ALSO BY EDWARD WILSON-LEE

Shakespeare in Swahililand

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2018 by Edward Wilson-Lee

Originally published in Great Britain in 2018 by Williams Collins

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition March 2019

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Jacket design by David Litman

Jacket artwork: Ship Illustration by Lazy Clouds/Shutterstock;

Old Manuscript by Ariusz Nawrocki/Shutterstock; Old Text by DEA/G. Dagli Orti/Getty Images; Night Sky and Ocean by Jezper/Shutterstock

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

ISBN 978-1-9821-1139-7

ISBN 978-1-9821-1141-0 (ebook)

Endpapers: A page from Hernandos main book register, including (at entry 2091) the entry for the Book of Prophecies that Hernando compiled with his father.

for Kelcey

Achilles shield is therefore the epiphany of Form, of the way in which art manages to construct harmonious representations that establish an order, a hierarchy.... Homer was able to construct (imagine) a closed form because he... knew the world he talked about, he knew its laws, causes and effects, and this is why he was able to give it a form . There is, however, another mode of artistic representation, i.e., when we do not know the boundaries of what we wish to portray, when we do not know how many things we are talking about and presume their number to be, if not infinite, then at least astronomically large.... The infinity of aesthetics is a sensation that follows from the finite and perfect completeness of the thing we admire, while the other form of representation we are talking about suggests infinity almost physically , because in fact it does not end , nor does it conclude in form. We shall call this representative mode the list , or catalogue .

UMBERTO ECO , The Infinity of Lists

Como todos los hombres de la Biblioteca, he viajado en mi juventud; he peregrinado en busca de un libro, acaso del catlogo de catlogos; ahora que mis ojos casi no pueden descifrar lo que escribo, me preparo a morir a unas pocas leguas del hexgono en que nac.

JORGE LUIS BORGES , El Biblioteca de Babel

The use of letters was invented for the sake of remembering things, which are bound by letters lest they slip away into oblivion.

ISIDORE OF SEVILLE , Etymologies I.iii

So if the invention of the Shippe was thought so noble, which carryeth riches, and commodities from place to place, and consociateth the most remote regions in participation of their fruits: how much more are letters to be magnified, which as Shippes, passe through the vast Seas of time, and make ages so distant, to participate of the wisdome, illuminations, and inventions the one of the other?

