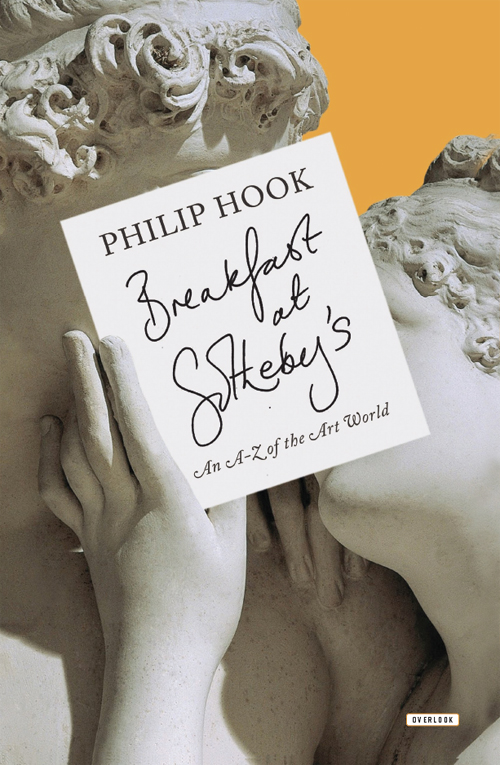

This hardcover edition first published in the United States in 2014 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special orders, please contact , or write us at the above address.

First published in Great Britain by

Penguin Books 2013

Copyright Philip Hook, 2013

All images courtesy of Sothebys other than:

Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2013;

Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013;

The Munch Museum/ The Munch - Ellingsen Group, BONO, Oslo/DACS, London 2013;

Salvador Dali, Fundaci Gala-Salvador Dal, DACS, 2013;

DACS 2013;

The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2013;

The Estate of Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti, Paris and ADAGP, Paris), licensed in the UK by ACS and DACS, London 2013;

DACS 2013;

ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013;

Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013;

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1030-6

When you stand in front of a work of art in a museum or exhibition, the first two questions you ask yourself are normally 1. Do I like it? and 2. Whos it by? When you stand in front of a work of art in an auction room or dealers gallery, you also ask yourself the same two questions first; but they are followed by others, rather less noble-minded, such as: how much is it worth? How much will it be worth in five or ten years time? And, what will people think of me if they see it hanging on my wall?

This dictionary is a guide to how people reach answers to those questions, and how in the process art is given a financial value. I have spent more than thirty-five years working in the art market, first at Christies, then as a dealer, and latterly at Sothebys. That is my excuse for writing a book about the art world that investigates in prurient detail the guilty but ever-fascinating relationship between art and money. It is divided into five parts, each one of which analyses a different factor in what determines the amount a buyer ends up paying for a work of art. In the process I have undertaken a highly subjective and shamelessly self-indulgent tour of those aspects of art and the art world that have struck me over the years as comic, revealing, piquant, splendid or absurd.

The first part examines the artist and his hinterland. Whos it by? The identity of the artist and his perceived importance in the scheme of art history is a factor that has an understandable influence on buyers and the price they pay for a painting; but there is also a back story to artists lives that affects our appreciation of them and the works they produce, a romance made up of the glamour and myth of artistic creation. Quite apart from the art historical importance of say Van Gogh and his significance as the originator of Expressionism, there is a tragic romance to his life that enhances his value to the collector both emotionally and financially.

The second section looks at what subjects and styles are in demand. The answer to the question Do I like it? is influenced by ones own personal predilections, but also by a broader artistic taste that is constantly evolving. At different times in history people want different things from art, so that what artists paint and how they paint it can to succeeding generations vary in desirability and financial value. But within that evolution, certain subjects and styles emerge as selling better than others with a reasonable consistency. This part of the dictionary attempts to analyse the factors in play, and to look at artistic taste as manifested now, in the early years of the twenty-first century. A warning in advance: the determinants of what sells and what doesnt are occasionally subtle ones, but more often alarmingly simplistic.

The third part, Wall-Power, looks in more detail at what makes us like a painting. What gives it the impact that makes us want to own it (and attracts a crowd of other admirers too so that it sells for appreciably more than we can afford)? Of course, surpassing artistic quality is the element always reflected positively in the price a work of art realizes. And, at the very top of the quality tree, the price differential between something that is very good and something that is superlative is astonishinglylarge. That gap is something I find oddly vindicating about the market: in this respect it has its values right. It recognizes the very best and sets it very emphatically apart.

But how does it do it? Artistic quality is notoriously difficult to pin down. Certain contributory factors are examined here: a works colouring, its composition, its finish, its emotional impact, its relationship to nature, and to other works of art. Conversely, on what grounds do we have reservations about a painting that will negatively affect its price? Is it unfinished, or too dark, or heavily restored, or depicting something unpleasant? Could it be, horror of horrors, a fake?

In the same way that an artists back story affects our perception of him and his work, so does the back story of the physical work of art: whose collection it has been in, where its been exhibited, which dealers have handled it. So the fourth part looks at provenance. If the work you are buying comes from a distinguished private collection, it will raise the price because previous ownership by a very eminent collector is an imprimatur of the works quality. A Czanne from the Mellon Collection will be worth more than the same picture from an unnamed private collection. Similarly, to those in the know, certain names appearing in a pictures provenance can trigger alarm signals. These are the dealers that research has identified as having trafficked in looted art during the Second World War, for instance. Unless it can be proved that the painting was not stolen from a Jewish collector, its value may be seriously reduced by its handling by one of these dealers. It may not be saleable at all. And the name of Field Marshal Gring in the list of previous owners of your picture even if he came by it legally isnt necessarily a bonus.

Whats it worth? Art is assessed and changes hands in a constantly evolving market environment. That environment is the product of a vast range of elements: economic, political, cultural, emotional and psychological. It is influenced by the marketing of dealers and auction houses, by the whims of collectors and the caprice of critics, by what people see in museums and on television, by their own individual aspirations. The final section of the dictionary, Market Weather, examines some of the varied factors that contribute to the storms and sunshine of the art-world climate.

Attaching financial value to works of art is not an entirely uncontroversial activity. But on the whole I think the art trade performs a necessary function and does it no worse than a number of other respectable commercial institutions. It has certainly provided me with an interesting life. I have had close encounters with a large number of great works of art (and a large number of less good ones, too, which is also salutary). I have met some extraordinary (and extraordinarily rich) people. This dictionary is an anthology of what I have learned from them. And, having spent two happy decades working for Sothebys, I should of course point out that the conclusions I draw are my own and not necessarily the views of my long-suffering employers.

![Franks - Breakfast greats: [delicious breakfast recipes, the top 90 breakfast recipes]](/uploads/posts/book/201211/thumbs/franks-breakfast-greats-delicious-breakfast.jpg)