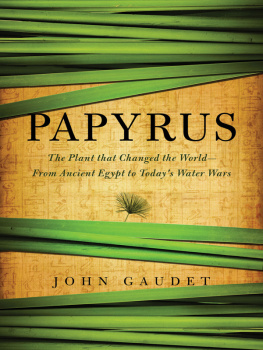

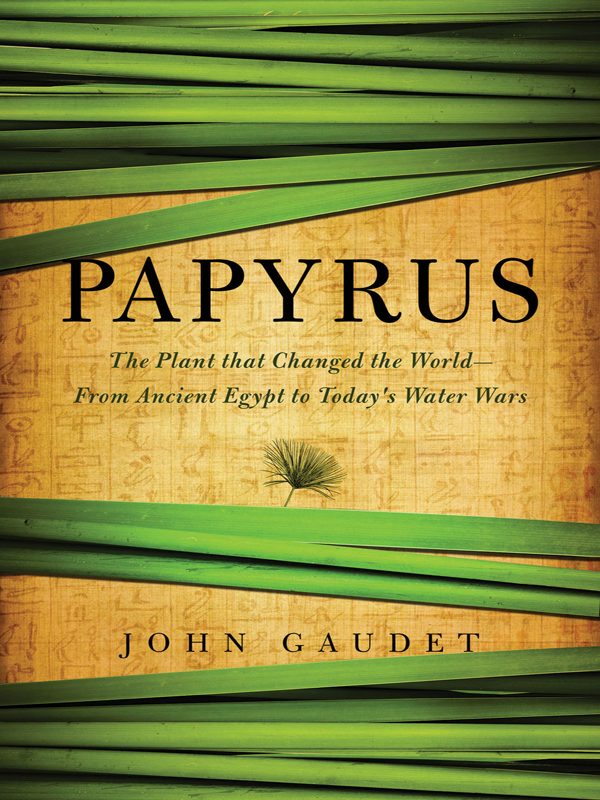

PAPYRUS

The Plant that Changed the World

From Ancient Egypt to Todays Water Wars

JOHN GAUDET

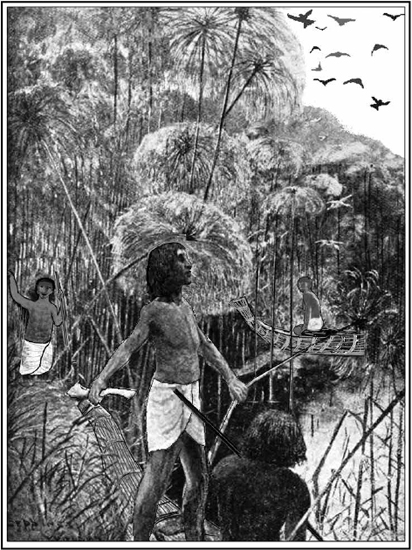

Stone Age marsh men hunting in an ancient papyrus swamp in the Nile Valley, 5000 B.C.

PAPYRUS

Pegasus Books LLC

80 Broad Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10004

Copyright 2014 by John Gaudet

First Pegasus Books cloth edition June 2014

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-60598-566-4

ISBN 978-1-60598-597-8 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

To the millions of young people who will lead the way to the new world, a place where I hope swamps and marshes will flourish and peace and harmony will prevail.

MAPS

Map 1: Nile catchment, Sudd area, and Lake Victoria. p. 17

Map 2: Rain-fed savanna of archaic Egypt and the water-world. p. 21

Map 3: Major papyrus paper centers in ancient Egypt. p. 25

Map 4: The Jordan River, Huleh Valley, Huleh Swamp, and Lake Amik. p. 126

Map 5: The Congo River catchment, central wetlands, and sites of the Grand Inga Dam and Transaqua Canal. p. 141

Map 6: Lake Naivasha 50 years ago. p. 192

Map 7: The general reduction of Lake Naivasha and change in wetlands and the towns. Since 2009, the water level has come back up but the wetlands are gone. p. 194

Map 8: Major swamps of the Zambezi region. p. 213

Map 9: The Okavango Delta (based on NASA, FAO Aquastat 2005, and OKACOM). p. 231

Map 10: Jordan River, the Huleh Swamp, Lake Agmon, the new Reserve on the Jordan, and the Peace Park on the Yarmouk River. p. 242

Map 11: Bird migration routes passing through the Huleh Valley (courtesy Y. Leshem). p. 247

PAPYRUS

Where the Eastern waves strike the shore... or where the seven-mouthed Nile colors the waters, ... whatever the will of the heavens brings, ready now for anything...

Catullus, 6154 B.C.

