Copyright 2019 by Jeremy D. Popkin

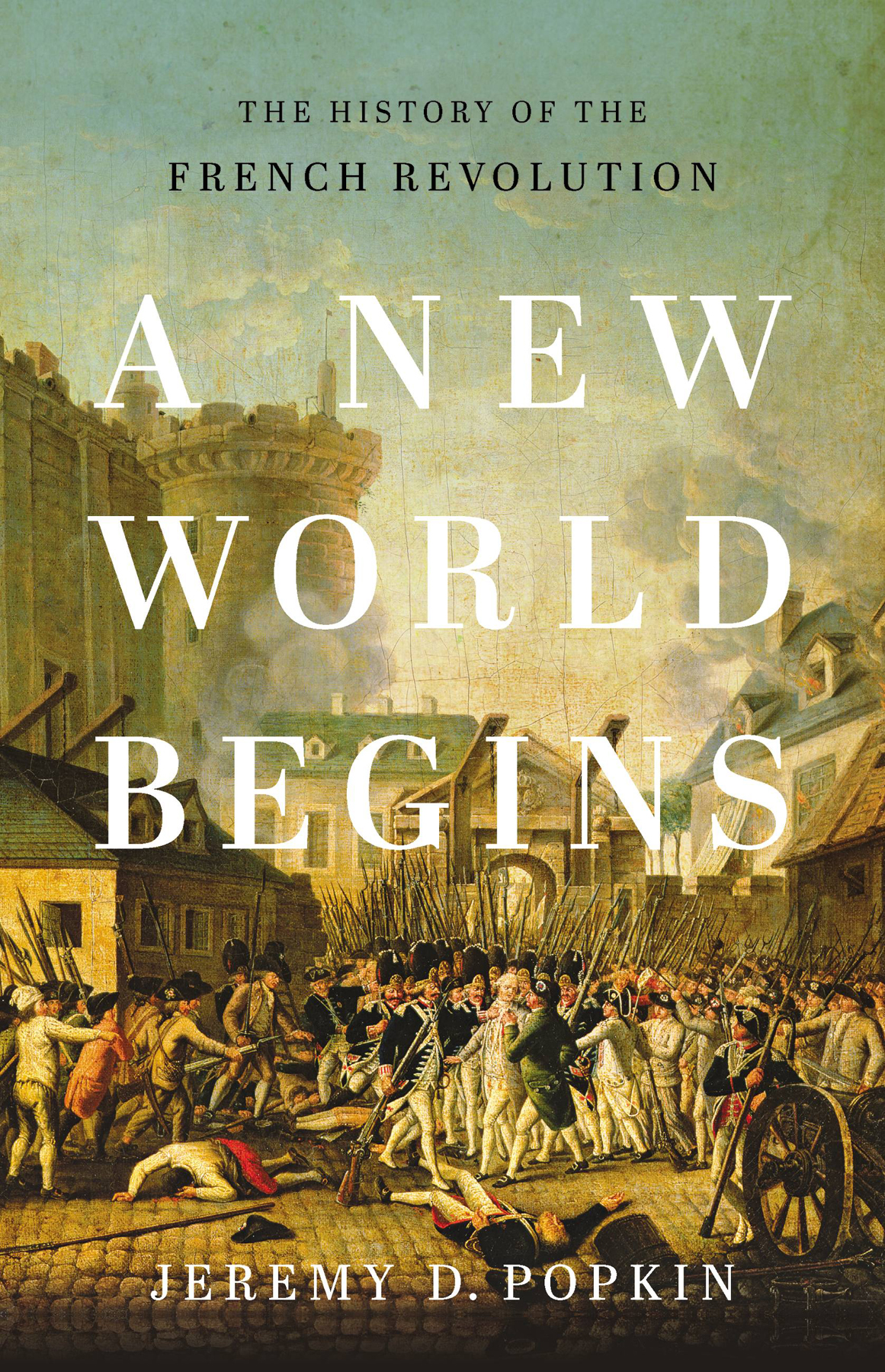

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images: The Taking of the Bastille, 14 July 1789 (oil on canvas), French School (18th century) / Chateau de Versailles, France / Bridgeman Images; MaxyM / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: December 2019

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Popkin, Jeremy D., 1948- author.

Title: A new world begins : the history of the French Revolution / Jeremy D. Popkin.

Other titles: History of the French Revolution

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019101| ISBN 9780465096664 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780465096671 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: France--History--Revolution, 1789-1799.

