Contents

Guide

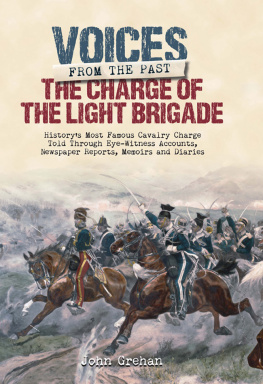

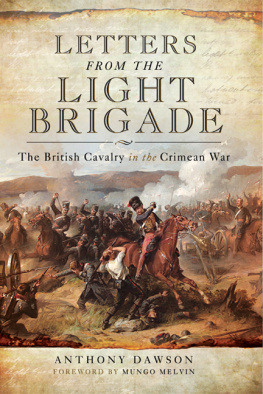

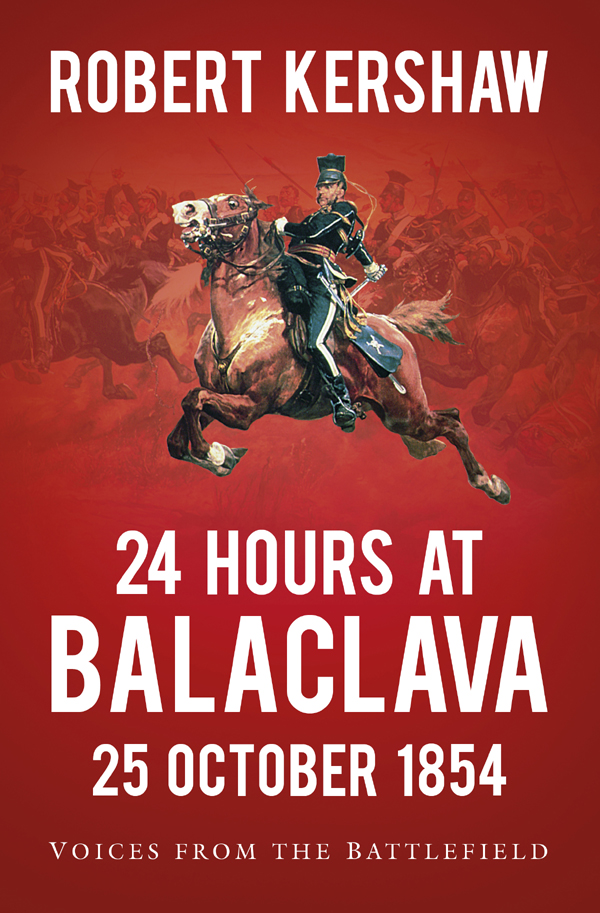

Cover illustration: Charge of the Light Brigade, Balaclava, 25 October in 1854 (colour litho) by Richard Canton Woodville Jr (Bridgeman Images)

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Robert Kershaw, 2019

The right of Robert Kershaw to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9159 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Maps produced by Geethik Technologies

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Sevastopol

Midnight to 4.30 a.m.

Balaclava Night

Midnight to 3.30 a.m.

Them Rooshans

3 a.m. to 6 a.m.

The Fight for the Turkish Redoubts

5.30 a.m. to 9 a.m.

Eight Minutes of Cut and Slash

8.55 a.m. to 9.15 a.m.

Decisions

9.30 a.m. to 11.10 a.m.

The Ride of the Six Hundred

11.13 a.m. to 11.20 a.m.

Running the Gauntlet

11.20 a.m. to 11.35 a.m.

Stand-Off

11.35 a.m. to Midnight

INTRODUCTION

In 1854 Britain and France were fighting to save poor little Turkey, the crumbling Ottoman Empire, from the menacing Russian bear. Tsar Nicholas I thought it his holy duty to extend the power of the Empires Orthodox Church as far as Constantinople and Jerusalem. The Ottomans were ailing, and Imperial Russia, led by Nicholas these past twenty-seven years, knew it, and sensed opportunity. The British, ostensibly defending Turkey against Russian bullying, were actually promoting rivalry against the Tsar in Asia while extracting free trade and preferential religious treatment from a crumbling Ottoman Empire. Revolutionary secularism motivated France, under Napoleon III, ironically promoting the Catholicism that underpinned his reign. He aimed to restore overseas influence and prestige squandered during Napoleons wars. Russian expansionism was a threat.