A resource treasured by the kings of Egypt, a prince among plants, a giant among sedges, and a gift of the Gods, the papyrus plant has been with us since the dawn of civilization. It allowed Egypt to be papermaker to the world for thousands of years and in doing so ruled the world in the same fashion that King Cotton ruled the South, the demand being met exclusively by the papyrus swamps of Egypt where it grew at a phenomenal rate.

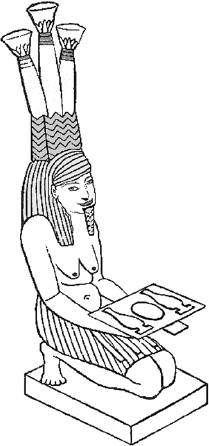

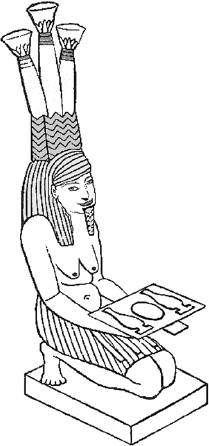

Where did papyrus come from? To an early Egyptian this question was so obvious he need not say a word; he could simply point to a relief or a statue of Hapi, the god of the Nile inundation. This shows a seated, blue-colored, chubby man with pendulous breasts, a Pharaohs fake beard, and a belly hanging over his girdle. Bizarre, yes, but in a way not entirely foreign to some of us who are entranced by that most impressive Hindu god, Krishna, who was blue-skinned, said to be the maximum color in nature as in blue skies, oceans, lakes, and rivers, thus an appropriate color for special people.

Hapi, the god of the inundation (after Budge).

What I really find striking about him is his crown, which looks like a large clump of papyrus growing from his head.

The popular notion was that the plant was a sacred gift, much like the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden. In reality, papyrus came to us, as did many flowering plants, after a long stage of evolution from primeval Jurassic ancestors. It had already been established in the Nile Valley and elsewhere in Africa for thousands of years before the early settlers arrived. The important thing was that these settlers (see frontispiece) recognized papyrus as a good thing and fell in love the minute they saw it. They had come to the Valley because of the river, and they stayed on because they wanted no more to do with the Sahelian droughts of 60005000 B.C.

In the Nile River Valley they found a permanent sustainable existence, a part of which was the swampy terrain, a water world made up of quiet pockets of water and patches of waterlogged soil scattered throughout Egypt. And there, growing in the flooded areas, was Egypts new partner, papyrus, a viable hunting preserve, a source of reed for boats, housing, rope, and crafts, and above all an eye-catching part of the landscape.

After having evolved over millions of years, papyrus could be counted on to produce a swamp community that was in equilibrium with itself and a species that was perhaps more extensive, more useful, more efficient, and more luxuriant than anything seen today, because at that time the air, soil, and water quality were almost untouched, unspoiled. Thousands of years in the future, the ancient Egyptian would disappear and the eternal marriage would be dissolved against all reason, and afterwards, like some brave widow, papyrus would carry on, serving different masters through the yearsPersians, Macedonians, Greeks, Romans, and finally Arabs, all of whom would use her in turn. Yet despite everything, she stayed green, lush, fragrant, and self-contained until the very end.

As Herodotus once famously noted, Egypt is a gift of the Nile, and so also were the swamps and marshes that formed in the backwaters of the early river, swamps which served as a natural larder with fish thriving in swamp pools year round and birdlife for the taking. These swamps developed in the floodplains (or upper Nile), then as soon as the river deposits changed from sand to silt they spread downstream into the delta (or lower Nile).

That change in the delta coincided with the migration of people from the Sinai who, like those of the Sahara, were also escaping droughts.

The water of the main river and floodplain averaged about 2 miles in width and was hundreds of miles in length (570 miles from Thebes to the sea) and provided a mighty internal highway to allow the development of Egyptian civilization. This could not have been possible, according to Fekri Hassan, Petrie Professor of Archaeology at the University College, London, without riverine navigation, which requires a boat. Yet forest trees and wood being in short supply, and carpentry skills lacking, they turned to papyrus. As Steve Vinson, an expert on Egyptian boats, pointed out: It is difficult to believe that there was ever a time when humans failed to take advantage of the ubiquitous papyrus to build rafts or floats. Thus evolved, in those early days from 6000 B.C. onward, the reed boat, which must have been a godsend to a hunter-fisher-gatherer.

The Egyptian wasnt alone in this discovery. In those days, throughout several river deltas in the arid world, and the lake cultures in treeless high altitudes, reeds were used to build boats, houses, and everything that made life easier while the early families established themselves in these regions.

Next page