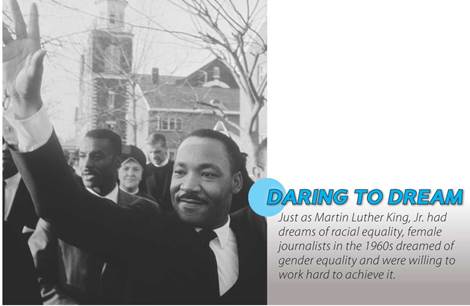

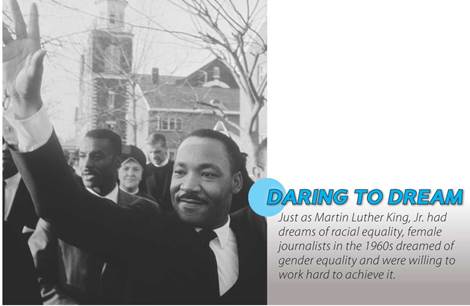

Imagine being a reporter during MartinLuther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Or interviewing the firstwoman in America to vote. Or reporting from Vietnam with the war raging allaround you. Marlene Sanders did all of this and more and she wasone of the first women to do it.

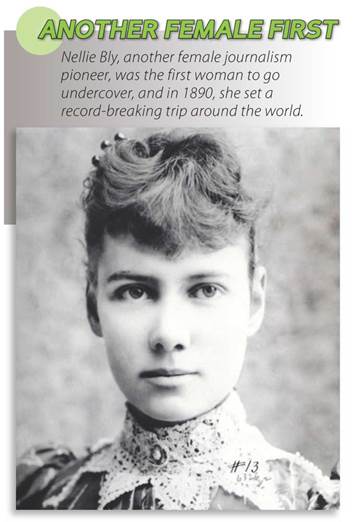

Women have been a part of the journalismworld since the 1800s.

However, for many years they were keptfrom working as professional journalists because of their gender. While afew women, such as Marlene Sanders, found their way to a professional c areer, the majority of women worked as secretaries andresearch assistants. The women who were hired as journalists weren't allowed towrite. They would do the research for a story, then give it to their malecounterparts to write. In the early days of jou rnalism,these women were jokingly called "dollies" by their bosses. They wereviewed as the pretty faces at the workplace, not as actual contributing membersof the team. They were told that there would never be a real place for them inthe world of media .

However, when the women's movementgained power in the 1960s, so did the dollies. The women working for Newsweek were the firstto take a stand. With the help of one of the only female lawyers in practice, the 46women employees of Newsweek were the firs t group of mediaprofessionals to sue their company for unfair treatment based on gender. Whenthe Newsweek women took their story to the public on March 16, 1970, itquickly gained national attention and support. Only two days after their storywent publi c, the ladies who worked at Ladies' Home Journal staged their own sit-in, and other groups quickly followed.Women in journalism refused to work until they were treated equally. Thanks tothe work of the dollies, women were able to move up in the world of journalism. The few women who were already working asjournalists, such as Marlene Sanders, were now able to move even higher, pavingthe way for others.

Marlene Sanders knew from an early agethat she wanted to be in front of cameras. So, after a year of college, Sanders moved to New York to pursue a career inacting.

However, the theater was harder to breakinto than she anticipated. It wasn't working out as planned; so, in 1955 whenMik e Wallace offered her a job at WNEW-TV, Sanderstook it. As it turned out, it was the perfect fit.

At WNEW-TV, Sanders worked in a smallunit, and was therefore expected to carry her weight. Unlike the dollies whowere stuck pouring coffee, Sanders was lea rning howto dig for facts, edit, write, and produce. Sanders was a hard worker, andquickly moved up the WNEW-TV ranks. Mike Wallace saw her potential, and refusedto let her gender keep her from being an asset to the company.

By 1962, Sanders was the assistantdirector of news by far the highest position reached by any woman in thefield. But Sanders pushed even higher.

In 1964, Sanders went to work as a NewYork correspondent for ABC Ne ws. At ABC, she got herbiggest breakshe became the first woman to anchor a nightlynewscast for a major network. Sanders paved the way for women in journalism byproving that gender didn't matter. However, she wasn't alone in her fight. Manywomen, such as Jeannie Morris, were fighting to maketheir voices heard in the world of black and white.

Spor tsreporters in the 1960s were not hard to identify: former professional athleteswith good hair, big smiles, and a complete understanding of the game. So, whenJeannie Morris, the 5'2" wife of NFL wide receiver Johnny Morris, decidedto join the world of sports reporting, everyonethought she was crazy; she definitely did not fit the profile.

Jeannie got her big break thanks to thehelp of her husband, Johnny. When he retired from the NFL, the Chicago American asked Johnny if he could write anewspaper col umn about football. He told them,"I can't. But my wife can."

Though they were skeptical, the Chicago American gave Jeannie her own column, called "Football is aWoman's Game" by Mrs. John ny Morris. Though thecolumn still possessed her husband's name, people quickly fell in love withfootball through the eyes of Jeannie.

In fact, Chicago loved Jeannie so muchthat she was offered a job at the Chicago DailyNews as a sports reporter. Well, sort of. Although Jeannie was a sports reporter, she wasnever a "beat reporter," who reported the scores and statistics ofthe game. As a female, she wasn't allowed in the locker rooms and even in somepress boxes so she couldn't talk directly to the play ers.Instead, Jeannie wrote interest pieces about the players, and gained popularityfor herself, and the sport, by making the athletes come to life.

Jeannie then moved on to television,where she worked with some of the biggest stations in the nation, inc luding CBS.

At CBS, Jeannie took many large stepstowards women's equality. She was the first woman to interview players in thelocker room, and in 1975, the first woman assigned to report live from theSuper Bowl. However, when she showed up at the Super Bowl, she wa s told she was not allowed in the press box because she wasa woman. But that didn't stop her. Instead, she did her report sitting on thetop of the press boxin the middle of a blizzard!