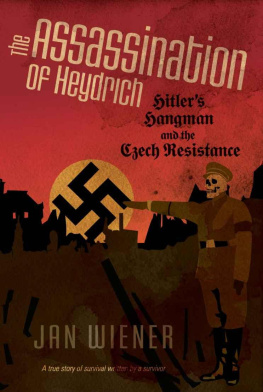

The Assassination of Heydrich

Hitlers Hangman

and the Czech Resistance

Jan Wiener

Foreword

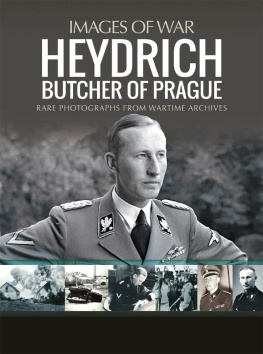

The name Reinhard Heydrich may not mean much to contemporary readers in this country. It is true that there are a number of people who remember his name and the fact that he was assassinated during World War II. Some people remember Lidice and the shock that was felt in the world when this village was totally destroyed in reprisal for Heydrichs death. But few people will know the atmosphere that prevailed in occupied Czechoslovakia, the fear and terror, during the period called the Heydrichiade.

This, then, is the story of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich by the Czech people. It has been pieced together years afterward from survivors and peripheral participants recollections, from various documents, and from Nazi records. I was only a peripheral participant, as I was forced to leave Prague after the occupation, but my storyaside from being fairly typical of the Czech refugeetouches the lives of some of the main characters in the resistance. I have included it as a frame of reference which the reader can perhaps identify with. It will also help to explain my knowledge of various activities and strategies employed by the resistance.

The issues at stake in this book are especially alive for the Czechs and Slovaks. Through a period of more than six hundred years the Czechs learned how to live as an oppressed minority and how to survive. In 1918 they were largely responsible for the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with its unjust minority polity.

In a small occupied country in which the population is defenseless and exposed to the harsh measures of the occupier, the desire to survive is enormous as is the fear of violent death. Some people when faced with decisions that involve their own safety become so overwhelmed by the will to survive and the fear of death that they do things which under normal conditions they would not do. Others are able to master their fears and to help and to fight back.

To these people I dedicate this book. Some of them for one night sheltered people who were marked by the Gestapo. Some gave food. Others knew but did not inform. Others, again, were active saboteurs and national avengers.

-- Jan Wiener

Lenox, Massachusetts

June 1969

The Invaders

Both of my parents were born in Bohemia, which became part of Czechoslovakia when it was created in 1918. They grew up, met, and married in Prague. After World War I they moved to Hamburg where, in 1920,1 was born. I lived among German people, went to school in Germany, and naturally learned to speak fluent German.

After Hitler came to power in 1933, pressures against Jews forced those of us who could manage to leave Germany to do so. We Wieners moved back to my parents native country, where my grandmother still lived. I went to school in Prague, learned the Czech language, and learned to love the country and the people who had given usand many other refugees asylum and a new home.

Czechoslovakia at that time was a country with a very liberal democratic political system, therefore a country in which it was good to live. My friends were Czech boys. Through my friends I became actively involved in the cause of Czechoslovakia. By the time of the first general mobilization of the Czech army in 1938 when I was seventeen, I had so identified with this small nation that of course I volunteered to help fight for its integrity.

I was sent, as an infantry soldier, to the Giant Mountains in the northeast sector, bordering Germany.

We all expected to be fighting Germany at any moment, but we were confident that England and France, with whom Czechoslovakia had a pact of mutual military assistance, would come to our aid when we were attacked. However, in September of 1938, Sir Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier formed the Munich Agreement with Mussolini and Hitler. Our borders, including the Sudetenland, were conceded by them to belong to Germany; Teschen was handed to the Poles; Czecho-Slovakia was hyphenated and declared two autonomous states. Besides crippling our transportation system, our economy, and shattering our national morale, this dismemberment made defense impossible as it took from us our fortified border mountains. The carving up of Czechoslovakia and the handing of our strategic territories to Hitler on a platter were supposed to appease his hunger. His demands were to end there; our sacrifice would bring peace in our time.

It is still deeply imprinted on my memory how we Czechoslovak boys, so eager, so primed to fight for our national existence, were sent home from the border. The appeasement of Hitlers appetite for territory lasted five and a half months. He violated the Munich Pactas he did all other agreements.

Shedding our uniforms reluctantly, the farm boys went back to their farms and others returned to jobs, while soldiers in the regular army had to sit around in barracks doing busywork. I returned to my schoolboy routine.

My father had left for Yugoslavia and my mother was anxious for me to follow him. I had my schoolboys free ticket to the theater once a week, I had sports, I had friends, and I had the Sokol.

The Sokol (which means Falcons, or Hawks) then was a national physical-training society to which many belonged. There was a Sokol gymnasium in each community to which the men and boys on mens nights and the women and girls on womens nights went to exercise. Here we also cemented friendships; we met and admired leading gymnasts of other communities during frequent exchange visits and social affairs.

I know of no comparable institution in other countries which so completely erased class lines: here the banker, the farmer, the butcher all appeared in their gym suits to take part. Needless to say, there was no occupational guarantee that any of these would look more handsome than the others; in Sokol each man earned his fellows esteem through personal ability. The Sokol was abolished by the Communist government in 1948. In 1956 it was, because of its popularity, reinstalled but under Communistic ideals.

I, my friends, my chemistry professor, and my mailman all spent many evenings each week at Sokol. It was here that political discussions would arise among the men; heads would be shaken, fists pounded. It was here that our natural leaders in any resistance would come to the fore.

It was snowing as I walked to school on that March 15 morning. When I arrived in class, our professor was not yet there. The radio was barking a harsh warning to us to stand by for important news; other students stood around in wondering attitudes. Then the teacher arrived. We turned to him for information and were stunned by his bleak expression; at the same moment the radio announced that the Germans were already in Bohemia and would reach Prague by eleven oclock! Our national anthem was playedfor the last timewhile we stared at each other, not wholly believing. Then our teacher announced that he had orders to dismiss us; he advised us to go directly home.

We joined the shocked, silent people in the street. We drifted with them down to Wenceslas Square in the dense, heavy snow. The square quickly filled with a crowd which stood waiting in silence. Karel Bergmann, Vlasta Chervinka, and I stood together, waiting.

When the motorized infantry came, some people thrust their hands into their pockets and only glared, some made threatening gestures with their fists. Many women were crying.

But nobody shouted. Through the steady-falling snowflakes one could hear only the engines. The cold built up inside of us as well as outside as we watched the invaders roll by.

England wont stand for this! muttered Karel, hardly moving his lips. War will be declared!

Vlasta, white and trembling, nodded. But if England doesnt fightwe must! he said savagely. We must!

Next page