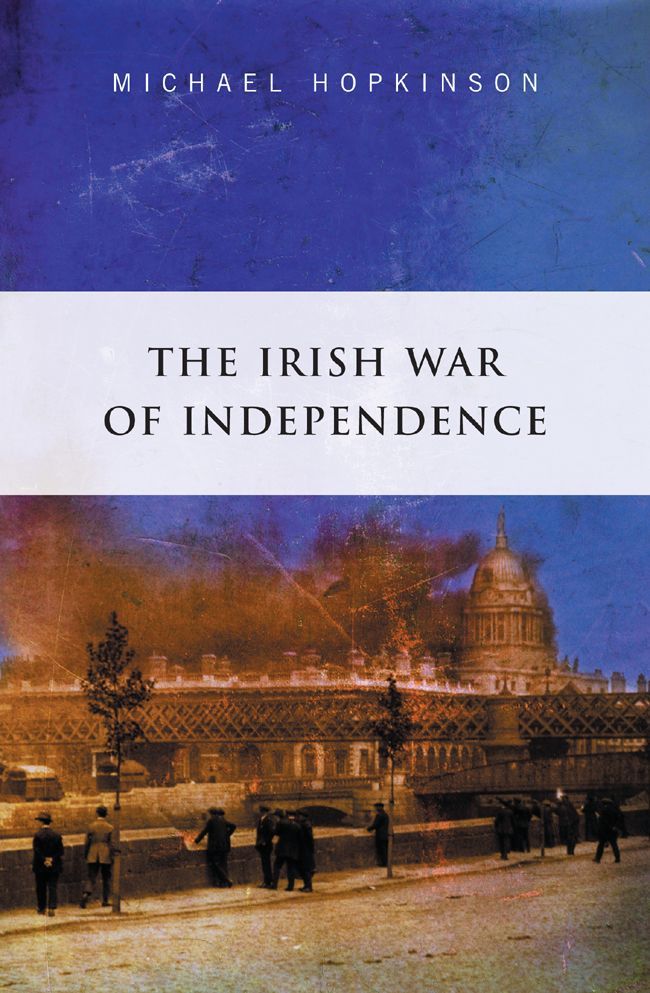

Michael Hopkinson - The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921

Here you can read online Michael Hopkinson - The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Irish War of Independence

Michael Hopkinson

Gill & Macmillan

Contents

I always think that it is entirely wrong to prejudge the past. William Whitelaw, on his arrival in Belfast as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

(By kind permission of Lady Celia Whitelaw)

Introduction

T he Irish War of Independence has provoked a massive amount of interest; IRA guerrilla warfare and Black and Tan reprisals have rivalled the issue of the British governments culpability for the Great Famine as the most emotive subject in modern Irish history. A familiar and popular story has usually been told in the form of biographies, memoirs and narrative accounts of heroic victory against the odds, of dramatic raids and ambushes, of hunger strikes and prison resistance. The Black and Tans have become the most well-known symbol for perfidious Albion in Irish communities world-wide. The best-selling books written by veterans of the conflict, notably Tom Barry in Guerilla Days in Ireland, Dan Breen in My Fight for Irish Freedom and Ernie OMalley in On Another Mans Wound, have had a huge influence on popular perception. Whole shelves in bookshops are devoted to biographies of Michael Collins with publishers blurbs talking of the man who won the War. There is still something of a national obsession with attaching blame and responsibility for the divisions which followed the conflict.

The reasons for the undying fascination are readily apparent. Biographies are a particularly colourful form of historical writing; all states, especially young ones, romanticise their founding fathers. The divisions of the revolutionary period dominated Irish politics and society for a very long time afterwards and affected historical interpretation. In his long career, Eamon de Valera always felt the need to put the record straight about the 191923 years.

To revise the traditional nationalist account of the conflict, even in the new century, is not an easy task. Sensitivities are acute: even mild correctives are easily distorted into accusations of bias on one side or the other. Both Irish and British governments have been extremely reluctant to release documents of the period. The Public Record Office at Kew in London held back a considerable amount of material at the end of the original official fifty-year closure time and since then has opened up files in a most selective fashion, inviting speculation as to the criteria used and the secrets still to be revealed, possibly in another fifty years. The mysteries of the release process have been even greater in the Northern Ireland Public Record Office where for a time some historians appeared to be given preferential treatment. In the Irish Republic, The demands of the historian are still clashing with the civil service and governmental obsession for secrecy after the passage of eighty years.

