Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

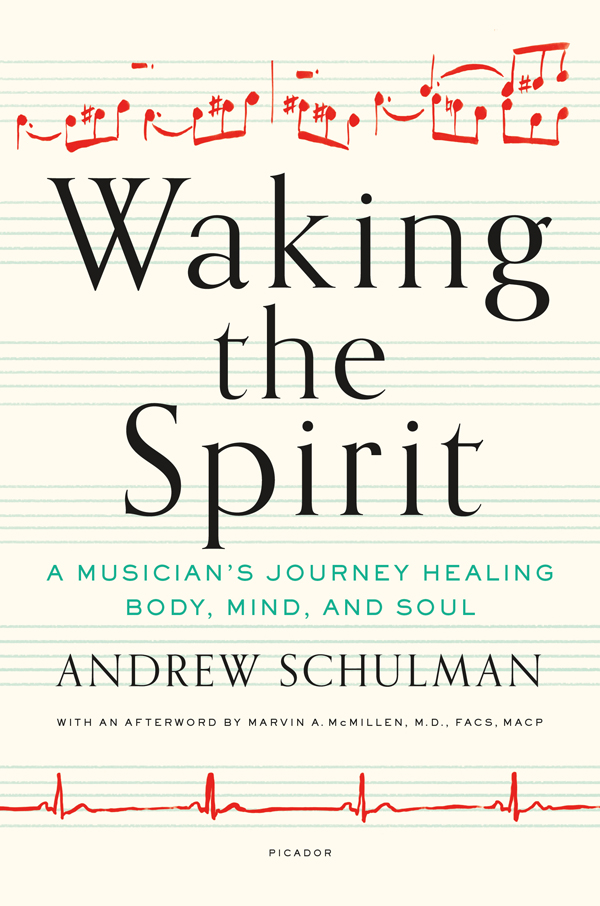

To Peter J. Horoszko (19882016)

PJ, whose spirit will always be at the very heart of this book

This is a true story, though some names and details have been changed. No patient referred to in this book has been named or identified without their express written consent.

To the extent that the information contained in this book discusses or involves medical treatments of any kind, it is not intended to replace the advice of the readers own physician or other medical professionals. In making their own health care decisions, individual readersor their caretakersare solely responsible for the results of those decisions, and the author and publisher do not accept responsibility for any adverse effects claimed to result from those decisions.

Medicina sanat animam per corpus, musica autem corpus per animam.

(Medicine heals the mind, soul, and spirit by the body, but music heals the body by the mind, soul, and spirit.)

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Conclusiones Nongentae, 1486

I turned the corner into the Surgical Intensive Care Unit and a wave of sound hit me. It always did. Beeps from ventilator machines, infusion pumps, and cardiac monitors. The cacophony of voices of doctors, nurses, patients, and visitors at every volume and intensity. And the ever-present discordance of televisions turned up way too high. It struck me again that this was the worst environment for the critically ill to heal. Today there was another noise, a sound I had never heard before, and I stopped in my tracks, unsure. Strange words, very fast and loud, neither happy nor angry, streamed from a bed at the far end of the hall. A womans voice talking. But I couldnt understand a word she was saying or even make out the language she was speaking. It was just a barrage of sound. I had no idea what was going on.

The voice flowed out from behind the curtain of Bed 5, taking over the whole ward. I saw nurse Richard Spatafora bolt out and dash to the Nurses Station, his face anxious. We need the music therapy tapes. Something. Quickly.

Its okay, said a nurse. Andrews here.

Richard whipped his head toward me. Thank God, he said. Andrew, get your guitar ready as fast as you can. We need you. I nodded, pulling my guitar from its case and grabbing my blue music folder marked BACH . I followed Richard behind the curtain, not sure what to expect.

The patient, a woman I guessed to be in her sixties or seventies, sat up in bed with a gauze bandage wrapped around her head. Probably from brain surgery. She looked past me, brilliant blue eyes sparkling, her smile radiant, talking, talking in this loud, melodious tongue. It sounded like Russian. She looked Russian with her high cheekbones. She was beautiful.

