CHAPTER ONE

COUP CULTURE

Between the 1960s and 1980s, any car manufacturer with ambitions to become a player in the prestige market in Germany had to include a big luxury coup in its range. It is tempting to trace the tradition all the way back to the 1930s and the beginnings of Germanys Autobahn network, which allowed such cars to be enjoyed to the full. It is equally tempting to trace the style back to the elegant and luxurious French coachwork designs of the 1930s, which set the style for the whole of European high society. However, for the purposes of this book, there is no need to go back further than 1951 and the International Automobile Exhibition held at Frankfurt that April.

The Frankfurt show was a very important event for the German automotive industry. A significant number of companies had been put out of action by the six years of war that had ended in 1945. Many never recovered, but a handful did claw their way back to viability during the later 1940s. The country had been divided in two and even the average German in the West was unable to afford a car of any kind in those years. However, between 1947 and 1949 the car makers and accessory manufacturers did show their wares at the annual trade fair in Hanover, highlighting what Germany could offer overseas buyers. Even though the cars on show were mainly out of their reach, the event was always a major attraction for local visitors, who would visit to dream.

The BMW 327 Coup of the 1930s was a strikingly beautiful car, and is seen today as an ancestor of the big coups from the 1960s and 1970s.

By the end of the 1940s, some semblance of order was beginning to return to the West German car market. Mercedes-Benz was building some extremely credible middle-class machines and was poised to re-enter the sports-car and prestige markets. BMW, by contrast, was still working on new designs, and by 1950 was testing prototypes of a little rear-engined two-seater, known as the BMW 331 and clearly inspired by the Fiat 500. By that stage, however, West Germany was preparing to move on. Planned for April 1951 was a brand-new event a car show to be held in the halls of the trade-fair site in Frankfurt. Berlin, traditional host of the major annual motor show in Germany, also planned a revival of that event for that September. Although the Berlin event would be a last gasp and Frankfurt would take over as the major German show, it was clear that 1951 was going to be an important year.

For the German motor industry, Frankfurt 1951 acted as a call to arms. This was going to be an opportunity to show that it had left behind the problems of the war years and their aftermath. Here, they could show their latest wares or, at least, the models they hoped to get into production soon and demonstrate to the world that German engineering had undergone a renaissance.

The 1952 prototype coup by Autenrieth on the 501 chassis was strangely bulbous, in the fashion of the times.

Mercedes-Benz went all out to get its new six-cylinder 220 model ready for the show. BMW, meanwhile, had been looking at the possibility of producing other makers designs under licence. Their fallback option was the little 331 model, but this was apparently vetoed by Sales Director Hanns Grewenig. His view was that BMWs limited production capacity was better suited to a small-volume car with high profit margins than to a small car that would have to be built in high numbers in order to generate good profits. He must also have realized that, if Mercedes-Benz did launch a new prestige model at Frankfurt in 1951, it was going to make a fundamental difference to the German car market and to the way German cars were perceived abroad. BMW needed to develop a prestige model, and quickly.

BMW abandoned work on the 331 and threw all their resources into developing a prestige saloon. Time and development resources were saved by using a further development of the pre-war BMW 2-litre engine. Although the new 501 that was announced at the Frankfurt Show in April 1951 was too heavy to equal the performance of the Mercedes-Benz 220, introduced at the same time, its 2-litre engine nevertheless made it a credible entrant in West Germanys prestige saloon class.