FRANCIS BACON , Advancement of Learning

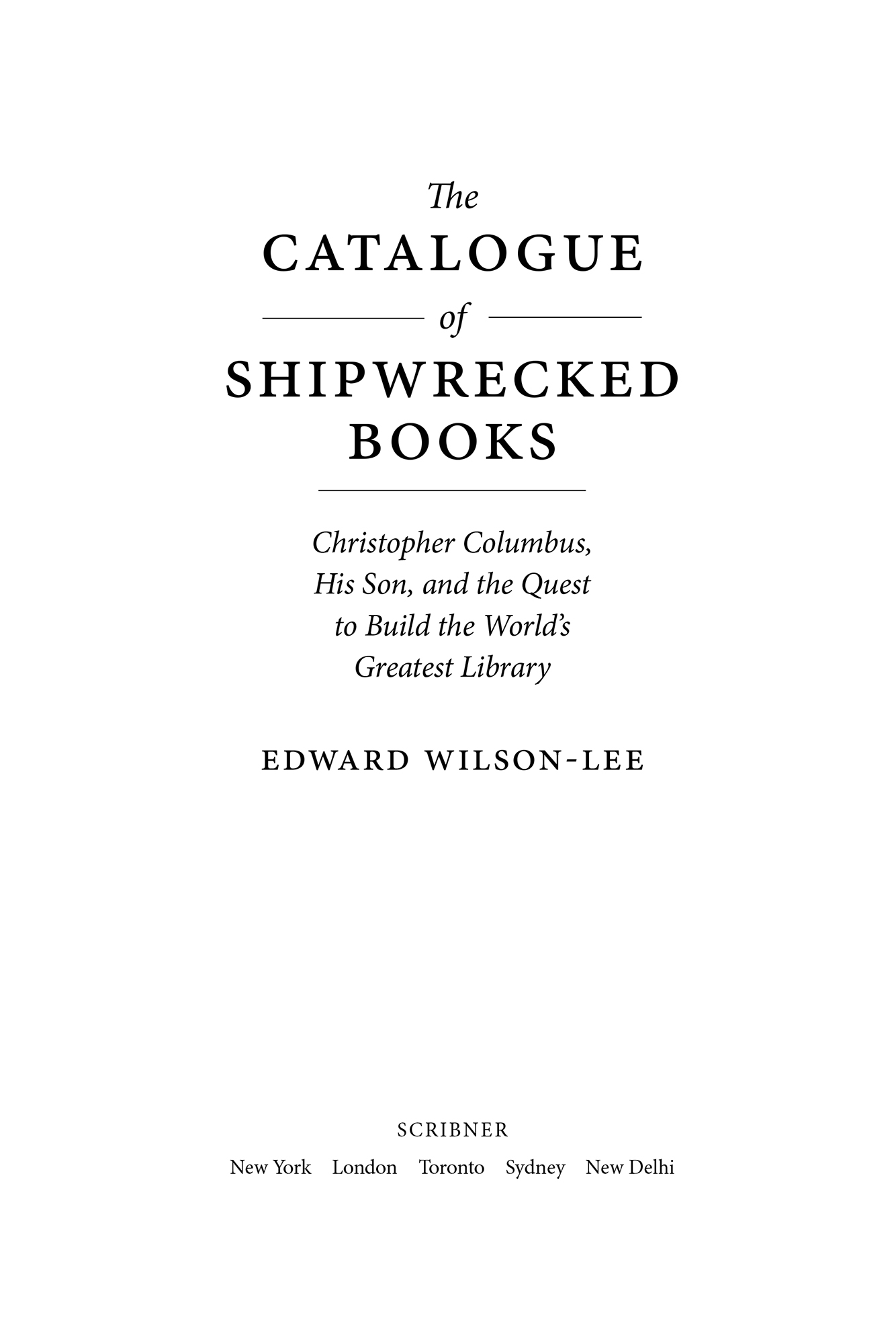

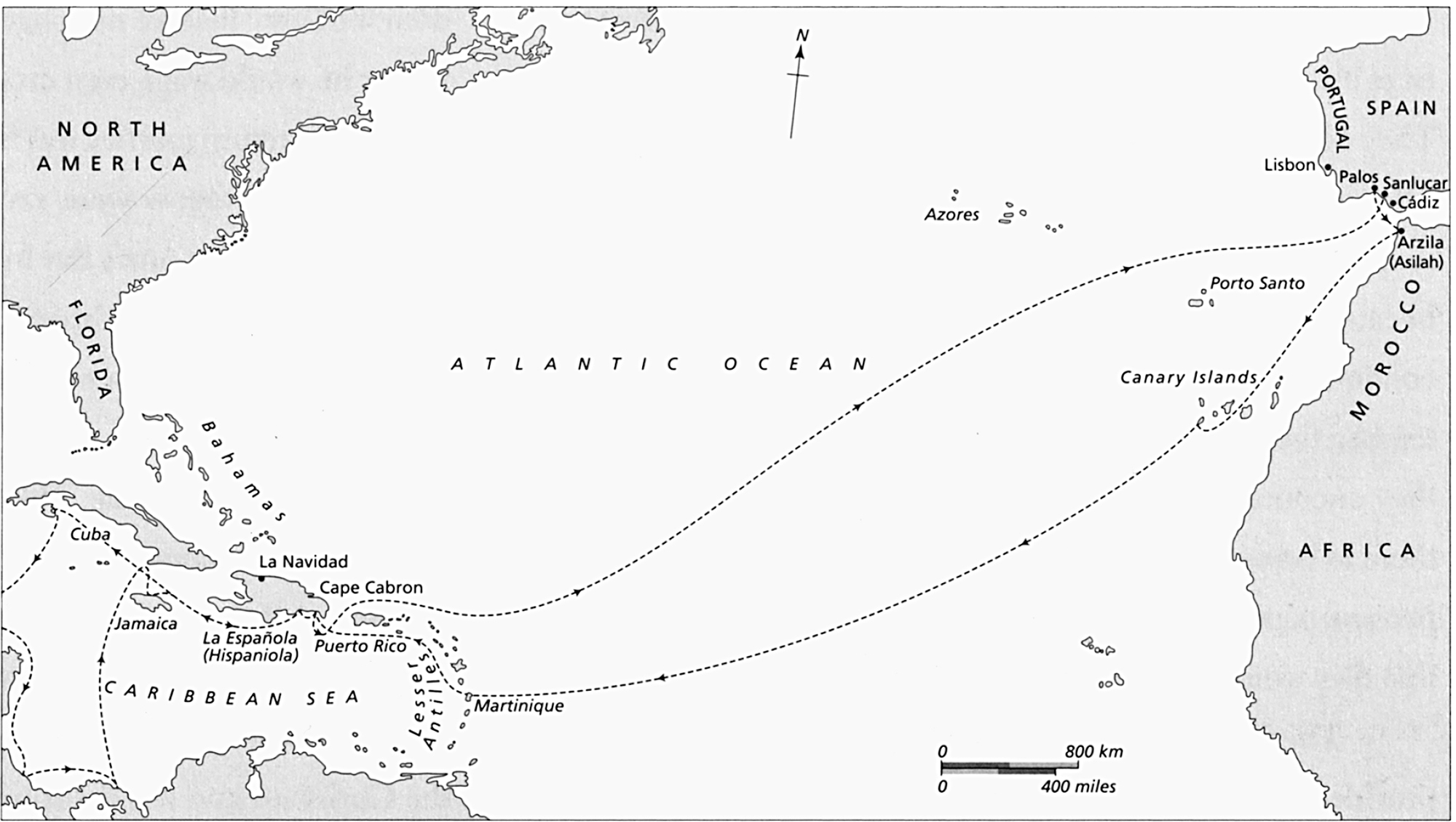

