All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted,

in any form or by any means,

without prior permission from the publisher or copyright holder.

Text Edward M. Spiers, 2010

Foreword Ian Knight, 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Originally published in 2010 in the United Kingdom by

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

This edition published in South Africa in 2010 by

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS (PTY) LTD

P O Box 33977

Jeppestown

2043

ISBN 9781868424153

with

Frontline Books

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited, 47 Church Street,

Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

UK ISBN: 9781848325944

Typeset by Palindrome

in ITC Galliard 10/13pt

Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books

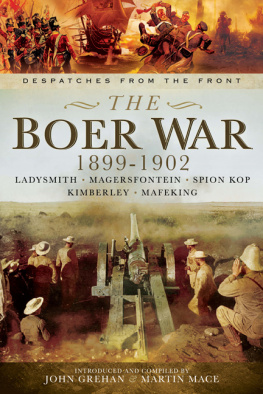

The Anglo-Boer War of 18991902 was undoubtedly the greatest challenge faced by the British empire during the nineteenth century.

At the very apogee of imperial pomp and pretension, at a time when Britains reputation as an economic, industrial and military power was still largely unrivalled around the world, the army that had painted great swathes of the map British red, from Canada to Afghanistan and India to New Zealand, appeared suddenly powerless in a series of embarrassing clashes fought in obscure African locations against a relatively small citizen militia of white farmers. The repercussions of the conflict would prove to be enormous, shaping not only the extraordinary twentieth-century history of southern Africa paving the way for the post-war emergence of Afrikaner nationalism and the rise and fall of the apartheid state but impacting upon Britains relations with its European rivals, and offering the British army harsh but valuable lessons on the very eve of the First World War. Indeed, for Britains professional soldier elite undeniably experienced as they were the Anglo-Boer War proved to be something of a final chapter in a complex and often painful evolution that had taken them, within the reign of a single monarch, from an essentially Napoleonic institution, fighting conventional battles in close-order formations and wearing red coats, to a recognisably modern one, groping towards an understanding of all-too contemporary counter-insurgency techniques.

While it is true that the war that broke out at the southern tip of the African continent in October 1899 between the British and the Boer republics of the Orange Free State and Transvaal had much to do with immediate and local tensions and in particular the conflicts that had arisen between an essentially conservative and inward-looking Transvaal government and British capitalist interests intruding there in the wake of the discovery of gold in large quantities in the Witwatersrand in 1886 it was in truth part of a much broader contest, a struggle between two very different forms of European colonialism that had emerged in southern Africa across more than two centuries.

In 1652 the Dutch East India Company had established the first European settlement at the Cape of Good Hope. At that time, the Dutch had little interest in the African hinterland the Company specifically barred its settlers there from travelling beyond its boundaries into the interior and was primarily concerned with providing a facility to provision and repair its ships on the long maritime haul to the far more profitable Dutch concerns in the Indies. Britain too, of course, relied on its imperial possessions in India and the East as a motor to drive its imperial expansion, and for 150 years Britains largely amicable relationship with the Netherlands allowed British ships access to the Cape way-station. With the shuffling of long-established alliances in Europe that came first with the Revolutionary and then Napoleonic Wars against France, however, Britain had found that she could no longer take the security of the Cape sea-route for granted, particularly once Napoleon had conquered the Netherlands and established the pro-French Batavian Republic. With Dutch possessions falling under Napoleons control and raising a very real threat that the sea-route to India around the Cape might be cut, Britain had opted for direct action. In 1806 a British invasion fleet had landed at the Cape and dispersed Batavian forces in a battle fought out on the sand-dunes within sight of Table Mountain. The British took control of the colony and would remain the dominant regional power for almost exactly a century.

It was not long, however, before the European inhabitants of the Dutch settlement, many of whom were in fact French religious refugees from Europe, came to realise that Britains interests had little in common with their own. Whereas Britain was a metropolitan power, looking out at the world through networks of economic and political influence of which the Cape was but a link in an extensive chain, the Cape settlers had largely turned their backs on the outside world. Although a common sense of identity and nationhood would elude them until the twentieth century it came, ironically, as a result of their ultimate defeat in the Anglo-Boer War they had already come to think of themselves increasingly as a distinct people, not Dutch but Cape Dutch or, latterly, Afrikaners white Africans. For the most part they were simply known by the Dutch word for a farmer or country person, boer. Accustomed to living tough and self-reliant lives on remote farms in a harsh and often unforgiving landscape, buoyed up by a stern religious faith and a sense of racial superiority that kept them aloof from the indigenous inhabitants, they looked instead to find a role for themselves in Africa, and were soon disillusioned with the more liberal approach towards racial interaction and frontier security adopted by the British administration. By the 1830s Boer discontent was sufficient to spur more than 12,000 men, women and children to abandon their farms and livelihoods, to place whatever possessions they could in their ox wagons, and emigrate wholesale beyond the limits of British authority in search of a new life in the interior of southern Africa.

The so-called Great Trek reshaped the political geography of the region. The Trekkers progress was marked by a series of brutal conflicts with the robust African societies who had occupied the land before them, and while it led ultimately to the creation of the two republics it also framed the parameters of future rivalry with the British. Underpinning initial British concerns that Boer actions should not impact upon their strategic interests in the region, destabilising their borders or encouraging involvement with rival world powers, was a much deeper conflict in which both sides increasingly strove to secure control over the land and its resources a conflict that saw African groups trapped uncomfortably in between. The British had attempted to reassert their authority in the 1840s, a series of small actions, largely forgotten today, fought out in the Free State and in Natal, and while they had been content, in the end, to relinquish their claims to the interior, they had secured their hold over the eastern coast, leaving the Trekker republics resolutely landlocked.

In the end, however, it was the unexpected realisation that southern Africa possessed immense mineral wealth that had pushed the two groups into a knock-down conflict. With the discovery of diamonds north of the Cape in the 1860s, the British had adopted, for the first time, a forward policy designed to secure their control over the area as a whole. When, in 1877, the Transvaal Republic, beset by conflicts with its African neighbours, had seemed on the verge of bankruptcy, the British had intervened and annexed it; the Boer response was to sit quietly while the British went on to defeat the neighbouring Zulu kingdom and then, in December 1880, to rise in revolt. Stung by a series of defeats in the field the senior British commander, General Sir George Colley, was killed at the disastrous battle of Majuba on 27 February 1881 the Liberal administration of Prime Minister Gladstone agreed to abandon the Transvaal once more to the Boers, subject only to vague claims to suzerainty.