In a notorious recent academic article,

We are constantly told that Civil War politics are dead: to judge by much recent literature, Civil War history is very much alive. In this self-confident time in the history of the Irish Republic, many historians are taking an unsympathetic view of republicanism in the revolutionary era. Tom Garvins brilliant 1922: The Birth of Irish Democracy celebrates the states achievement of stability in reaction against the long-dominant neo-republican de Valera orthodoxy. Michael Laffan has referred to an almost accidental revolution and Kevin Myers keeps up a regular barrage against the nationalist consensus in his columns in the Irish Times.

In the mid-1970s, Charles Townshends The British Campaign in Ireland, 19191921 and David Fitzpatricks Politics and Irish Life, 191321 pioneered fresh scholarly perspectives on the period. Eunan OHalpin and John McColgan have laid bare the chaos and confusion of the last years of Dublin Castle rule. It remains true, however, that the central questions posed by the War are still being neglected: these relate to how and why a large measure of independence for the twenty-six counties was won, and whether that achievement was at the expense of Partition. There should be consideration of how necessary the use of violence was, and whether something akin to Dominion Status could have been won without it. Why was the British government willing in July 1921 to offer a settlement far in advance of anything offered before?

Implicit in much of the writing on the subject, both British and Irish, has been the assumption of a kind of inevitability. This applies particularly to the amount of violence used and the establishment of Partition. Hindsight can be a barrier to proper consideration of the choices faced and the mistakes made at the time. The very existence of the Free State/Republic and of the province of Northern Ireland has precluded examination of alternative outcomes from 1919 to 1921. This goes beyond the reluctance of historians to look at hypotheses, and concerns their relationship with their entire culture and upbringing.

The role of violence in the revolution, if not glorified, has been broadly accepted with little questioning. Unsurprisingly, the focus for so long was on the atrocities of Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, and less attention was paid to IRA excesses. A comforting distinction was often made between IRA violence in the 1919 to 1921 period and that in the 1970s and 1980s. The assumption was that a mandate existed for violence in the revolutionary era but not thereafter. Recently Peter Hart has brought out how much of the fighting amounted to tit-for-tat killing, in Cork as well as Belfast. What Hart says for Cork may well not apply equally to other counties, but the issue desperately needed an airing.

There was much criticism at the time of IRA activities. The Sinn Fin victory in December 1918 did not amount to an acceptance of a physical force revolution and the issue was never put to the test. It was British coercion, and particularly the reprisals from the summer of 1920, that transformed popular attitudes. The same people who had deep reservations about the IRA and its methods in 192021 later exulted over what had been achieved. In 1920, Cardinal Logue said of Michael Collins and his lieutenants: No object would excuse them, no hearts, unless hardened and steeled against pity, would tolerate their cruelty. Two years later, Logue felt that Collins had been transformed into a young patriot, brave and wise.

The part that political and passive resistance tactics played in gaining independence has only lately been accorded due importance;

The high level of violence from mid-1920 followed on decisions made by the British government to adopt a coercive rather than a conciliatory policy. Historians have underrated how near a negotiated settlement was in December 1920. The escalation of the War in late 1920 and the first six months of 1921 caused not only a terrible waste of many lives but also an appalling long-term embitterment in Anglo-Irish relations. This is the study of tragedy and is not something to glory in.

The subject of the relationship of the north-east to the War has been largely avoided. This can be explained by Partitionist attitudes on both sides of the and even justify, the intransigent policies of the Northern government. The siege mentality has extended to the historical profession. Underlying both approaches is again the assumption of the inevitability of Partition. The history of the Government of Ireland Bill was anything but predictable, and the British governments crucial backing for the hard-line Unionist policies of 192021 has rarely been sufficiently analysed. As at the end of the twentieth century, stances taken were frequently less hard-line than they appeared to be on the surface, and retrospective accounts by contemporaries tended to emphasise consistency and dogmatism as opposed to flexibility.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921»

Look at similar books to The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.