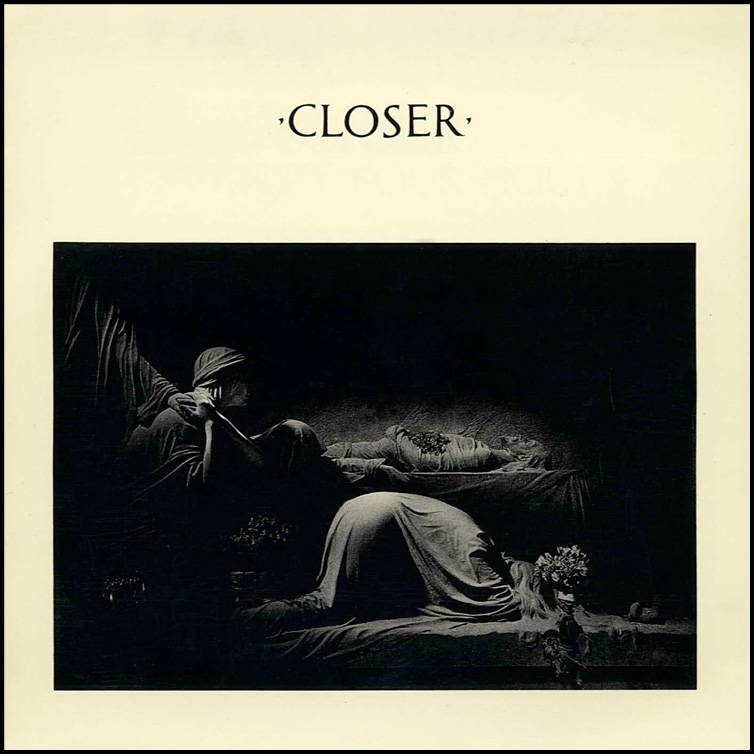

Closer by Joy Division

Dave Simpsons first ever gig was a painful experience. But it opened his eyes to Joy Division, whose second album he still considers the saddest, most beautiful music ever made

W hen I was still at school, I finished my Saturday job a couple of hours early to attend the Futurama festival in Leeds, headlined by Johnny Rottens PiL, my first-ever gig. My mate and I had our photos taken in Woolies to put on the ticket. When we got there, punks sniffed glue outside while old ladies passed by, shrieking Look at their hair!. I wore an iron-on Sid Vicious T-shirt. Everyone seemed much older and more knowing. We felt out of our depth and terrified.

Soon afterwards, Tony Wilson introduced the awesome Joy Division. I remember singer Ian Curtiss hypnotically twitchy dancing and the way he seemed to be gazing over us at something troubling in the distance. Every time the crowd surged forward a skinheads shoulder connected with my chin. By the end, I was in urgent need of a dentist but everything Id previously thought about music had been turned on its head: it could be more than entertainment, more powerful than punk.

I soon bought the Transmission single and then Unknown Pleasures, where Joy Divisions raw power had been sculpted into science-fiction landscapes, with whirring lift shafts and slamming doors, by whizzkid producer Martin Hannett. My Dad had died when I was young, and Id always been susceptible to songs with references to mortality such as Terry Jackss Seasons in the Sun and the Shangri-Las The Leader of the Pack both made-up tales; there was something more real and troubling about Joy Divisions New Dawn Fades. What kind of 22-year old writes lyrics such as a loaded gun, wont set you free?

By the time their second album, Closer, was released only a few months later, Curtis had taken his own life. The clues were on the record, in Colonys a cry for help, a hint of anaesthesia/ The sound from broken homes, we used to always meet here and 24 Hours Destiny unfolded, I watched it slip away. It wasnt until much later via Deborah Curtiss book and the Control film that we were allowed the full, tragic details of Curtiss tailspin into worsening epilepsy, prescription drug-contributed depression and domestic turmoil. The Manchester bands hurtling journey had taken them from Warsaw a proto-punk band whod played Lou Reed covers and sported feather cuts and embarrassing moustaches to 1980s stunning final album inside three years.

Back then, music was developing at a fast pace disco towards rap and hip-hop; funk and reggae towards world music; punk into post-punk. Closer was a quantum leap from Unknown Pleasures, and sounded unlike anything else.

Guitar tracks such as Colony and A Means to an End sounded angular, brutal and unforgiving, almost chilling in their terrifying beauty. But then the deceptively perky Isolation was mutated disco, which pointed the way towards electro-pop and the surviving members regroup as New Order. 24 Hours, where Peter Hooks mournful bass intro leads into a guitar-raging whirlpool, is still the definitive Joy Division anthem.

Then theres the spectral serenity of the synthesiser tracks, truly emotional music made with machines. The whiplash drumbeat and haunting, sub-bass shadows of Heart and Soul; the almost classical serenity of the piano-led, funereal The Eternal; the awesome Decades, Curtis gazing sorrowfully at human suffering and warfares doors of hells darker chambers, burdened by insights and events far beyond his years and his voice almost ghostly, a one-time punk with a new, Frank Sinatra-like croon.

