Celan Paul - Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan

Here you can read online Celan Paul - Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Princeton, N.J, year: 1999, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

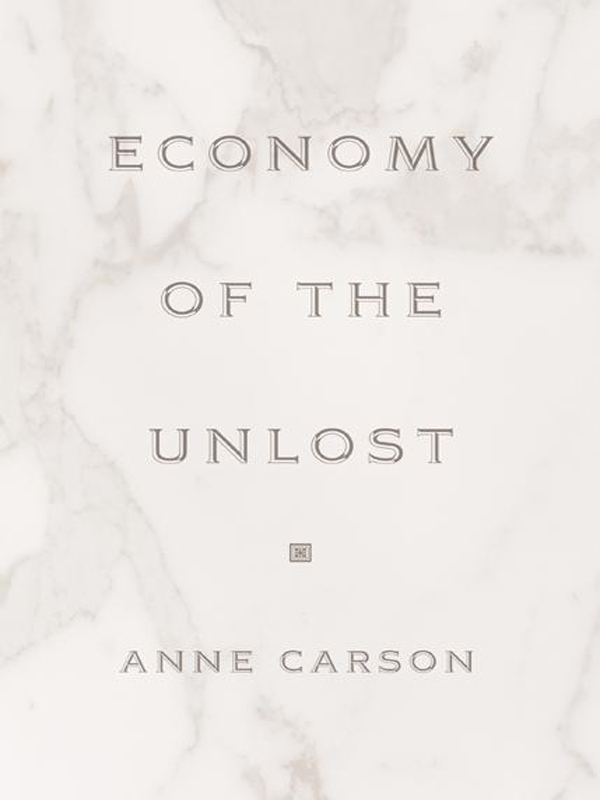

- Book:Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1999

- City:Princeton, N.J

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The ancient Greek lyric poet Simonides of Keos was the first poet in the Western tradition to take money for poetic composition. From this starting point, Anne Carson launches an exploration, poetic in its own right, of the idea of poetic economy. She offers a reading of certain of Simonides texts and aligns these with writings of the modern Romanian poet Paul Celan, a Jew and survivor of the Holocaust, whose economies of language are notorious. Asking such questions as, What is lost when words are wasted? and Who profits when words are saved? Carson reveals the two poets striking commonalities.

In Carsons view Simonides and Celan share a similar mentality or disposition toward the world, language and the work of the poet. Economy of the Unlost begins by showing how each of the two poets stands in a state of alienation between two worlds. In Simonides case, the gift economy of fifth-century b.c. Greece was giving way to one based on money and commodities, while Celans life spanned pre- and post-Holocaust worlds, and he himself, writing in German, became estranged from his native language. Carson goes on to consider various aspects of the two poets techniques for coming to grips with the invisible through the visible world. A focus on the genre of the epitaph grants insights into the kinds of exchange the poets envision between the living and the dead. Assessing the impact on Simonidean composition of the material fact of inscription on stone, Carson suggests that a need for brevity influenced the exactitude and clarity of Simonides style, and proposes a comparison with Celans interest in the negative design of printmaking: both poets, though in different ways, employ a kind of negative image making, cutting away all that is superfluous. This books juxtaposition of the two poets illuminates their differences--Simonides fundamental faith in the power of the word, Celans ultimate despair--as well as their similarities; it provides fertile ground for the virtuosic interplay of Carsons scholarship and her poetic sensibility.

Celan Paul: author's other books

Who wrote Economy of the unlost : reading Simonides of Keos with Paul Celan? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.