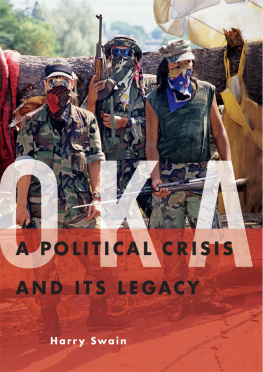

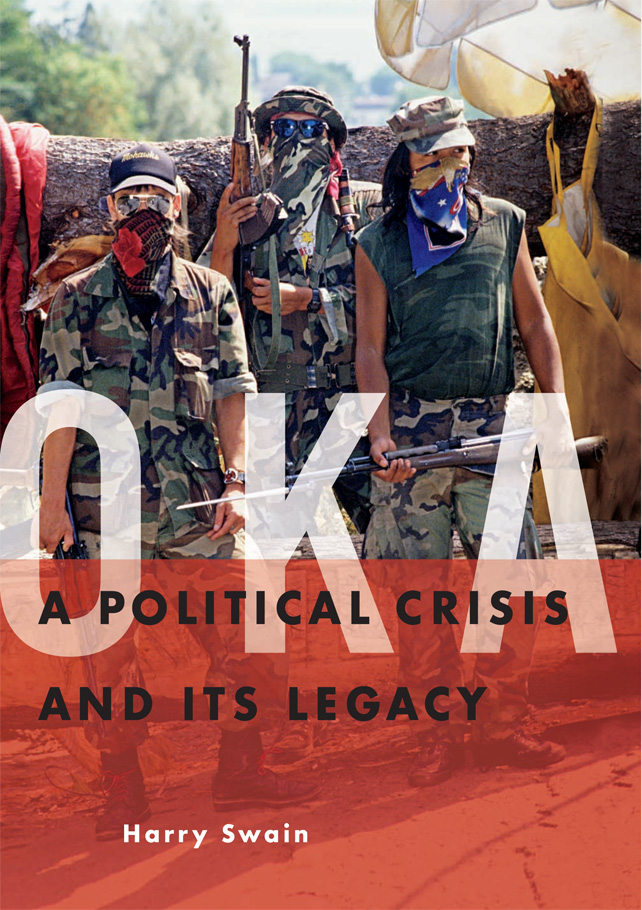

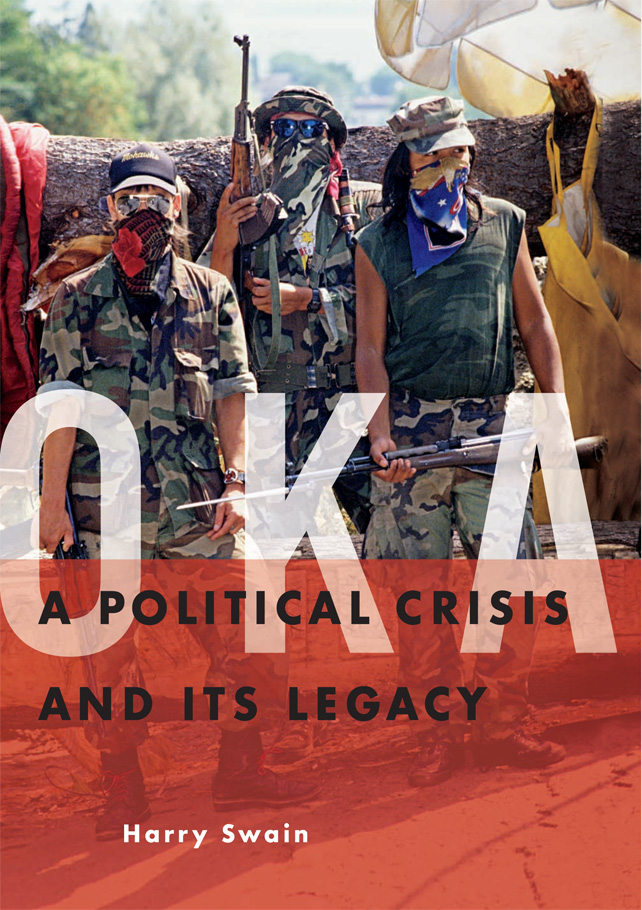

O K A

A POLITICAL CRISIS

AND ITS LEGACY

Harry swain

OKA

Copyright 2010 by Harry Swain

10 11 12 13 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form

or by any means, without the prior written consent of the

publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing

Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-429-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-642-5 (ebook)

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Jacket design by Peter Cocking

Text design by Jessica Sullivan

Photo research by Pronk & Associates

Jacket photograph Christopher J. Morris/CORBIS

Maps by Eric Leinberger

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Text printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer paper

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada

Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the

Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax

Credit and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book

Fund for our publishing activities.