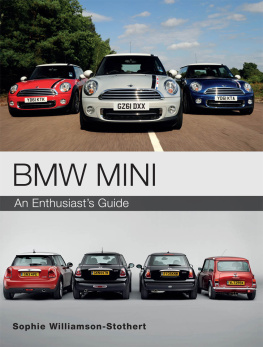

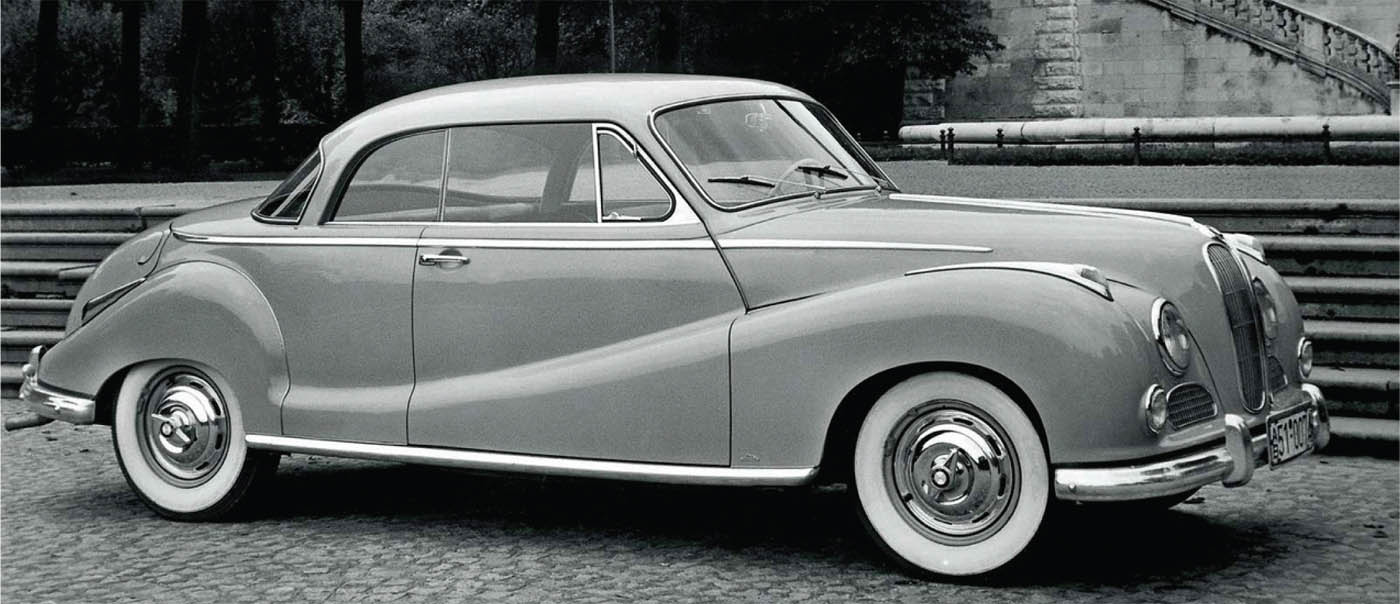

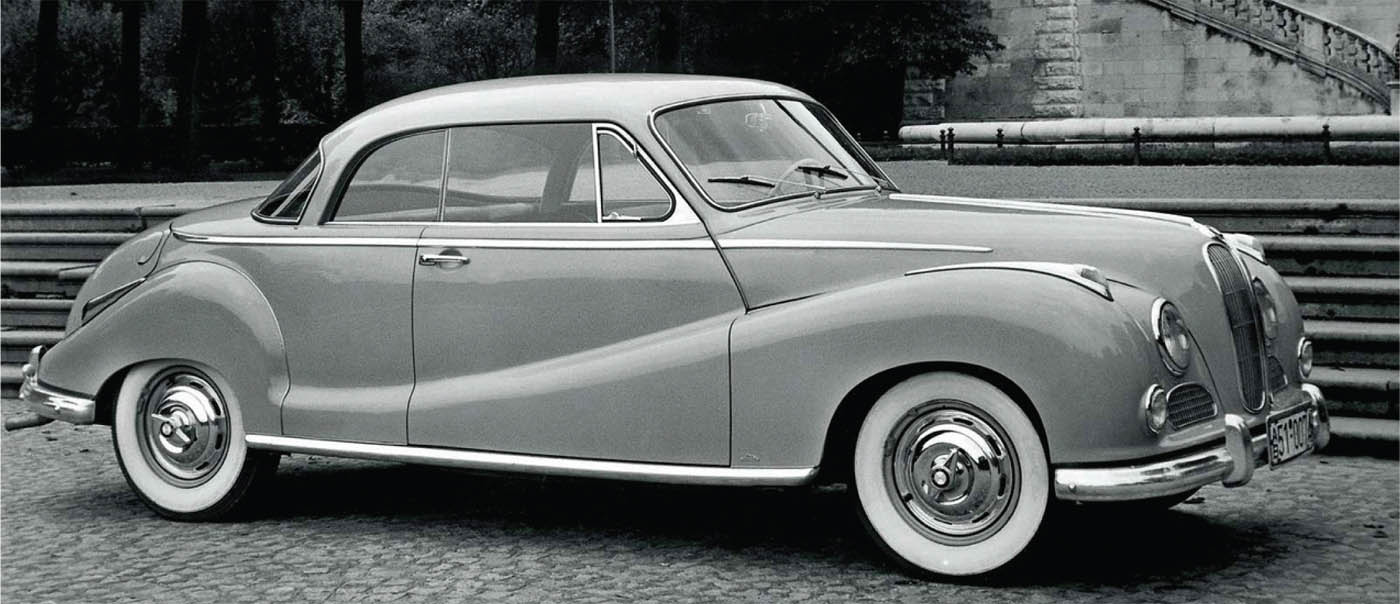

More commonly seen was the later Baur coup body, seen here on a 502 chassis.