It took three or four plays to fully hit home. But I can still remember an open window, the sun streaming on to my Fidelity UA4 stereo and a thought hitting me then that remains unchanged 31 years later: I love this album more then any music ever. For me, Closer contains the saddest, most beautiful music ever made.

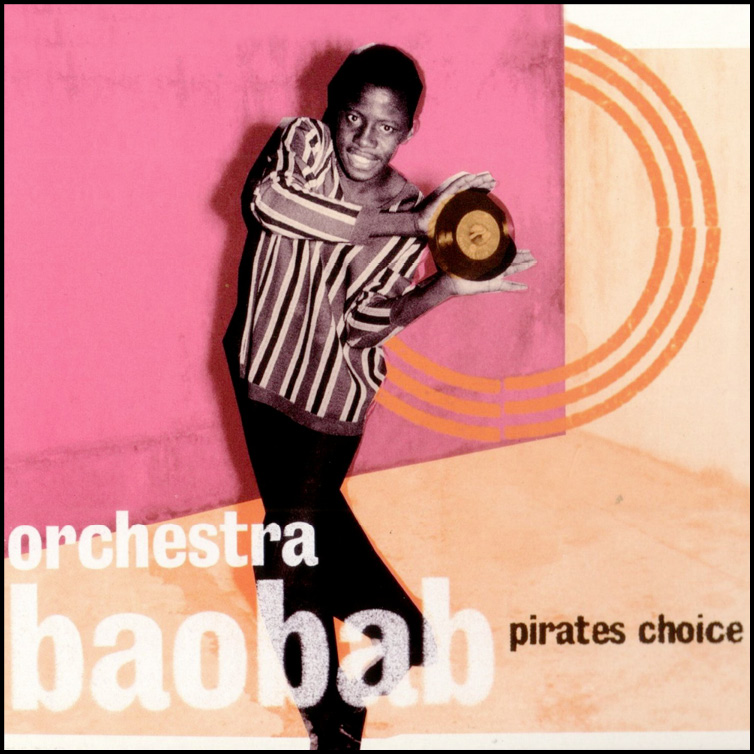

Pirates Choice by Orchestra Baobab

Caspar Llewellyn Smith marvels at the many historical tales told by this Senegalese band. But he marvels even more at their Cuban-influenced music

I t could feel lame to start any paean to a favourite record with a claim for its significance; it makes it sound dry, academic, removed from the emotions it engages. And yet the story of Pirates Choice bears re-telling, and what Ive taken from it over the years is bound up in its multiple histories. This was an album recorded in 1982, but only released in the UK seven years later, when it helped kickstart a new-found fascination among certain western listeners with world music. The band by that point had split up: their music deemed increasingly pass in Senegal itself, where once theyd been seen as harbingers of a new sound and style. But theres more than simply that: this seems to me to be a tale that reaches back much further in time, and crisscrosses the oceans more than twice over.

In Rumba on the River, an account of the popular music of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo, Gary Stewart describes the process by which Cuban son came to be the sound of this vast patch of Africa: as well as the most grotesque exploitation, colonialists brought to the country the wooden phonograph, and of the records available from the early 30s onwards mostly on the GV label, a subsidiary of HMV the most popular by far were Cuban in origin, by acts such as Don Azpiaz and his Havana Casino Orchestra. Now, was the appeal of that music rooted in a deep appreciation of where it had first originated, centuries back? African rhythms exported on slave ships echoed from the grooves of 78 rpm records and crackling radio loudspeakers, Stewart writes. Africans in the two Congos embraced them like a kidnapped offspring suddenly released from captivity.

I cant get enough of that sort of thing: as someone whos no musicologist, to read it felt like a flash of lightning had illuminated the fog of history. And while I appreciate that this is meant to be a review of a record, not a book, heres another of the details that I find so fascinating in Stewarts study: while the confluence at Stanley Pool of different musical influences recalled the miscegenation of styles in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, jazz evolved on the pianos, brass and woodwinds of Americas dominant European culture, whereas Congolese music embraced the guitar partly because pianos werent suited to the tropical humidity on the banks of the Congo, but mostly because the guitar sounded closest to the lutes and likembes of traditional African music.

Its the smokey guitar of Barthelemy Attiso that invites you into Pirates Choice, as if to say theres a late-night story to tell here. That Cuban and Cuban-influenced Congolese music reached Senegal in the middle decades of the last century, and so it is that when I play this record to people to whom this is terra incognita, they sometimes struggle to locate its origins and think it sounds as much like the work of the Buena Vista Social Club as it does African. So its partly this tale that the record relates, but there are other influences there, too; divining all these connections is at least part of what makes it so magical to me.

Wolfish whistles, timbales and the languid tenor sax of Issa Cissoko join the guitar on that opening track of the record, Utru Horas, and then we hear the voice of Rudy Gomis. He sings in Portuguese creole, and even Googling the song now, Im no wiser as to what it is that hes singing about. The point is, its never mattered: the reverie created by the music is so delicious in itself, the atmosphere that of an after-hours club, the bottle almost empty, a couple swaying on the dancefloor. Time slows.

Next page