There were two other nurses in this small space with Richard, and they all jangled with nerves. Exhausted. Richard shook his head and looked at me. Shes been like this for two hours now. His voice was flat. Shes tied us all up. We cant get her to settle, cant get to the other patients.

I pulled a chair up to the end of the bed, set up my music stand, and for a few moments just looked and listened. The patient was talking still, her monologue seeming never to run dry. What could she be saying? She laughed, looking around, shifting constantly in the bed, fighting to get out. I noticed her arms were restrained, tied to the side rails with white plastic strips. But she didnt seem scared or anxious. I realized she wasnt actually talking to the nurses, but seemed to be conversing with people nearby that only she could see. She smiled the whole time, her words pleading but never angry. It was hard to watch but I couldnt look away. She was so lost, as if she were stuck in another place where we just couldnt reach her.

I settled in, took a deep breath, and started to play my guitar arrangement of the Prelude from Bachs First Cello Suite . At the sound of the first note she turned her head toward me, looking at my face and then at my right hand as it plucked the strings of the guitar. Gone was the scattered expression from her face as her eyes gained focus. She stopped talking, her mouth half-open in surprise, silent. Her face and shoulders relaxed, and she smiled. Not the plastered grin of before but a real smile of pleasure. She was here now, in this room, and not wherever shed been for the past few hours. Something was connecting. We were just ten seconds into the music.

Richard let out a sigh of relief, smiled, and gave me a thumbs-up. I grinned, wide. One by one, Richard and the other nurses left, slipping through the curtain, able to tend to other patients. It was just me and the patient now. The Russian woman.

I played one piece after another for her without a break. She was calm, settled in the bed. Listening. As I brought a chorale melody to an end I paused, thinking about the next piece to play. Immediately, she started to struggle, pulling at her restraints as if she wanted to clamber out of bed. I moved swiftly into a lively Bach minueta type of dance. As the music started up, she calmed again. I noticed if I moved my body, swaying to the rhythm of the music, it engaged her attention even more. I decided to spend my whole ninety minutes at her bedside.

She talked to me as I played. I still had no idea what she was saying, but it wasnt the senseless sounds of before. She was communicating with me now. Reaching out, as my music reached out to her. Thirty minutes went by, then an hour, her attention never flagging as long as I was playing. A doctor on rounds stopped by for a minute to check on her. She leaned back when she saw him, looked up, and in a small, childlike voice said, Beautiful sounds. I was surprised and delighted. She had found her own voice again.

It was almost time for me to leave. Id been playing short, melodic pieces, and they were working well, keeping the patient calm, but I wanted to go a step further. To play one of Bachs most profound fugues, one of the most intricate forms of music ever devised. I decided on the fugue from the Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro written late in his life. As I started to play the deceptively simple opening melody, she gazed at me, grateful, and settled back into the pillows of her bed. Completely at peace. She closed her eyes, and I played just for her. Somewhere at the edges of my mind I remembered that we were in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) and that machines hummed and beeped all around us, but then it was just the music, the patient, and me. For seven minutes I watched her face. The fugue had worked. The word fugue comes from the Latin fuga, which means flight or fleeing. And the patient had done that. She slept peacefully now, far from this jarring environment, partially healed by music. At the end of the fugue, I packed my guitar and my trusty pages of Bach and slipped away.

* * *

I left the SICU that day deep in thought, profoundly affected by the patient in Bed 5. I still thought of her as the Russian woman, although Id found out from a nurse that she was American, from a small town in upstate New York. The language shed been speaking at first was gibberish, although a very fluent form of it. Id learned she had undergone brain surgery the day before and sometimes, after that kind of operation, the nerve synapses misfire for a while and bring on bizarre behaviors. Several things really struck some chords with me. The inability of the nurses, and I knew how great these nurses are, to get through to the patient to help her. The failure of all the modern medicine around her to heal her. The amazing and rapid change that music effected on her, by reaching some deep place in her brain. And the fact that Bach was the agent of that change. I rushed home to my computer, determined to find out everything I could about the power of music to heal. Another leg of my journey had just begun.