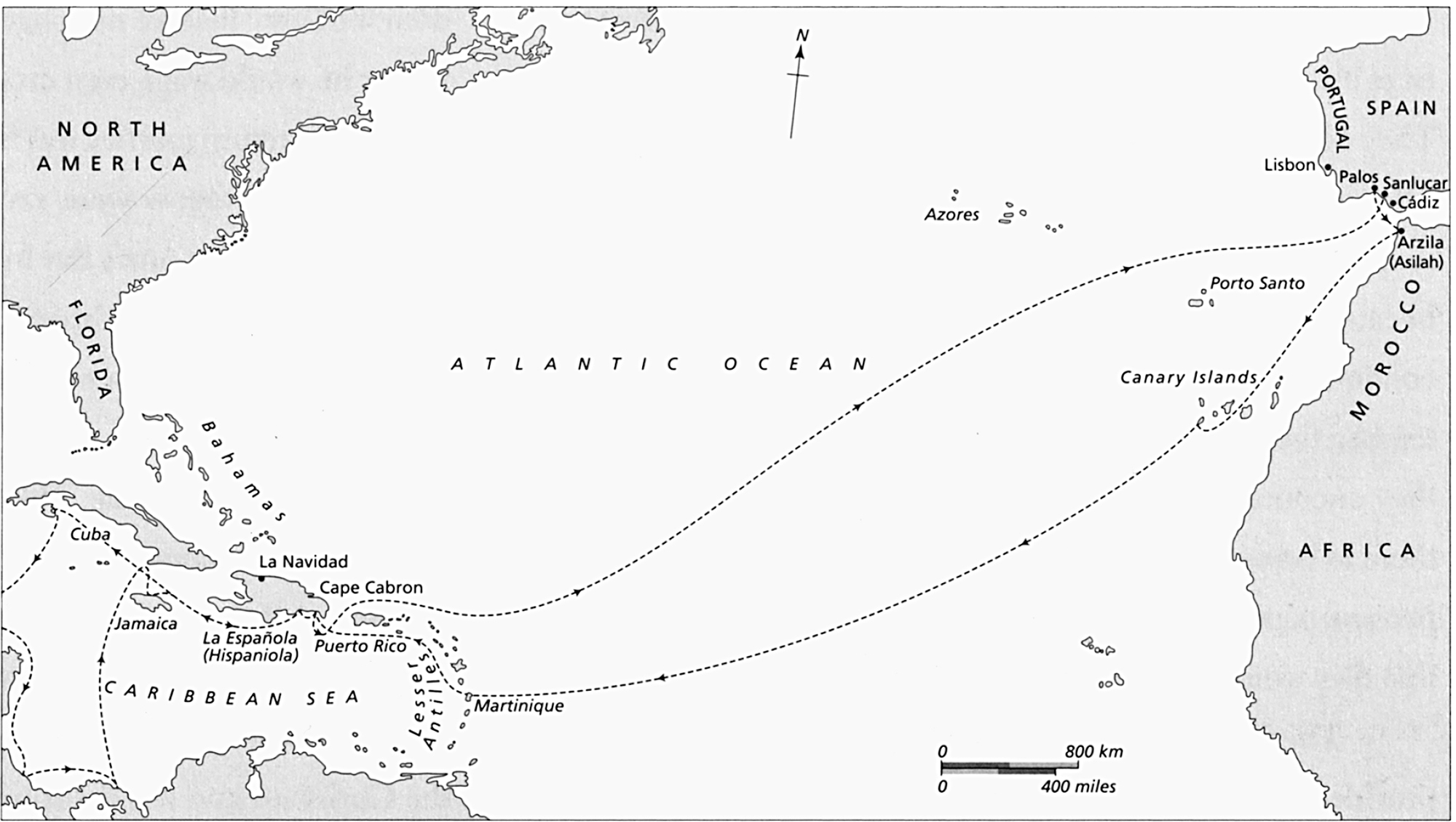

The route of Columbuss Fourth Voyage, 15024, on which he was accompanied by Hernando.

Detail of Hernando and Columbuss route around the Caribbean and Central America in 15024.

