YURI OLESHA (18991960), the son of an impoverished land-owner who spent his days playing cards, grew up in Odessa, a lively multicultural city whose literary scene also included Isaac Babel. Olesha made his name as a writer with Three Fat Men, a proletarian fairy tale, and had an even greater success with Envy in 1927. Soon, however, the ambiguous nature of the novellas depiction of the new revolutionary era led to complaints from high, followed by the collapse of his career and the disappearance of his books. In 1934, Olesha addressed the First Congress of Soviet Writers, arguing that a writer should be allowed the freedom to choose his own style and themes. For the rest of his life he wrote very little. A memoir of his youth, No Day Without a Line, appeared posthumously.

KEN KALFUS s most recent book is a novel, The Commissariat of Enlightenment. He is also the author of two short story collections, Thirst and Pu-239 and Other Russian Fantasies.

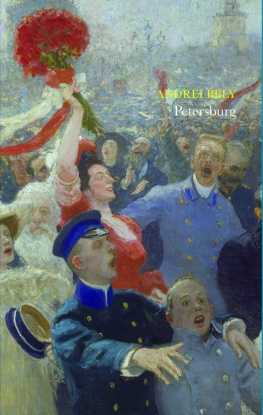

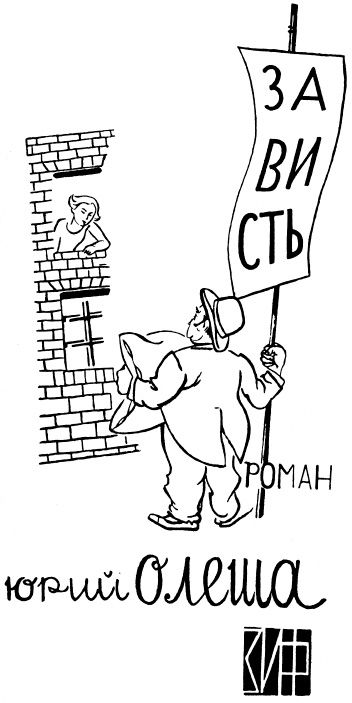

ENVY

YURI OLESHA

Translated from the Russian by

MARIAN SCHWARTZ

Introduction by

KEN KALFUS

Illustrations by

NATAN ALTMAN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Y URI OLESHAS short novel Envy first appeared in the Soviet literary magazine Red Virgin Soil in the latter part of 1927, a perilous season in the history of the socialist republic. As Stalin consolidated power, the Party-controlled press warned of military intervention by Great Britain and its anti-Communist allies. The liberal New Economic Program was terminated, diminishing the supplies of produce and goods to the cities. The regime intensified its propaganda efforts. Bolshevik critics lashed out at the artistic avant-garde, which had flourished earlier in the decade. Late that autumn Stalin would crush the opposition at the 15th Party Congress and expel Trotsky from the Partyand fire the editor of Red Virgin Soil, Aleksandr Voronsky. After that, creative momentum would keep nonconformist artists in heedless motion for a few more years until they ran smack, sometimes fatally, into the wall of Party-dictated socialist realism.

We can imagine that summer of 1927 as having been very fine in Moscow, as bright and breezy as the day of the soccer match that occupies several chapters at the novels conclusion. Food and other necessities were in short supply, but privations might have weighed gently on the shoulders of an up-and-coming, nondoctrinaire, twenty-eight-year-old writer on the staff of the Whistle, the widely read newspaper of the Railway Workers Union. It was an illustrious staff: Olesha shared pages with Mikhail Bulgakov and his fellow Odessans Isaac Babel, Ilya Ilf, and Yevgeny Petrov. If they had managed to ignore day-to-day politics, they might have thought the Revolution could still tolerate satire and literary adventure.