Classification: LCC DC148 .P665 2019 | DDC 944.04--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019101

ISBNs: 978-0-4650-9666-4 (hardcover), 978-0-4650-9667-1 (ebook)

E3-20191025-JV-NF-ORI

Discover Your Next Great Read

Get sneak peeks, book recommendations, and news about your favorite authors.

Tap here to learn more.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

A History of Modern France

From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography

A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution

You Are All Free: The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery

Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection

A Short History of the French Revolution

Revolutionary News: The Press in France, 17891799

To my parents, Richard H. Popkin (19232005) and Juliet Popkin (19242015), who inspired me with a love of learning, and my grandmother Zelda Popkin (18981983), who made me want to be a writer.

The force of things has perhaps led us to do things that we did not foresee.

Louis-Antoine de Saint-Just, 1794

A T THE END OF 1793, A PRINTER IN THE A MERICAN FRONTIER SETTLEMENT of Lexington, Kentucky, as far away from the French Revolution as any point in the Western world, published The Kentucky Almanac, for the Year of the Lord 1794. Along with a calendar and weather forecasts for the coming year, the almanacs main feature was a poem, The American Prayer for France. Addressing the deity as the Protector of the Rights of Man, the anonymous poet implored him to make thy chosen race rejoice, / and grant that KINGS may reign no more. His message was clear: the outcome of the French Revolution mattered, not just to Frances heroes brave, her rulers just, but to all those around the world who believed that human beings were endowed with individual rights and that arbitrary rulers should be overthrown. At the same time, however, the poets words showed how hard it was to interpret the upheaval that had started in France in 1789 from a distance. Even as the Kentucky author implored Gods protection for the Revolution, the revolutionaries were suppressing religious worship in France, and as he

Today, more than two hundred years since the dramatic events that began in 1789, the story of the French Revolution is still relevant to all who believe in liberty and democracy. Whenever movements for freedom take place anywhere in the world, their supporters claim to be following the example of the Parisians who stormed the Bastille on July 14, 1789. Whoever reads the words of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, published in August 1789, immediately recognizes the basic principles of individual liberty, legal equality, and representative government that define modern democracies. When we think of the French Revolution, however, we also remember the violent conflicts that divided those who participated in it and the executions carried out with the guillotine. Likewise, we remember the rise to power of the charismatic general whose dictatorship ended the movement. As I sit in my study in Lexington today, making sense of the French Revolution is as much of a challenge as it was for the anonymous author of the Kentucky Almanac.

When I began my own career as a scholar and teacher in the 1970s, the memory of the worldwide student protest movements on university campuses in the 1960s was still fresh. Those movements had inspired interest in the French Revolution, which seemed to stand alongside the Russian Revolution of 1917 as one of the great examples of a successful overthrow of an oppressive society. Ironically, the understanding of the French Revolution in those years of upheaval seemed largely fixed: virtually all historians agreed that it had resulted from the frustrations of a rising bourgeois class determined to challenge a feudal old order that stood in the way of political and economic progress.

By the time I participated, along with researchers from all over the globe, in commemorations of the bicentennial of the French Revolution in 1989, the situation had changed drastically. The communist regimes in Eastern Europe were now tottering, and the fact that the French Revolution had inspired the Soviets was a reason to ask whether Frances upheaval had foreshadowed totalitarian excesses more than social progress. The polemical essays of a dynamic French historian, Franois Furet, challenged the orthodoxy that had dominated study of the Revolution; among other things, he appealed to scholars in the English-speaking world to turn to the subject with fresh eyes.

The decades since 1989 have brought even more questions about the French Revolution to the fore. In 1789, the French proclaimed that all men are born and remain free and equal in rightsbut what about women? At the start of the American Revolution, John Adamss wife, Abigail, famously urged him in a letter to remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Some of the women of the periodthe playwright and pamphleteer Olympe de Gouges, the novelist and salon hostess Madame de Stal, the backroom politician Madame Roland, and the unhappy queen, Marie-Antoinettebecame prominent public figures and left ample records of their thoughts. Others took part in mass uprisings or exerted influence through their daily grumbling about bread prices. Under the new laws on marriage and divorce, some women welcomed the possibility of changes in family life; others played a key role in frustrating male revolutionaries efforts to do away with the Catholic Church. A history of the French Revolution that does not remember the ladies is incomplete.