Six weeks before, the Allies landed in the Crimea to invest the Russian Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol. The Battle of Alma, fought six days earlier, was an unexpected defeat for the Russians and resulted in the rapid encirclement of Sevastopol. It was the ninth day of the siege.

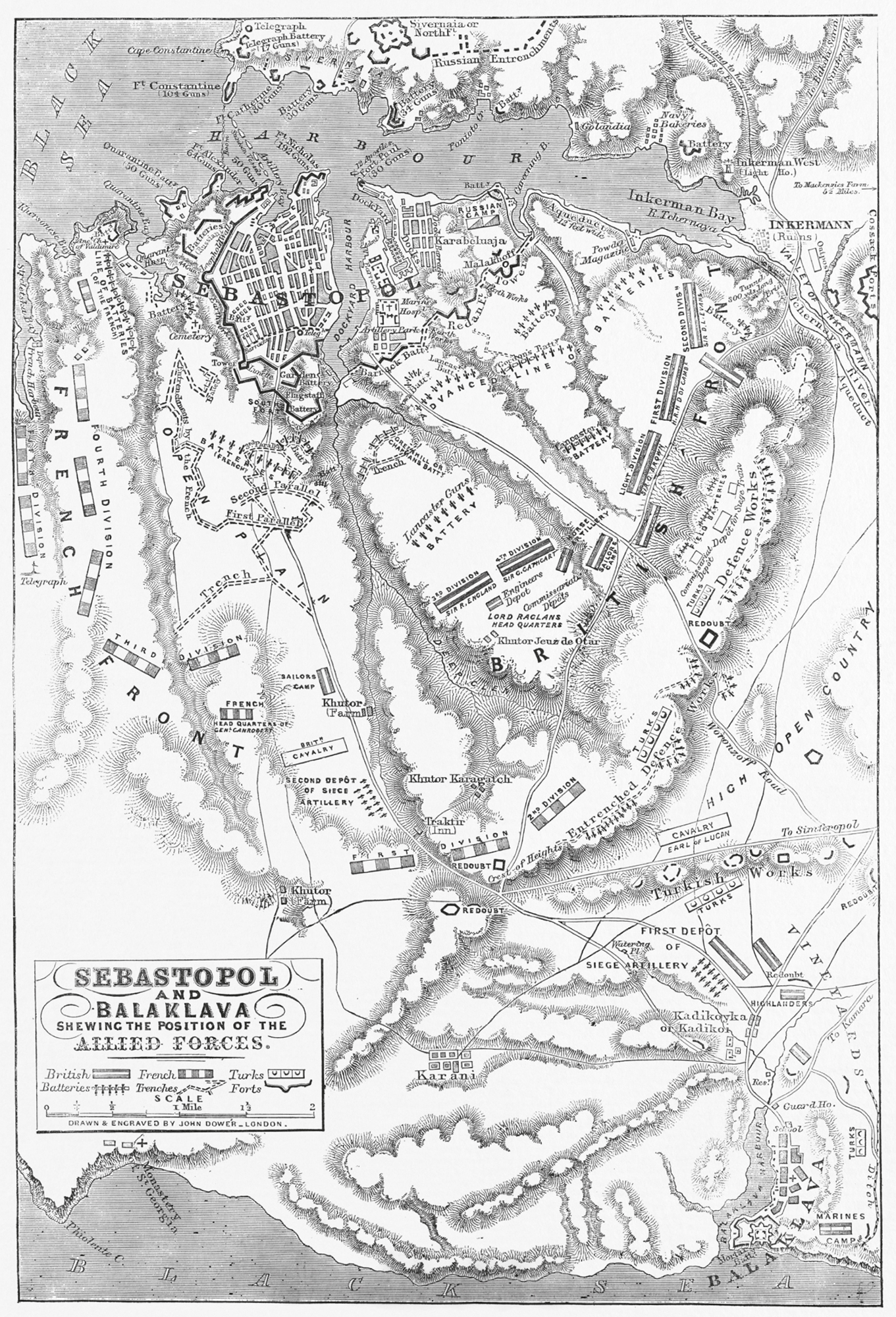

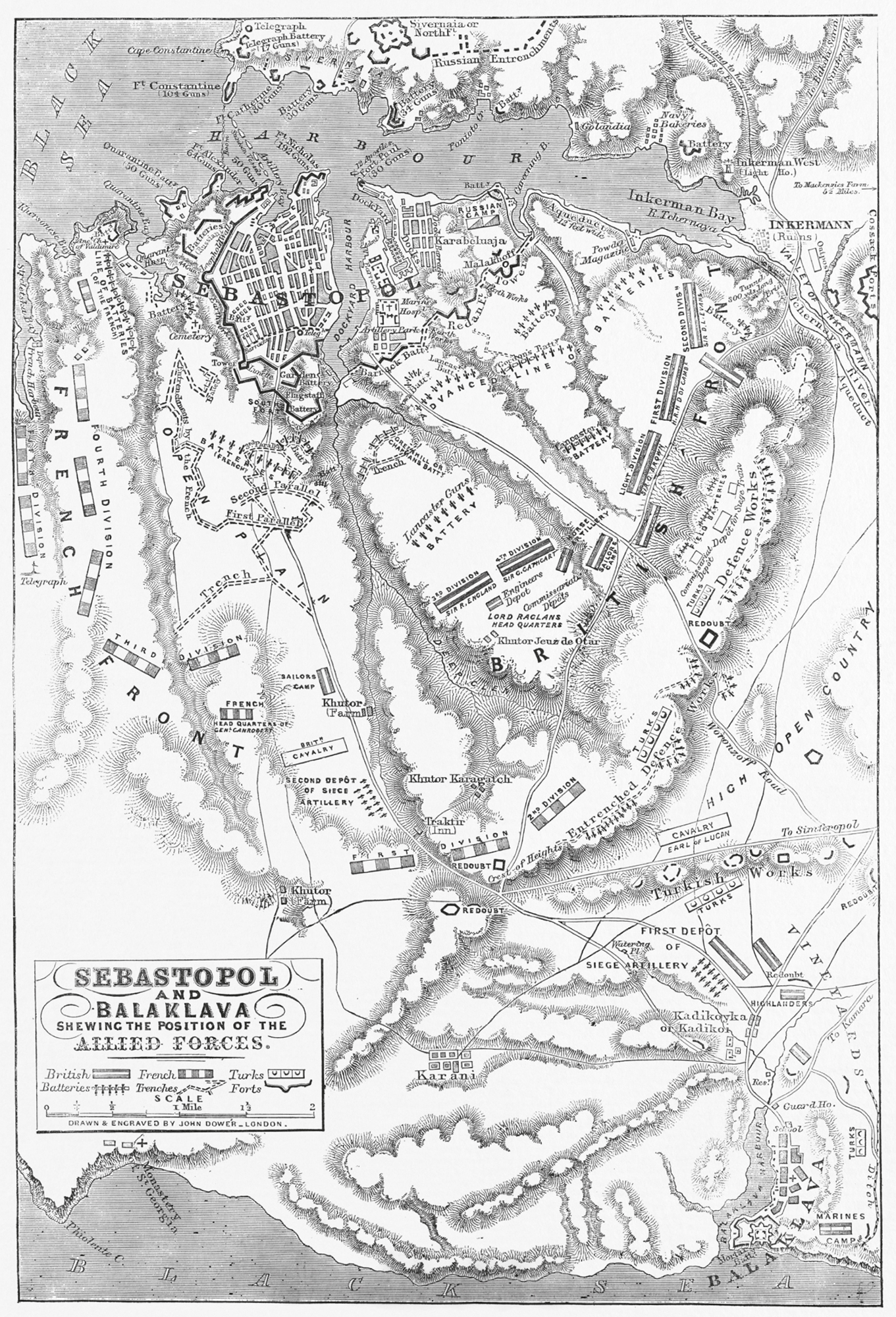

A contemporary nineteenth-century map of the siege lines around Sevastopol. The French were to the left (west) and the British on the right (east).

