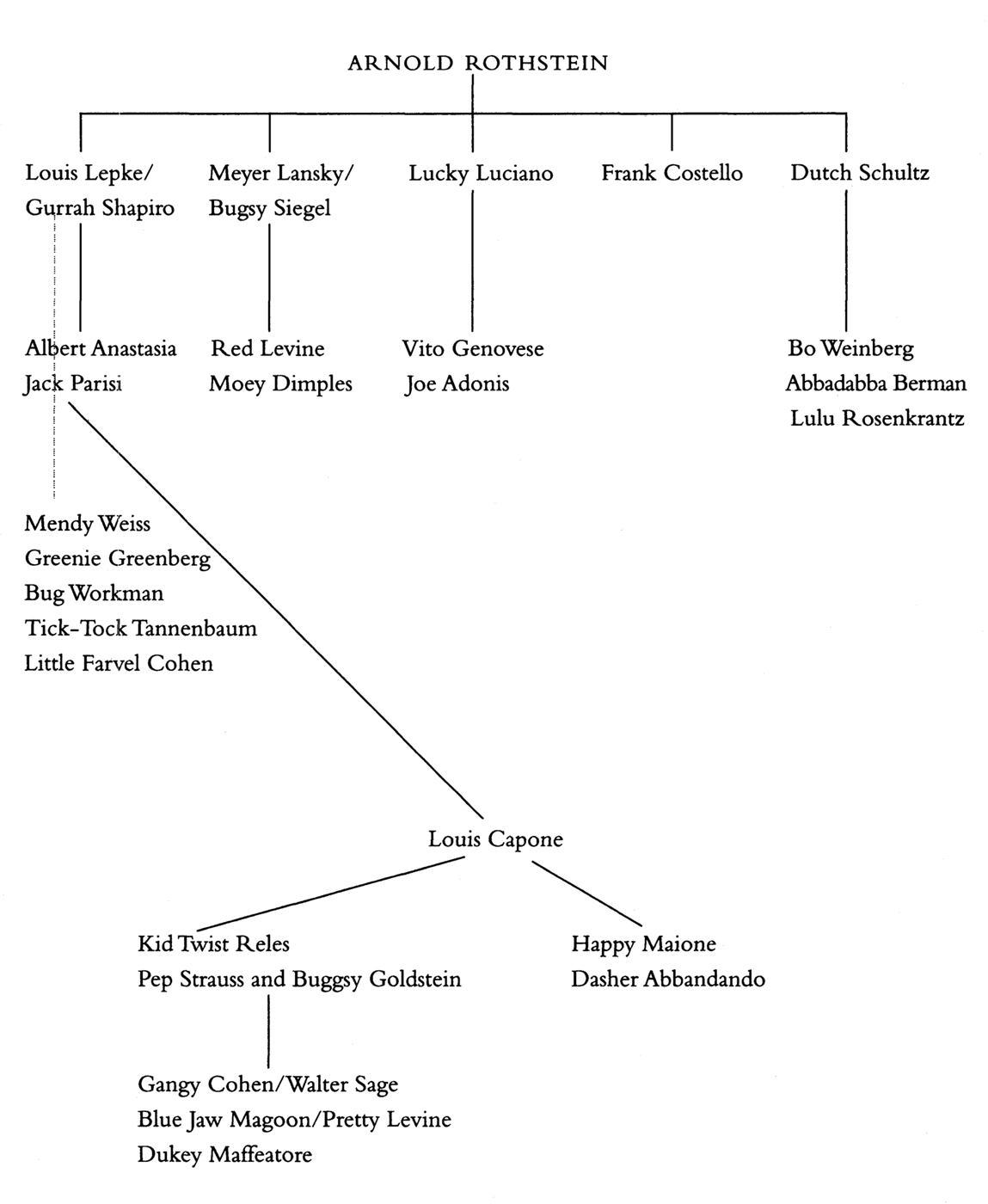

Arnolds Boys

The criminal progeny that grew out of Arnold Rothsteins underworld empire.

Nate n Als

THEY ARRIVE IN German and Italian sports cars. They double-park and discard the ticket. They come through the door of Nate n Als, a delicatessen in Beverly Hills, they come in from the glare of Rodeo Drive expecting friendly faces. They are not disappointed. They float in on Italian-made shoes. They jam the aisles, fill the air, talk pseudo-Yiddish. They ask for the pickles, the ketchup, the herring, and they never say please. Its always gimme, gimme, gimme.

