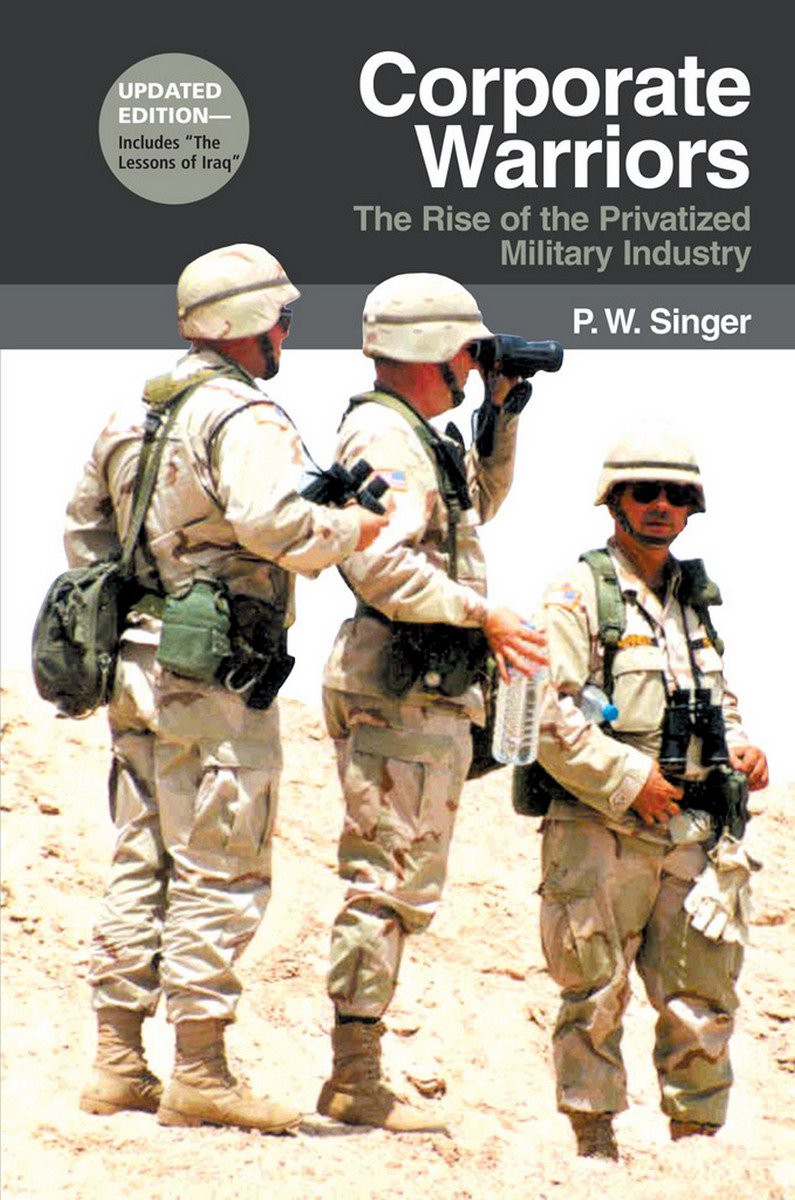

Corporate Warriors

A volume in the series

CORNELL STUDIES IN SECURITY AFFAIRS

edited by Robert J. Art, Robert Jervis, Stephen M. Walt

A full list of titles in the series appears at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu.

Corporate Warriors

The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry

UPDATED EDITION

P. W. Singer

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca and London

Copyright 2003 by Cornell University

Postscript copyright 2008 by Cornell University.

All rights reserved. Except for brier quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof', must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press. Sage House, 512 Fast State Street, Ithaca. New York 14850.

First published 2003 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell paperbacks, 2004 First printing, updated paperback edition, 2008

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Singer, P. W. (Peter Warren)

Corporate warriors: the rise of the privatized military industry / P. W. Singer.

p. cm. (Cornell studies in security affairs)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-743(5-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Defense industries. 2. Military-industrial complex.

3. Privatization. 4. Defense industriesUnited States.

5. Military-industrial complexUnited States. 6. Privatization United States. 7. United StatesMilitary policy. 1. Title.

II. Series.

HD9743. A2S56 2003

338-4'7355dc21

2003000456

Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www. cornellpress. cornell. edu.