An intangible Russian menace to the Allied rear had yet to materialise, despite frequent cries of wolf from outlying pickets. So when the first cannon boomed out from the murk, way to the east and rear, senior Allied commanders were jerked into frenetic activity. The unlikely had occurred. A Russian army was knocking on the back door of Sevastopol and on the cusp of severing the British umbilical supply line to its logistics base at Little London, Balaclavas harbour, absolutely packed with shipping.

Twenty-four hours of high drama followed. Before mid morning, seven minutes of cut and slash saw 900 British heavy cavalry see off and scatter more than 2,000 Russian horse. At the same time, 400 charging Russian cavalry were deflected by a thin red streak of Scottish infantry from entering Balaclava harbour. Then, within two hours of achieving near victory, the British squandered it by recklessly sending 664 British light cavalry spurring down the Valley of Death, as immortalised by Alfred Lord Tennysons famous poem. Half the British cavalry in the Crimea was destroyed. These epic clashes, which took up less than an hour of fighting, were to occupy a future iconic and reverential place in popular British psyche. The failed charge inspired epic poetry and literature and is still portrayed in Hollywood movie recreations today.

War correspondent William Howard Billy Russell witnessed the events from a grandstand viewpoint on the Sapoune Heights. Writing for the prestigious Times newspaper, Russells dramatic eyewitness coverage moved hearts and souls back home. Russell rode on the back of his influential newspaper in a new era of steamship and telegraph and could get his dispatches back to England in three weeks. There was no censorship, so the facts were as accurate as Russell could see. Times readers were electrified by the accounts. Before, all that had been traditionally available to the public were official military dispatches. William Russell was the civilian eyewitness on the spot. His electrifying account of the events at Balaclava on 25 October 1854 arrived at Victorian breakfast tables within nineteen days.

Tennysons famous poem The Charge of the Light Brigade was published in The Examiner on 9 December, way ahead of the arrival of the salient facts. Russell subsequently edited this dispatch, but when Tennyson wrote the poem, the Times reported 800 cavalry had been engaged and only 200 returned. The Illustrated London News claimed only 169 had got back. In fact, between 661 and 664 light cavalry charged, of which 299 fell, 103 of them mortally, but the myth was already set. Someone had blunderd was Tennysons not unreasonable assumption on reading the early dispatches, but it was too early to objectively assess recriminations at this stage.

Tennyson wrote classic Victorian poetry, inspired by Russells heroic prose. The whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame, Russell wrote, echoed by Tennysons stormd at with shot and shell. Only with Russells subsequent edits did it become increasingly apparent that Tennysons cannon to right of them, cannon to left of them, cannon in front of them had indeed been the case. Russell later wrote that the cavalry were exposed to an oblique fire from the batteries on the hills on both sides as well as to a direct fire of musketry.

When I walked the ground recently with local guide Tanya Zizak, it became apparent that this was probably intermittent fire from three different directions, and unlikely to have been simultaneous. Both men viewed the spectacle at considerable distance: Russell from the Sapoune Heights 2 miles away and Tennyson from his study at Farringford on the Isle of Wight. Clinically removed from the visceral carnage by his position on the Heights, William Russell indulged in a poetic flow as: with a halo of flashing steel above their heads, and with a cheer which was many a noble fellows death cry, they flew into the smoke of the batteries. This flowery text is replicated by Tennyson, who immersed himself in a dramatic story of knightly figures on horseback. This was the noble six hundred, riding into the valley of death. Tennysons grandson Charles later remembered that the poem was written at a single sitting, after reading Russells dispatch, barely six weeks after the event.