The importance of announcing the new model at Frankfurt was obvious: this was BMWs first post-war car. In practice, it would not be available for purchase for another 18 months deliveries began in October 1952 but BMW had laid claim to a slice of the prestige coup market. Like Mercedes-Benz, BMW knew that that market would return. Lacking the resources to build their own coup bodies, they turned to coachbuilder Autenrieth in Darmstadt and were looking at that companys prototype coup for the 501 chassis during 1952. This coup, and from 1955 one by Baur, became available for special order alongside the saloons. As the original 501 chassis developed into a V8-engined 502 in 1954, so these coups and their cabriolet derivatives presented an attractive alternative to the established Mercedes-Benz six-cylinders.

The 503 Coup

Hanns Grewenig, still BMWs Sales Director, could see the potential of developing a distinctive grand tourer on the 501 and 502 chassis, and in 1954 he gained approval for such a car. Designed by Albrecht Goertz, with the encouragement of European car importer Max Hoffmann in the USA, the styling made deliberate reference to Italian coachwork, but remained determinedly Teutonic. It was ready to be shown at the 1955 Frankfurt Motor Show, which now occupied the autumn slot that had originally been reserved for the Berlin event.

Based on a wide-track 502 chassis and featuring the most powerful 3.2-litre version of the V8 engine, with 160PS, the new model came as either coup or cabriolet. Despite aluminium panels, it was no lighter than the rather over-bodied saloons, but a top speed of 190km/h (118mph) made it faster than the rival Mercedes-Benz 220S coup and that gave it a special prestige of its own. Unfortunately, it was also nearly 40 per cent more expensive than the Mercedes, at 29,500 DM versus 21,200 DM, and that price premium proved a big hindrance to sales both at home and abroad. The 503 went on sale in May 1956, and production ended in March 1960. Just 412 cars 273 coups and 139 cabriolets had been built, and BMW had lost money on every one of them. The cost of building these cars by hand at a rate of around two a week was really more than BMW could absorb at a time when it did not have a big-selling volume car in production.

Nevertheless, the 503 had staked BMWs claim to a place in the prestige coup market at home in Germany and also in the wider European market and in the USA. In that sense, it was a vitally important model for the companys future. Although it was not immediately replaced BMW was going through a tricky period around 1960, and could not finance such loss-leading products the idea of a new big coup was never far from the thoughts of BMW management.

