Discovery at Rosetta

Discovery

at

Rosetta

Jonathan Downs

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

This electronic edition published in 2020 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

One Rockefeller Plaza, New York, NY 10020

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2020 by Jonathan Downs

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 9267

eISBN 978 161 797 9699

Version 1

For my father

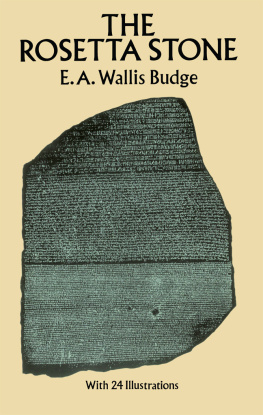

This second edition, published by the American University in Cairo Press, includes a new appendix an overview of the medieval Arabic scholars who attempted to decipher hieroglyphics. Too often it is forgotten that the Rosetta Stone is an Egyptian and not European artefact, its roots deriving from a region that has undergone dramatic cultural change over the centuries since Rome the most extensive of which is arguably the advent of Islam.

The Golden Age of Islam, in the early Middle Ages, brought with it a burst of scientific curiosity and experiment similar to that of Europes Enlightenment. Islamic scholars of the day by no means ignored the all too evident remnants of ancient Egypt, as has been largely supposed by many European historians. For some time, I have wanted to acknowledge the many medieval Arabic scholars who gained ground in the translation of hieroglyphics, but whose efforts are rarely mentioned in popular English-language commentaries of the great nineteenth-century decipherment.

One of the reasons for writing the original book was to dispel myths, clarify a confused chronology and add the names of soldiers, sailors and scholars forgotten by popular histories hence the inclusion of the first English translation of the Memphis Decree, by Stephen Weston, and the work done by the Philomathean Society of Pennsylvania. Perhaps now, in the second edition, with the inclusion of such thinkers as Dhu al-Nun and Ibn Wahshiyah, the appendices are more complete. There has been some contention regarding the impact of their work on Champollions efforts, as there was once about Youngs, but this is not surprising: as it was in the nineteenth century, any investigation or criticism of Champollions efforts is often interpreted as nationalist or culturalist bias; and, given our sensitive global situation, any research into the Arabic scholars can be seen as religiously or politically motivated equally, its dismissal also an example of cultural prejudice. I would leave it to specialists to draw their own conclusions, but hope these additions will point researchers in the right direction for further investigation.

Since writing the first edition, Egypt underwent tumultuous revolution during the Arab Spring of 2011. There could be no greater indication of the dedication of the Egyptian people to their cultural heritage than their selfless defence of archaeological sites across Egypt, including the Alexandria Library (the Bibliotheca Alexandrina), Cairo Museum and French Institut dgypte, even in the face of riot and armed violence. Their actions, I hope, will serve as reminders of popular feeling as the repatriation debate continues. The two-hundredth anniversary of Champollions decipherment of hieroglyphics and the Rosetta Stone provides an ideal opportunity to revisit the argument, and perhaps find a solution acceptable to all.

I would like to thank a number of people for their considerable assistance with the research of the first and second editions of this book: Dr. Patricia Usick, honorary archivist, and Dr. Richard Parkinson, keeper of the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan at the British Museum; Adrian James, chief librarian at the Society of Antiquaries of London; Dr. Frances Willmoth at the library of Jesus College, Cambridge; Dr. Brian Muhs at the University of Leiden; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and the Philomathean Society of the University of Pennsylvania.

From France, I would like to thank Yves Laissus, Roland Pintat of the Bibliothque nationale, and Marie-Claire Cuvillier, Secrtaire gnrale of the Socit franaise dgyptologie, who provided generous support, research and access to the work of the esteemed Jean Leclant. Thanks also to former editor Peter Furtado, Charlotte Crow and Sheila Corr of History Today magazine in 20062008, and current editor Paul Lay; Rob Gray, House and Collections Manager of the National Trust property Kingston Lacy; Middle-East specialist Dr Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani; historian John Norris; Trudy Foster of the Jersey Heritage Trust; L/Sgt Gorman of the Scots Guards archives; authors Paul Strathern, Dorothy King, William St. Clair; Dr David Dalby; and The Egyptian Society of South Africa for their interest and support.

