Copyright 1997, 2007 by Craig Childs

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

The Little, Brown and Company name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: December 2007

ISBN: 978-0-316-02433-4

ALSO BY Craig Childs

House of Rain

The Way Out

The Desert Cries

Soul of Nowhere

The Secret Knowledge of Water

For

Jasper and Jaden

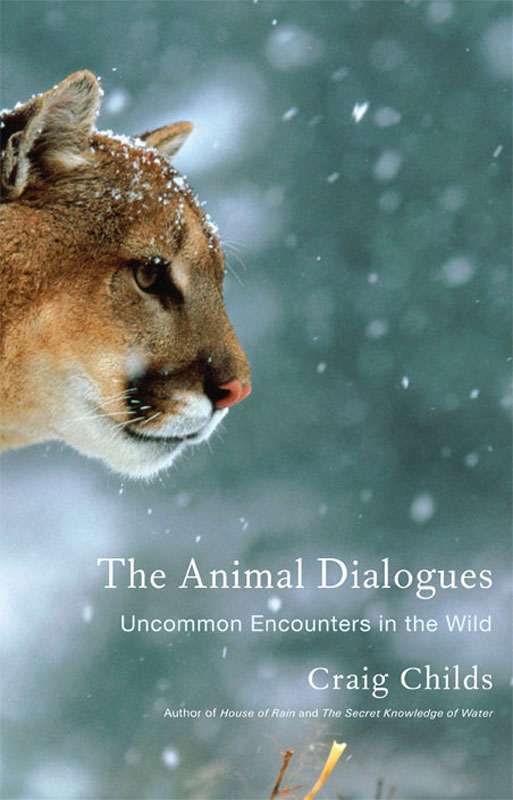

S ome of the stories in the following pages originally appeared in a book I wrote in 1997 called Crossing Paths. Other stories have been written since then. They need not be read in any particular sequence or all in one sitting. They are not in chronological order. I have hoped, in fact, that you, the reader, might come upon this book by accident, finding it on a desk, left open to a passage on mountain lions, or flipping its pages until you are caught in the stares of fifteen sorcerous ravens. This is how each story came to me: unexpectedly, halting my breath before I could draw it in. If you are one of those people who insist on reading books from left to right, I recommend a sip of clear water before starting each new chapter. Even better, I suggest that before you read the next story, you open your door and walk into the woods where only birds and spying raccoons might see you, or into a desert of lizards and jackrabbits, if that is what is at hand. Paw up the dirt and taste it on your lips. Drink out of a stream or from the lucid depths of a bedrock water hole. Return to your house, where this book waits on a table. Pull up a chair and see what other wild creature comes to speak with you.

GREAT BLUE HERON

I was very young when I woke before dawn and grabbed the small knapsack beside the bed. In it I placed a spiral notepad, a sharpened pencil, a paper bag containing breakfast, and a heavy thrift-store tape recorder with grossly oversized buttons. I walked outside, through the neighborhood, and at the edge of a field full of red-winged blackbirds, I took out the tape recorder. Their officious prattle lifted like shouts from the stock market floor. I pushed record and listened.

In time I moved on, recording birds in different trees, in other lots. I ate cold toast with careful bites. Writing things down: the time, the place, what the bird looked like. My penmanship was terrible, shaky, typical for elementary school. I wanted so badly to be able to write like an adult. Occasionally I would just make loops with the pencil so that it looked like cursive. I worked at the entries, putting the last letter or two of a word on the next line if it wouldnt fit. It was important, as important as anything, and I acted as if I knew what I was doing, as if I knew something about birds. Which I did not. I understood only that they flew and that they did it well. I would hold the pencil in my teeth and hum thoughtfully as I had seen the adults do.

With my tape recorder, I walked these fields fanning below the east side of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. So rarely was I awake at this time of the day that it felt like my birthday or Thanksgiving. I had not known that the sunrise was so lavish and that you could actually feel the color when it reached your face. I had a fantasy of running away to the woods, becoming a nomad and a hermit, but soon enough the sixty minutes of tape ran out. I returned home. There I ate breakfast a second time.

Not for decades would I hear of John James Audubon or Aldo Leopold or Ann Zwinger. In these decades I would grope into the land. I would be blatantly watched by grizzly bears and hummingbirds. I would blow dust from tracks and crawl on my stomach through forests to see the animal. My truck would be buried axle-deep in the sandpits of New Mexican back roads. I would become a river guide in the North American deserts and take young students from cities into the wilderness, teaching them how to smell for coyotes and how to let tarantulas walk over their hands. I would rope into canyons looking for all the fear and quiescence and exquisite forms that roil in the wilderness.

Now I go out walking. Sometimes for a hundred miles, circling mountain ranges or following canyons for weeks and months. More often it is a quarter mile in an afternoon, shuffling around the trees, looking for a soft place to sit. Out of habit, my eyes train on shapes and movements, and if I see any animal, it is invariably unexpected. I have no idea how proficient trackers do itchoosing their animal, then finding it. I choose a coyote and I get a very rainy day. I choose an elk and get a deer mouse. Then a mountain lion comes from behind while I am crouched, looking at its tracks.

To see the animal, you must first remain very still. You may have to huddle in the dark of a street culvert for three nights before the raccoon comes. You may have to sit naked on the tundra before the grizzly finds you. Or you will simply have to be there, driving the highway the moment that a caravan of unhurried red-backed salamanders passes from one side to the other. That is when you must leave your car and get on hands and knees in the roadway. Just be careful not to touch the salamanders, because the acid from your fingerprints will burn into their backs. When you encounter an animal, it may be as startling and quick as the buzz of a rattlesnake. Or you may have time to note the shift of wind and the daily motions of light.

Times that I have seen the animals have been like knife cuts in fabric. Through these stabs I could see a second world. There were stories of evolution and hunger and death. Cross sections of genetic histories and predator-prey relationships, of lives as cryptic as blood paths in snow. I have talked with those at the Division of Wildlife who know. I have rummaged through clutters of skulls and skeletons in a musty museum basement and read the reports of field biologists. But it is outside where the grip of the story lies.

It was at a guide house near the Colorado River in Arizona that I saw the great blue heron. We were cleaning gear at the end of a river-running trip. Open ice chests and tired people. Equipment was being moved with dry, cracked hands that bleed as they often do midway through the season. The man behind me told me to look up, and I pulled my head out of an ice chest. Sweeping into view twenty feet above was a great blue heron. It had the monstrous wingspan of a flying dinosaur, its snakelike neck stretched ahead, its long legs trailing behind. As it reached the telephone pole directly over our heads, its wings changed. Feathers spread with the fullness of a parachute. They stalled the air, these domed wings suddenly occupying more space than both of our bodies combined. With limber figure-skating grace, it landed on the flat of the pole top. The wings remained out for a moment, the heron teetering for balance. Then they closed.

Jesus, look at that bird, said the person behind me. And, Jesus, I looked at it. Head to toe, it was nearly five feet tall, a subtle steel blue that tricks the eyes. It surveyed the landscape of mobile homes and river equipment below. From our vantage point we could see straight up its body. Its head was colorful, with contrasting grays and blues and the yellow of its saber beak. Balanced on the long neck, the head moved independently of the body. Head motions were a language in themselves, with the weight of the back of its skull balancing the lightness of its beak.