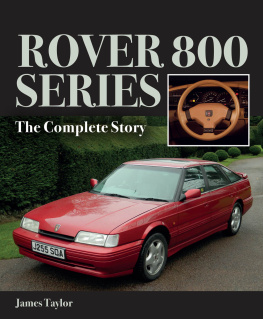

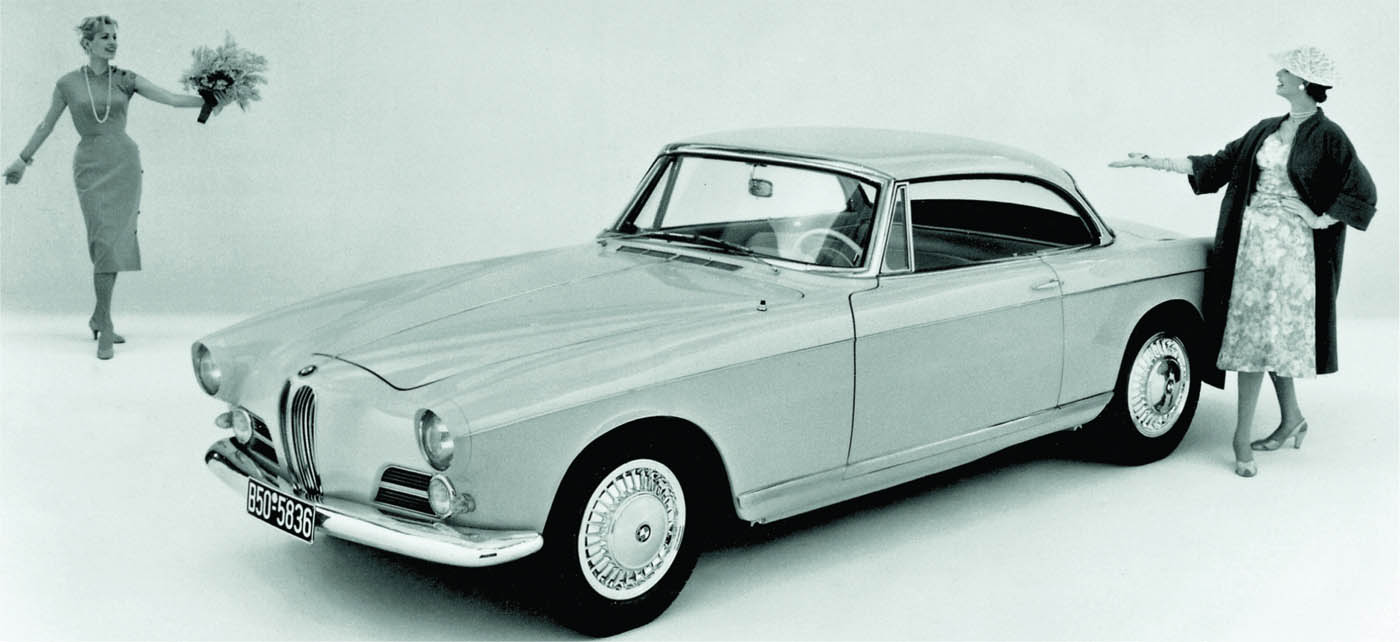

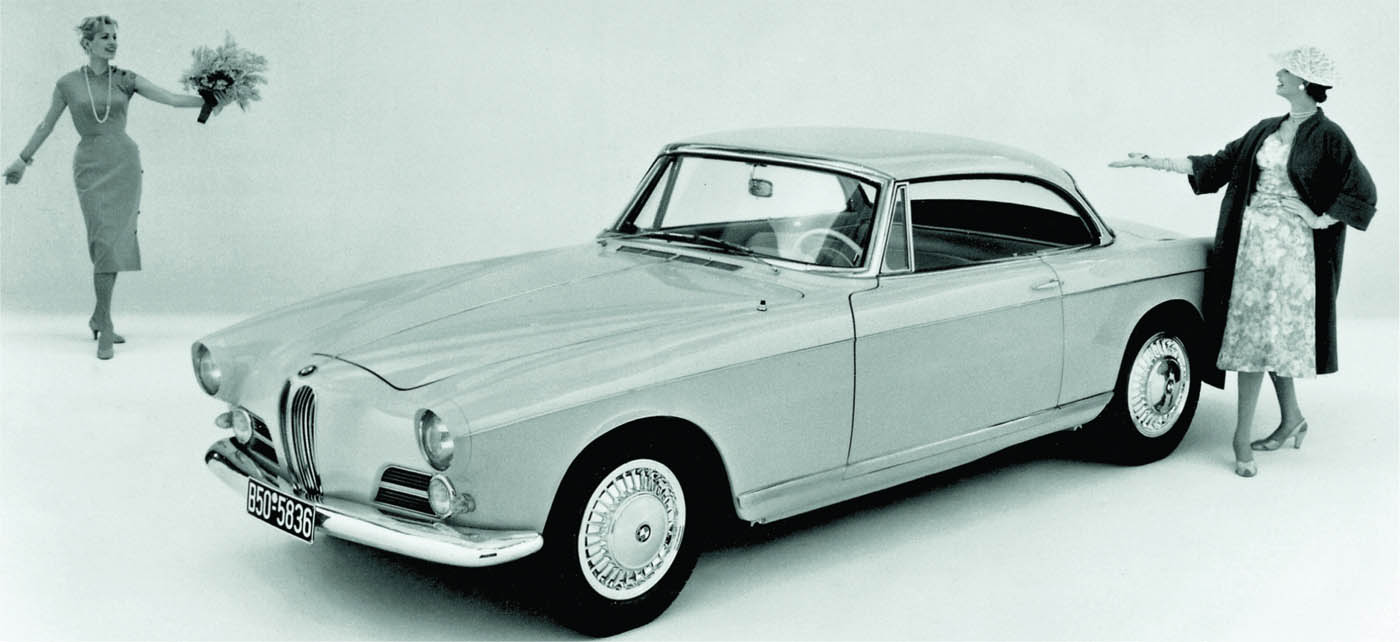

Neither of the earlier 1950s coup designs had much appeal outside Germany, so a special and more modern-looking body was drawn up for the 503 coup, with which BMW hoped to capture a slice of the big US market. This example has an interesting spoked style of wheel trim.