In recognition of the discipline and restraintof the 5th Mechanized Brigade, and of Jenny Jack,which saved many lives

CONTENTS

T HIS BOOK is written to supply a perspective on the Oka crisis of 1990, from the point of view of someone who worked inside the federal government. To date it has been mostly journalists telling the story, as in the colourful and readable accounts of Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera on Kanesatake (People of the Pines) or Rick Hornung on Akwesasne (One NationUnder the Gun), though there have been a few personal memoirs, notably those of John Ciaccia and Doug George-Kanentiio. Bruce Johansens excellent Life and Death in Mohawk Country investigates what happened during the civil war at Akwesasne. Alanis Obomsawin produced a dramatic two-hour movie, Kanehsatake:270 Years of Resistance, for the National Film Board that captures some of the emotions on the Mohawk side of the barricades. The Montreal Gazette and the Globe and Mail, as well as radio and television broadcasters, followed the story closely once the gunfire began. To one degree or another, these first drafts of history tend to be sympathetic to the participants and critical of governments and their agents in the police and the armed forces. An exception is a lengthy chapter in a book entitled The Real Worlds of CanadianPolitics: Feather and Gun: Confrontation at Oka/Kanesatake by Robert Campbell and Leslie Pal, a careful account that uses the Oka story to call attention to the need for deep changes in public policy. Recently the first comprehensive voice from the military side has been heard, with the publication of Timothy C. Winegard's Oka: A Convergence of Cultures and the Canadian Forces.

In the summer of 1990, I was the federal deputy minister of Indian Affairsthe latest, in the eyes of some, in a long line of heavy-handed Eurocentric colonial administrators. The advantage of the job was that it gave me a unique view of events, the drama and excitement of which I hope comes through to readers. The downside is equally obvious: as a player, and a representative of a government that had a decided position on many of the issues, nothing I have written will, nor should, be seen as neutral or scholarly. My own views were not always those of the government I served, however, and I have not tried to suppress them here. What happened at Oka is part of the story of Canada, and, more generally of the collision of European and native cultures over the last five centuries or so. There are a number of Mohawk people (by no means all) who will nod their heads, perhaps in private, at much of what I have to say.

I spent my civil service career dealing with microeconomic policy in one form or another, except for five years in the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). In the end, economic policy became humdrum for me, even boring. The direction of virtue is always apparent for economists, even if you never get there. In the aboriginal world, and I suspect in the area of social policy generally, the path to truth, justice and right thinking is much less apparent, and conventions of language can conceal yawning gaps in meaning. Every now and then during my time in Indian Affairs I would stumble, in the middle of a conversation in an ostensibly shared language, into some epistemological abyss. The sudden realization, for example, that the malign spirit in the snowdrift over there to whom an Inuit speaker was matter-of-factly referring was not just a figure of speech but an empirical realitywell, that was a new thought to a southern Euro-Canadian. Working across cultural boundaries can be exhilarating. I think of my five years in Indian Affairs as the best years of my working life.

One of my first lessons there, as this book reflects, was that contemporary events have two-hundred-year-old tails. No part of the departments business makes sense without understanding that, and people with no taste for history should not work there. Trying to impose the latest nostrum from a management school text is a recipe for failureand, in Indian country, an occasion for mirth. In this context, the old Historical Section at DIAND, now the Research and Analysis directorate, is a national treasure, and over the years its people have helped all parties to understand better just where in the grand currents of history they are swimming at the moment. The first two chapters of this book are intended to offer a similar perspective for readers. Every word in them bears on the events of 1990and of 2010.

History veers from drama to farce to tragedy and back again. People under the pressure of great events are never simply noble, silly, scared, humourless or accident-prone. They are human: they are all of these things. What makes behaviour in a crisis so interesting is the compression of events. There is little time to check facts, untangle mysteries, assess new players or invent new modes of institutional response.

So it was with the story of Oka. All sorts of people were drawn into the affair, many surprised to be there, all of them with fragmentary histories of past entanglements, and all of them with views that corresponded imperfectly to the world and to the views of the other players. Ignorance, uncertainty and risk waited at every turn. Speed and strain affected events. The Canadian Army understood better than anyone the costs of haste and the value of sharing information with adversaries. Slowing things downbuying timewas often the most constructive step anyone could propose.

I NDIAN is the erroneous European name for the original inhabitants of the Americas. It is the term used by the department I worked for and the law I administered. The word Indian has become incorrect in certain quarters, even slightly antique. But it continues to be used, notably among those inhabitants of the Prairies who regard themselves as treaty Indians. Other terms have their problems too. Aboriginal, a term widely used in Australia, is a historically recent import preferred by some, but, like native, its scope can be too broad for precision. First Nations is popular, but it is a collective term, and it tends to be synonymous with the old bands of the

Next page