Contents

Guide

Page List

Some Recent Books by Roy Strong

Splendours and Miseries: Diaries 19671987

Scenes and Apparitions: Diaries 19882003

Coronation: From the 8th to the 21st Century

A Little History of the English Country Church

Visions of England

Self-Portrait as a Young Man

Remaking a Garden: The Laskett Transformed

Sir Portrait

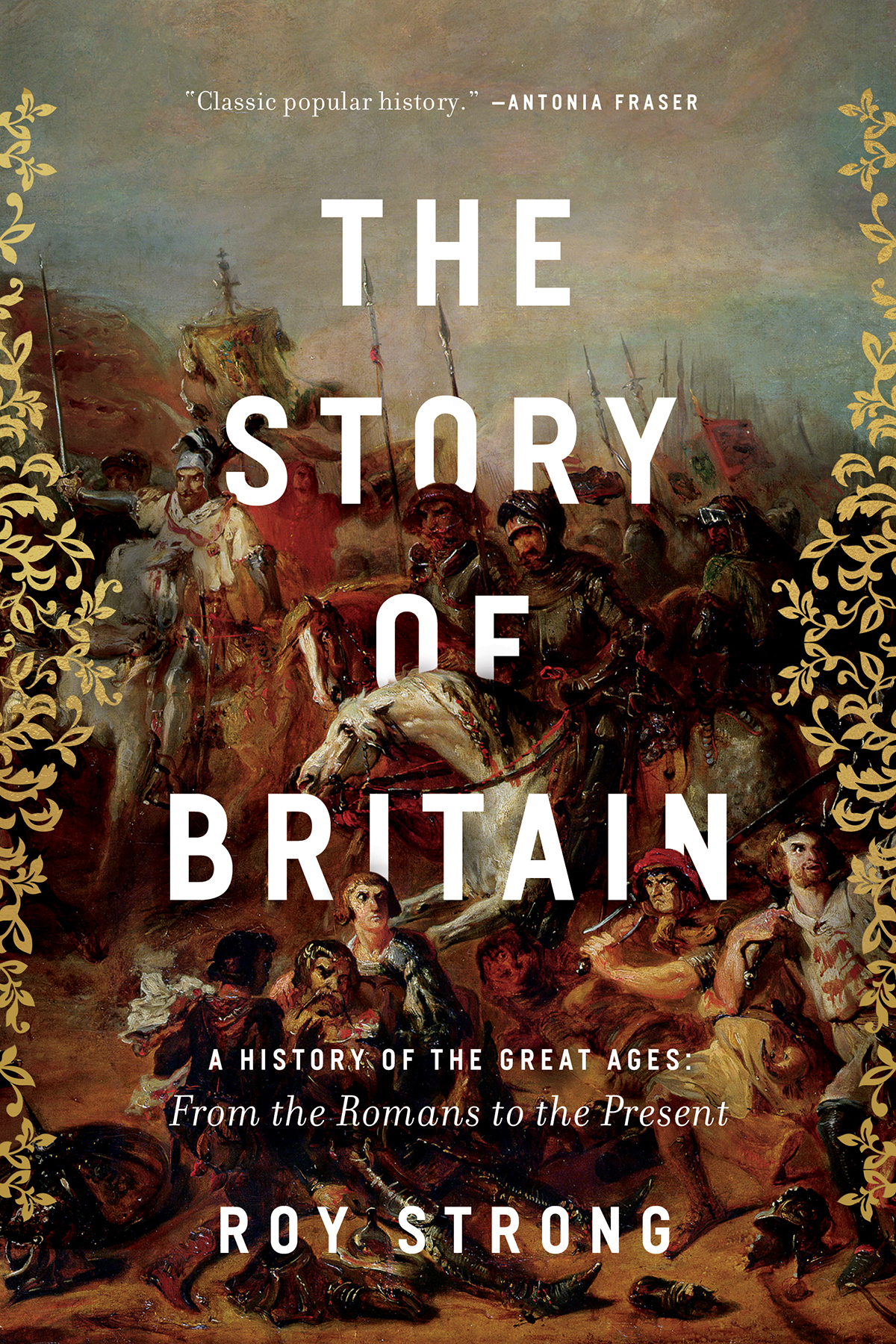

THE STORY OF BRITAIN

A HISTORY OF THE GREAT AGES:

From the Romans to the Present

ROY STRONG

Contents

In gratitude for the early inspiration of the writings of Dame Veronica Wedgwood

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winters afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding from Four Quartets

This book was written in the middle of the 1990s, when already knowledge of the nations history was fast slipping from the national psyche, especially that of the young. Story proved to be the herald of a sudden onrush of similar accounts, among them Norman Daviess The Isles: A History (1999) followed by two multi-volume accounts, Simon Schamas A History of Britain (2000) with its attendant television series, and, later, Peter Ackroyds The History of England series (201114). I have purposely read none of them.