In his work at the Whistle, Olesha found plenty of satirical targets among the low-level officials he held responsible for the quotidian incompetencies and indignities that plagued Soviet life (without implicating Party leaders, who were presumed to be struggling against them as well). He turned the familiarly knavish caricature on its head when he created Envys Andrei Babichev, the trade director of the Food Industry Trust, as a good-natured, happily corpulent, go-getting apparatchik. Andrei has devised a thirty-five-kopek sausage and intends to build a giant communal dining hall, to be called the Two Bits. These laughably materialistic projects, echoing Bolshevik promises reported in papers like the Whistle, become facets in a many-sided farce that obliquely sends up early Soviet mores and ambitions while speaking beyond Soviet borders on behalf of the individual conscience in a mechanizing, incorporating twentieth century.

Oleshas Andrei would be an unreservedly positive figure if his image were not mediated through the eyes of Nikolai Kavalerov, the spiteful young intellectual whom Andrei has rescued after finding him drunk in the street. The apparatchik has taken him back to his flat and generously installed him on the divan in his living room. From this vantage during the next several weeks, the wretched, self-loathing Nikolai observes Andreis gross habits and intimate human failingsmost damning of which is apparently the mole on his back. Nikolai bitterly envies Andreis professional success and mocks the optimism of the Revolution. His enmity is stoked by the insults he imagines Andrei would hurl at him if the blameless Andrei were in fact to insult him.

Nikolais black fantasies drive this novel, give it its avant-garde weirdness, and frustrate readers looking for a direct political interpretation. Envys most vivid scenes and dialogues dont actually occurNikolai invents them. For example when Andrei goes to a communal apartment house on an official visit, hes expelled by housewives angry at their domestic conditions. He leaves speechless. He has no imagination. Its Nikolai who derisively tells the reader (not Andrei) that Andrei should have used that moment to promote the Two Bits. He supplies Andreis putative and absurdly propagandistic exhortations:

You, young wife, you cook your husband soup. You sacrifice half your day to a puddle of soup! Were going to transform your puddles into shimmering seas, were going to ladle out cabbage soup by the ocean, pour kasha by the wheelbarrow, the blancmange is going to advance like a glacier! Listen, housewives, wait, this is what were promising you: the tile floor bathed in sunlight, the copper kettles burnished, the saucers lily-white, the milk as heavy as quicksilver, and the smells rising from the soup so heavenly theyll be the envy of the flowers on your tables.

Nikolai renders (through Olesha; through the well-tuned lyricism of translator Marian Schwartz) this radiant future more memorably than he does the grim present. Time and again we see and dont see the real Andrei; were confused by Nikolais sarcastic mutterings that distort what the trade director has done and said, inflating his grandeur as well as his six-pood carnality. The image of Andrei Babichev is deliberately refracted through the prism of propaganda and the newly Sovietized Russian language, meant to accommodate revolutionary politics and the new communal and mechanized way of life. The result brings to mind the fractured and reflected human figures within early-twentieth-century Russian paintings like Pavel Filonovs Victory over Eternity and Kasimir Malevichs pre-war cubist masterpiece, The Knife Grinder.

Olesha further disorients the reader once he introduces another character, Andreis subversive brother Ivan Babichev. Nikolai meets him after glimpsing his reflection in a mirror on the street, the kind of literary trick practiced by Nabokov (though executed here with not quite the same dexterity). Nikolai quickly identifies Ivan as my friend, teacher, and consolerhis secret sharer. Ivan is an alternate Nikolai in antiquated costume, most notably a bowler hat. Like his brother Andrei, his apparent form isnt necessarily consistent with reality. If Andreis character is defined by propagandistic bombast and Nikolais malice, Ivan exists within rumors and hearsay: hes a poet, a dreamer, an inventor of a robot, and a rabble-rouser who breaks up weddings and stalks his brother at official functions. The rumors say that hes been interrogated by the GPU.

Its Nikolais shiftlessness and his inability to adapt to the optimism of the new age that make him hate Andrei. Ivan is hardly more productive as a citizen, yet hes a malcontent with convictions, distinctly attached to a former way of life. He is said to tell the police that he leads an underground political movement whose goal is the preservation of pity, tenderness, pride, jealousy, lovein short, nearly all the emotions comprised by the soul of the man in the era now coming to a close. The figmental organization appears to be less oppositional than conservational: people like his friend Nikolai must be saved because they are the repositories of classic human emotions. In Nikolais case, the emotional essence is envy, the bane of the classless society.

Next page