Copyright 1996, 2014 by Peter G. Tsouras

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by David Sankey

Cover image: Storming the Teocali by Emanuel Leutze, 1848

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-459-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-179-9

Printed in China

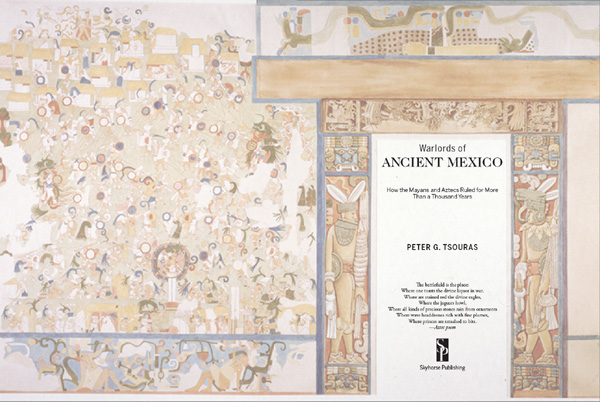

Overleaf: Part of the mural on the west wall of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars, Chichn Itz; watercolour copy by Adela C. Breton

Dedication

When Odysseus wanted to commune with the spirits of the dead, he poured a blood offering into a pit to summon their shades from Hades. That was myth. Scott and Stuart Gentling have surpassed him in reality. As their brushes touched canvas, a magical vision breathed life back into a vanished civilisation of a mighty and terrible splendour. Nezahualcoyotl, the Poet King of Texcoco, rightly described such art as a tribute of beauty, and a long-dead Nhuatl poet unknowingly spoke of them in this poem:

The artist: a Toltec, disciple, resourceful, diverse, restless.

The true artist, capable, well trained, expert; he converses with his heart, finds things with his mind.

The true artist draws from his heart; he works with delight;

does things calmly, with feeling; works like a Toltec;

invents things, works skilfully, creates; he arranges things; adorns them; reconciles them.

This book is happily dedicated to Scott and Stuart Gentling, the Toltec brothers from Fort Worth, Texas.

Acknowledgements

For excerpts from published material, I wish to gratefully acknowledge the following:

Bernal Diaz del Castillo, The Discovery and Conquest of New Spain, published in 1956 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Nigel Davies, The Aztecs: A History, copyright 1973 by Nigel Davies. First published in 1973 by Macmillan, London Ltd. First published 1980 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Publishing Division of the University, Norman.

Fray Diego Duran, The Aztecs: The History of the Indies of New Spain, translated by Doris Heyden, translation copyright 1964 by the Orion Press, Inc., renewed 1992 by Viking Penguin; used by permission of Viking Penguin, division of Penguin Books, USA Inc.

Frances Gillmor, The Flute of the Smoking Mirror: Nezahualcoyotl Poet King of the Aztecs, published in 1965 by the University of Arizona Press.

Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, The Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 12: The Conquest of Mexico, published in 1979 by the University of Utah Press and the School of American Research.

Contents

Preface

The history of the Old World resounds with the deeds of men of warconquerors and warlords, the founders and breakers of empires. The history of the original inhabitants of the New World, especially Mesoamerica, does notbut not for the lack of such men. These histories in English consistently emphasise either the culture and history in general or the Spanish Conquest. Native Americans, under the tramp of whose feet worlds trembled, are submerged in the broader histories or are secondary characters in the story of the Spanish Conquest. Biographies are almost nonexistent, except, of course, that of Corts, and the two splendid histories of Nezahualcoy-otl and Motecuhzoma I by Frances Gillmor in the early 1960s. Almost nothing has been written in which these Native American conquerors and warlords are centre stage.

Warlords of Ancient Mexico is a history of these men. The story stretches from Tikal of 378 AD to the death of the last Mexica emperor in 1525. In the 1147 intervening years, war scoured as bloody a course as it did anywhere else on this planet. And as elsewhere, civilisation was pushed along new paths, both destructive and creative. These men were the agents of great change and compelling individuals in their own rights. The reader of Mesoamerican history is constantly reminded of parallels with their counterparts of the Old World. In the histories of which we are familiar, the year 378 AD is recognised for the defeat of the Roman Army and the death of the Roman Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople, a pivot of history. History also pivoted in that same year as the warlord of Tikal in Guatemala employed the techniques and cult of the new Venus-Tlaloc warfare now called Star Wars, to conquer the neighbouring kingdom of Uaxactn and kill its king. He set a fire in the Maya lands that would burn for four hundred years and then travel north to scorch the central Mexican source of the cult, the great city of Teotihuacn.

The Tepanec king, Tezozomoc, is often referred to as the Mexican Machiavelli; Nezahualcoyotl relived many of the episodes in the life of King David of Israel; and the Mexica emperor Ahuitzotl is likened to Alexander the Great. Had the New World discovered the Old, perhaps we might have heard of Machiavelli, the Italian Tezozomoc! Then there is the blood-soaked Tlacalel, the Mexica Cihuacoatl or Snake Woman, the warrior-priest genius, who is utterly unique in the annals of world history, the man who conceived and fathered the imperial idea that sustained the growth of the Mexica empire. If a match were to be found in the Old World, surely it would have to include at least the First Emperor of China and Cromwell and many in between. Cuitlhuac, the ninth emperor or tlatoani of the Mexica, inflicted the greatest single defeat on European arms in the entire conquest of the Americas when he drove Corts and his combined Spanish and native army out of Tenochtitlan in 1520, killing over 1,200 Spaniards and 4,000-5,000 Indian allies.

The most prominent place in this book is taken by the Mexica tlatoani. They are commonly referred to as Aztecs, a name they never called themselves. Aztec means Man of Aztlan, and refers to the people that undertook the great migration that led to the founding of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, twin settlements of the Mexica on islands in Lake Texcoco. Most sources use the term Aztecs where Mexica would be more precise. I have retained Aztec in those cases where I have quoted these sources and have risked a bit of confusion on the part of the reader rather than tamper with the original source. In every other case, I use the Mexica; it is what they called themselves and was the source of the name of modern Mexico. Indeed, it was their very battle cry, O Mexica, Courage! Tenochtitlan means City by the Prickly Pear Cactus and Tlatelolco Place of Many Mounds. Inhabitants of Tenochtitlan were called Tenochca and those of Tlatelolco were Tlatelolca. Both cities were often referred to with the term Mexico, such as in Mexico-Tenochtitlan and Mexico-Tlatelolco. The ancient world of the Valley of Mexico, centred around its lakes, was called appropriately Anahuac (Near the Water). Wherever possible I have retained the spelling that most closely approximates the original personal or place names.