Cmon, you heard Asher, says Herbie, folding his arms. Give em the herring. Asher gets the herring, lays it on his bagel, and never says thank you. Its okay. Its understood. There are lots of things Asher never says.

They sit each morning at the same booth in back of the restaurant. They look over crowded tables and booths, over mingling bigwigs and hustling waiters, over the cigar case, where toothpicks and mints can be had for free. They blink in the half-light known to all true delis, where every morning is the same morning. They sit among Jews who have moved from the EastBaltimore, Chicago, Brooklynand are now looking for something that got lost on the way west. They arrive at the hour agreed on the day before. Nine A.M. tomorrow, Sid had said, tapping his watch. Last to come, pays. Agreed? Heads nod. Agreed.

Today, Sid is the last to come. Sid will pay. Sid is a man of his word. He follows the rules. Especially when theyre my rules, he says, sliding into the booth. A man who breaks his own rules is no man at all.

Sid is a few inches under six feet tall and broad shouldered and burly, but size is not the first thing about him you notice. The first thing you notice are his eyes, which are full of mischief. Good eyes see the present and the past right at the same time, he says.

Sid has good eyes. Over the last several decades he has moved west with the country, from New York to Los Angeles. He has passed time at real estate conventions in the Midwest, drink in hand, corn and rye ripening all around. He has been to seminars, talked PTA, the future of the Rust Belt, computers, the explosion of the Southwest, the Internet. Still, in all these years, in all the houses with all the women, he never took his eyes off Bensonhurst, the neighborhood in Brooklyn where he came of age fifty years ago. Wherever he goes he surrounds himself with people who remind him in some vague way of those kids who formed his world in Brooklyn, where every son was an immigrants son, every dream the pipe dream of an immigrants son. In Los Angeles, where so many of his boyhood friends have also landed, he runs with the old crowd. Hello, fellas, he says, reaching for a menu. Happy to see everyone looking so happy.

Sid is a millionaire. He was in real estate. He sold his company. He says being from Brooklyn is a full-time job. When Sid talks, its in a high singsong that is pleasantly at odds with his frame. I see Im the last through the door, he says, motioning for a waitress. Guess I have to pay. Well, okay. Dont be shy, boys. Eat up. Im loaded.

They grunt in acknowledgment. Theyre lost in their food: Asher and his egg-white omelet, runny and covered in ketchup; Herbie and his bagel, light toast, light schmere; Larry picking at Ashers egg-white omelet, runny and covered in ketchup. I want a bagel and a whitefish, Sid tells the waitress. As he hands her the menu, he says, Tell the counterman to gouge out the eyes. I dont want breakfast looking at me.

Hey, Asher, you trying to hide your eggs from me? asks Larry, looking at Ashers plate. Whats with all the ketchup?

Shut up, says Asher. No one invited you.

A breed of such men thrive in Los Angeles, brokers, lawyers, entertainers, entertaining lawyers, promoters, moguls, former furriers, distributors, importers, exporters, self-promoters, men of leisure. They fled Brooklyn thirty-five, forty years ago and have shed as many outward signs of their heritage as would be shed, yet still retain something of the old world, a final, fleeting glimpse of what their fathers must have been. Their faces are concentrated, their talk full of warnings, premonitions of things to come, of time repeating itself, of good men stripped of all worldly goods and left to fight again with nothing but instinct. Every time he enters a room, Asher notes where each man stands, who poses the biggest threat, and who, if necessary, hell take out first. This is the stuff Im thinking about all the time, he says, wiping his hands. For me, its just like a crossword puzzle.

On those mornings when the gang is in high form, when the stories come fast as tracks on a CD, they pull Nate n Als off into a swamp of time, where old Brooklyn comes face-to-face with modern Los Angeles. On such occasions, the group is an attraction to those who fill the outlying booths, the regular clientele of Nate n Als, who watch the gang as if theyre watching mimes on stage, reading meaning in each gesture, seeing in them everything from how wealth is wasted on the uncouth to the last of a vanishing breed, whose very dialect, a thick Brooklynese, exists nowhere but in such storytelling, backward-looking circles. Theyre trying to teach my grandkid Spanish in school, says Asher, yielding his plate to Larry. What the hell? If he needs to learn anything, its Yiddish. The language of my people is dying.

Next page