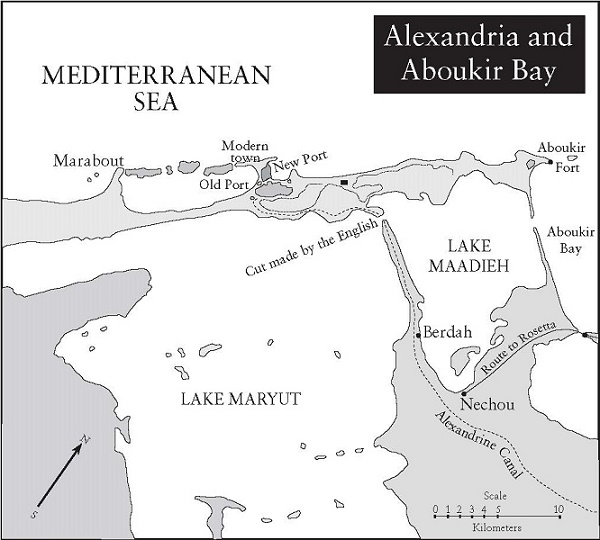

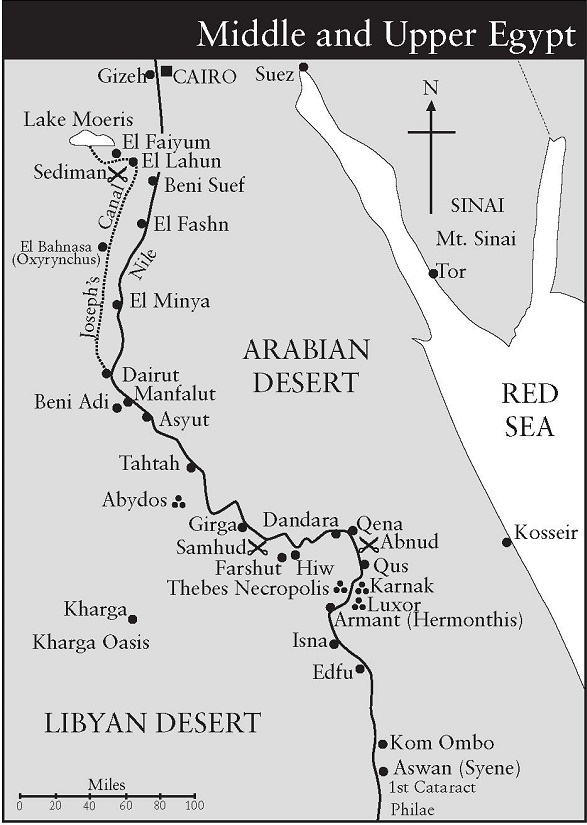

From an original map by savant douard de Villiers du Terrage, showing the cuts through the Alexandrine Canal, which flooded the once dried-up plain of Lake Maryut with the waters of Lake Maadieh, isolating French Alexandria during the Anglo-Turkish siege of 1801.

The Sword and the Stone

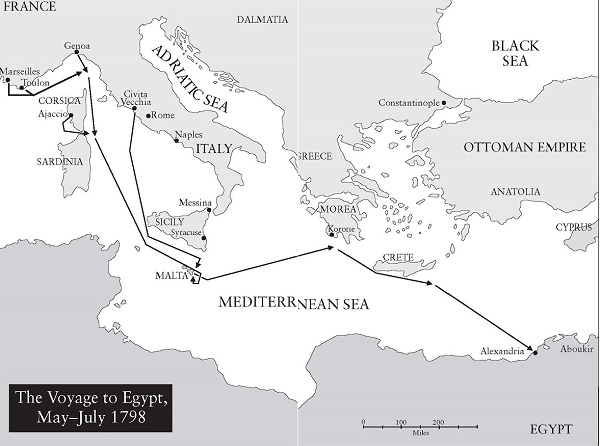

Somewhere out to sea, bearing down furiously upon the sweltering coast of Egypt, came an invasion fleet sent by the greatest power in the East. Crammed aboard the plunging decks, clutching musket, pistol and razor-sharp yataghan sword, were 15,000 Ottoman Turks bent on revenge: after Bonapartes slaughter of their countrymen in Palestine and his desecration of the Holy Land, they were coming for French blood.

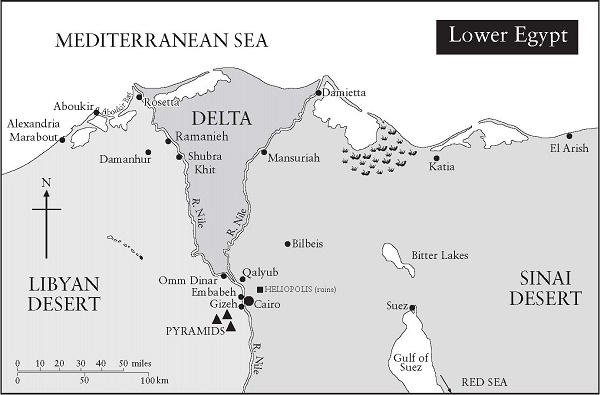

The attack due at any moment, chef de brigade Dhautpoul, battalion commander of the engineers in the Delta, ordered Lieutenant Pierre Franois Xavier Bouchard to repair and reinforce the crumbling outer wall of Fort Julien, on the shores of the west branch of the Nile. The ancient stone castle stood just to the north of a small, palm-lined port called Al-Rashid known to Europeans as Rosetta. As others anxiously scanned the horizon for signs of Turkish sail, Bouchard hurriedly organized his platoon and labourers. Little did he realize, in the midst of their frantic efforts, that he was about to make an extraordinary discovery a discovery that would open the floodgates of history, reviving the gods of the Nile after two thousand years of their patient, megalithic meditation. Bouchards engineers would unwittingly provide the key to the greatest mystery of this most ancient of antique lands.