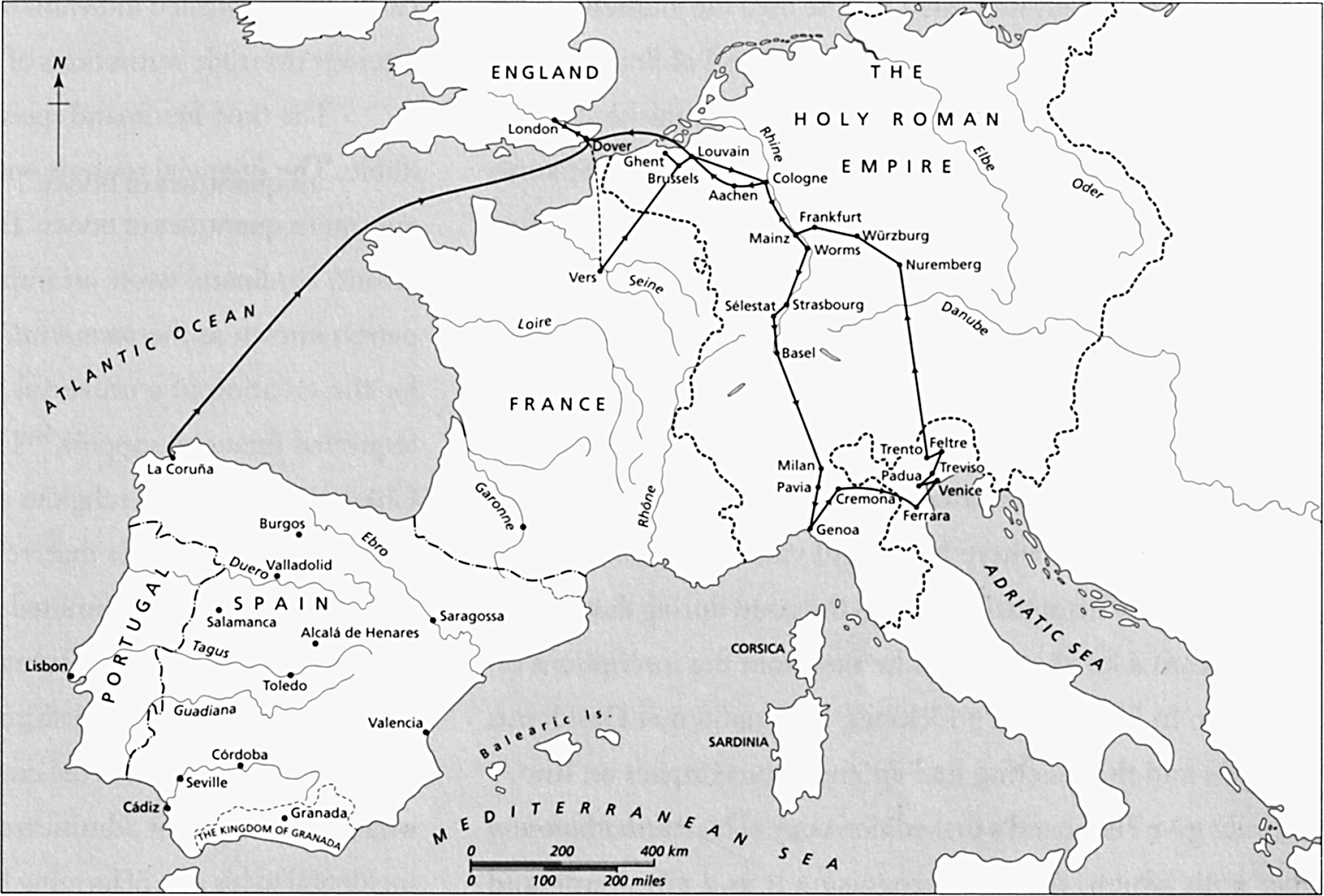

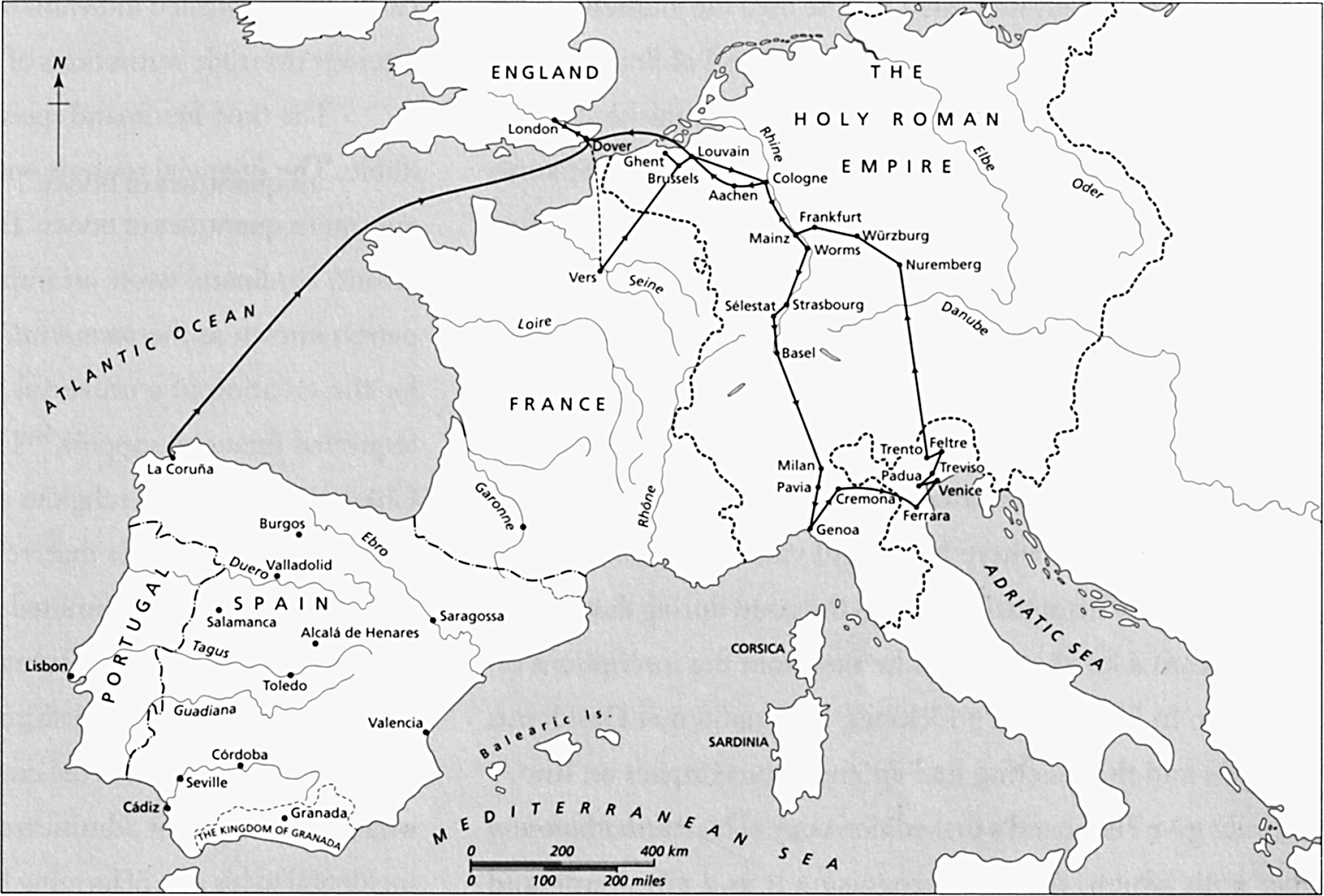

The route of Hernandos journey through Europe in 152022; the dashed portions are conjectured.