In 1996 Story was the first single-volume narrative history of the country to have been written for decades. Those I refer to above have all been longer and heavier and, in the main, far more academic reads. Story makes no such pretension. The text, bar extending it down to the Referendum about the European Union in 2016, remains unchanged, as indeed does the premise of writing it, to provide for everyman an introductory history of our country.

The moment for Story to reappear is apposite for those who wonder what in our history led to such a dramatic decision not to become part of what amounted to a continental empire with its capital in Brussels. Knowledge of the whole sweep of our history from the departure of the Romans frames that decision within its true perspective. Whether it proves in the long run to have been a right or wrong one only history will tell.

Once again I owe a huge debt to my editor, Johanna Stephenson, and to the editorial team at Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Roy Strong

This book was the idea of my literary agent, Felicity Bryan, whose daughter Alice could not be parted from Our Island Story, a book which introduced more than one generation to the subject of British history. The present publication, when it came to be written, took on a life of its own once I started. In fact it was unique in my writing career in almost telling me as I went along the direction it wanted me to go in. So it evolved into what one hopes might be an introduction for anyone of any age to the history of the island which the Romans first designated as Britain. In it, I hope, the reader will find his bearings in what has been conceived as a sustained narrative whose imperative has been less when and how than why.

Such a publication cannot ever be anything other than idiosyncratic. No writer can wholly shed his predilections and prejudices however hard he tries. So far as I can I will define these so that when and if encountered, they can be discounted. By the time this book is published I shall be sixty, which means that my earliest memories are those of the Second World War and of the fervent patriotism necessary for a nation under siege. I would describe myself as a conservative with a small c by instinct, and a practising Christian of a variety which might be labelled progressive Anglican Catholic. My education took me to the Warburg Institute, whose orbit is the history of the classical tradition, so I am firmly a European in both my intellectual make-up and by political conviction. I am also a product of my own age, a lower middle-class boy who made his way upwards through hard work and scholarships to join the ranks of the professional classes who now control the destiny of the country.

There is nothing particularly original about this book. Its span is so enormous that it could never be anything other than a synthesis of syntheses. It is built with gratitude on the work of others and where they disagree, as all academics do, I have inevitably, for a book of this general and introductory nature, had to settle on a compromise. Only in the case of the modern period have I indicated that historians are divided in their views. All I have attempted to achieve is to present a fair and balanced picture of successive ages bound together by a strong narrative which encourages the reader to turn the page and read on.

For those periods in which human beings emerge as distinct personalities with influence over events I have introduced the occasional biography in an attempt to set people within time. Up until Chaucer biography is virtually an impossibility, apart from kings, saints and statesmen, and even then it is difficult. In our own century I was equally defeated until I recalled Sir Isaiah Berlin once saying, No great people any more. That indeed may be true in what is the age of the common man, but it may equally reflect my own inability to find them. The choice of the biographies is mine, but I have tried to alight upon people who changed the direction of things.

This is the first time that I have read the entire history of Britain since I was an undergraduate in the 1950s, having inhabited in my academic work the cultural pastureland of Tudor and early Stuart England. British history has changed enormously since then, particularly by widening its terms of reference beyond the confines of politics and economics. That wider vision has been enriching and I have attempted to incorporate it, and indeed in doing so found the occasional biography a wonderful vehicle for demonstrating how the cultural and intellectual history of this country cannot be separated from the tide of political events. But I have avoided compiling a bibliography of the huge number of books I read and consulted, since any such list in a book of this nature is bound to be unhelpful for specific purposes.

History and its teaching has been very much in the public eye as I have been writing but I have avoided becoming entangled in things like the National Curriculum, preferring to pursue my own solitary path. In the same way I have deliberately avoided reading any other general history of Britain for fear of any influence on my own pen. The guiding light has been the belief that a country which is ignorant of its past loses its identity.

The project has been a shared passion, fired and urged ever onward by my editor. An author is blessed by few remarkable editors in a lifetime but Julia MacRae is one of them. My voyage down the centuries has not been a lonely one. Whenever I have shown signs of flagging she has picked me up and put me firmly back at the prow of the ship of British history and urged me to sail on. Words cannot express my sense of gratitude to her. Publishing is teamwork and in the case of a large project like this must call for a commitment and vision in which everyone has a part to play. I am deeply grateful to all of them. Douglas Martin, the designer, has been obsessed as we all have with ensuring that the book is put together not only to look handsome in terms of design, but above all to entice the reader to read.