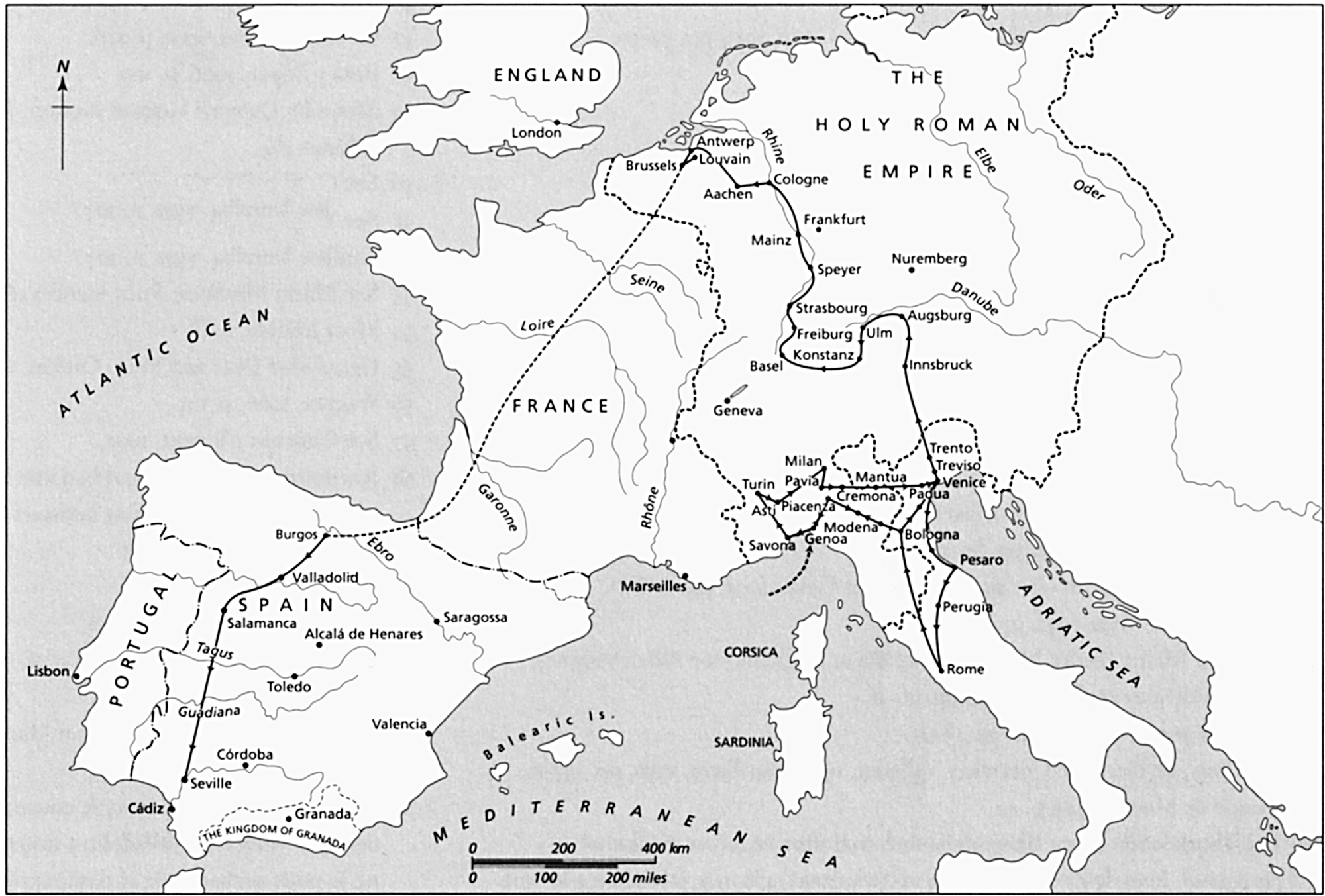

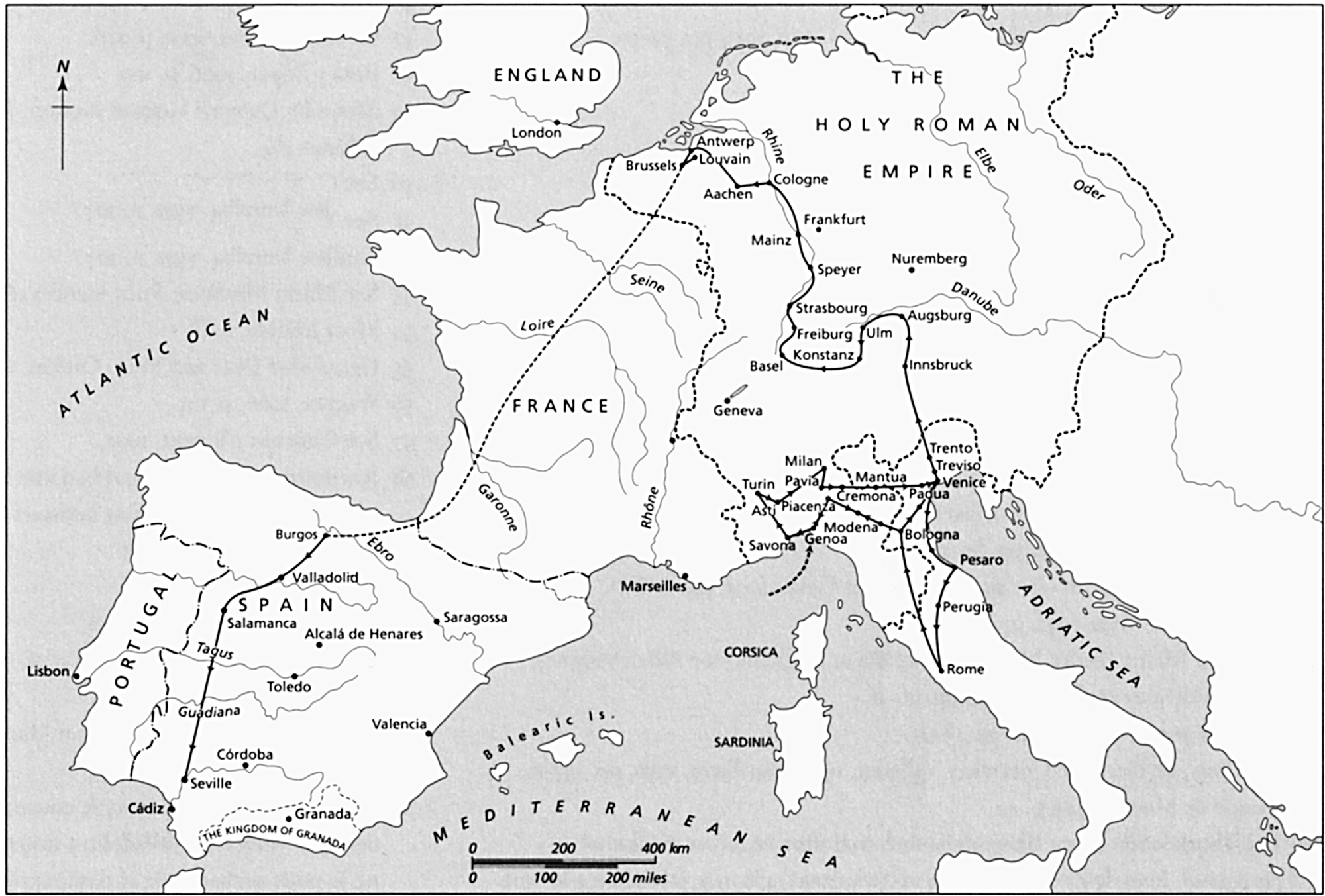

The route of Hernandos journey through Europe in 152931; the dashed portions are conjectured.

PROLOGUE

Seville, 12 July 1539

O n the morning of his death, Hernando Coln called for a bowl of dirt to be brought to him in bed. He told his servants that he was too weak to raise his arms and instructed them to rub the soil on his face. While many of them had been with him for a decade or more and were intensely loyal, they refused on this occasion to obey his orders, thinking he must finally have taken leave of his senses. Hernando mustered the strength he needed and reached into the bowl by himself, smearing his face with the silt of the Guadalquivir, the river that meandered through Seville and held his house in the crook of its arm. As he painted himself with mud, Hernando spoke some words in Latin that began to make sense of this performance for those who had gathered at his side: Remember that you are dust , he said, and unto dust you will return . On the opposite bank of the river, Hernandos fatherChristopher Columbus, Admiral of the Ocean Seahad recently been raised from the same soil, from a grave in which he had lain for thirty years. If Hernandos word is to be believed (and for many things in Columbuss life we have only Hernandos word), the men who opened his tomb may have been surprised to find, along with the explorers bones, a pile of chains. These chains were a link to a moment in Hernandos past, when at twelve years old his mostly absent father appeared bound in them, returning as a prisoner from the paradise he looked upon as his discovery and his gift to Spain.

The meaning of the great explorers grave-goods, of these chains that he wished to be placed with him in his tomb, was something Hernando only divulged late in life, when he came to write his fathers story. But the dust with which he painted himself on the morning of his death would have made sense to all around him: it was a symbol of abject humility, humility he knew he could afford to vaunt because there was no doubt he had achieved something extraordinary. Hernando, the man who was welcoming his impending decay with open arms, had built an engine capable of withstanding forever the onslaught of time. He died shortly after this performance, at eight oclock in the morning.

An hour later the next act in Hernandos strange death pageant began. Those closest to him had gathered at his house for the reading of his will, reaching his Italianate villa by the river by passing through the Puerta de Goles (Hercules Gate) and the garden of unknown plants. Hernando had an extraordinary memory, an obsession with lists, and a delicate conscience, so his will tabulated in minute detail the people to whom he felt he owed something, right down to a mule driver whom he had shortchanged nearly two decades previously. But after the tables of his conscience had been cleared, his testament moved on to its great crescendo, a declaration all but incomprehensible to his time. The main heir to his fortune was not a person at all, but rather his marvelous creation, his library. As this was the first time in living memory that someone in Europe had left their worldly wealth to a group of books, the act itself must have been somewhat confusing; but it was even harder to make sense of given the form of the library in question. Most of Hernandos books were not like the precious manuscripts treasured by the great libraries of the dayvenerated tomes of theology, philosophy, and law, books that were often sumptuously bound to reflect the great value placed upon them. Instead, much of Hernandos collection consisted of books by authors of no fame or reputation, flimsy pamphlets, ballads printed on a single page and designed for pasting on tavern walls, and other such things that would have seemed just so much trash to many of his contemporaries. To some eyes, the great explorers son had left a legacy of