Paperback printing

Contents

Preface

It was only indirectly that I first stumbled across the phenomenon of private companies offering military services for hire. I had never heard of such a thing, until I joined a U. N. -supported project in 1996, researching the postwar situation in Bosnia. As we interviewed regional specialists, government officials, local military analysts, and peacekeepers in the field, it soon became evident that the entire military balance in the Balkans had become dependent on the activities of one small company based in Virginia, (Military Professional Resources Incorporated)MPRI. I visited the firms regional offices, located in a nondescript building along the Sarajevo riverfront, where the firm coordinated the arming and training of the Bosnian military.

The members of the firm were polite and generally helpful, but the ambiguity between who they were and what they were doing always hung in the air. They were employees of a private company, but were performing tasks inherently military. It just did not settle with the way we tended to understand either business or warfare. However, there they were, simply doing their jobs, but in the process altering the entire security balance in the region. I was struck by this seeming disconnect, between the way we normally view the world of military affairs and the way it actually is, and wanted to learn more. I spent the next years following just that path, interviewing hundreds who either work in the industry or are close observers of it and even spent a period working at the Pentagon, helping to oversee one of the firms contracts.

In the time since, both the industry and the firm I visited have certainly grown up. MPRI was recently bought by a Fortune-500 firm, while other companies offering military services have been discussed in many of the world's most prominent newspapers, radio, and TV outlets. 1 Beyond the general media, the idea of private businesses as viable and legitimate military actors has also begun to gain credence among a growing number of political analysts and officials, from all over the political spectrum. 2 Their activities have caught the attention of legislative officials in a number of countries and led to the submission of several bills covering their actions. 3 An international forum of African heads of states advised their use in certain situations, as did the commander of the U. N. operation in Sierra Leone. 4 Even Sir Brian Urquart, considered the founding father of U. N. peacekeeping, advocated the hire of such firms.5 Another sign of emerging market maturity is that a new industry trade association, International Peace Operations. Association (IPOA), recently formed to lobby on behalf of military firms.6

The essential point is, that in the time since my first encounter with what I began to think of as Corporate Warriors," this private military industry is no longer so small or obscure. However, for all its growth, our understanding of it still remains greatly limited.

WHAT IS MISSING!

Part of why the military industry remains an enigma is that although numerous newspaper and magazine articles have been written on the activities of such firms, most have been long on jingoistic headlines and short on earnest examination. Within academia, there have been a few articles and reports that have introduced and described some of the firms, but the broader field remains largely uninformed.7 Most studies of the firms have been generally descriptive rather than integrative. None have addressed the industry broadly or comparatively and our knowledge of the industry still has not been advanced in any systematic manner.8

The reason is that the limited research done so far on military firms has focused on case studies of individual companies or of single conflicts where they were present, most often in Africa where they made their first appearance. Analysts have also tended to treat the more mercenary type as miniature armies in isolation. They have not placed them in a context with either similar companies that offer other types of military services or with general business models. A typical description is the erroneous statement that the client list of these firms is limited to weak states with corrupt leaders.9

The result is a vacuum of established facts and a lack of understanding of this industry or the firms within it. There are no universally accepted definitions of even the most widely used terms.10 No framework of analysis of the industry exists, no elucidation of the variation in the private military firms activities and impact, no attempts at examining the industry as a whole, and no comparative analyses.

Equally dangerous is that much of what has been written about these firms is noncritical, with very little examination of the industry from an independent perspective. The topic is exceptionally controversial, with peoples livelihoods, reputations, and even perhaps the industrys ultimate legality dependent on how academia and policymakers meld to understand it. Unfortunately, the small amount of qualitative analysis that has been done is often highly polarized from the start, aimed at either extolling the firms to the extent of even comparing them to messiahs," or condemning their mere existence.11 In turn, these biased findings are often misused by the firms or by their opponents in pushing their own agendas.12

Thus, years after my first contact with the industry, the entire topic still remains murky to the general public, not only in the arena of known facts about the firms and their operations, but also in the lack of explanatory and predictive concepts and independently assessed policy options. This book is intended to resolve these issues, both the growing vacuum in theoretical and policy analysis of the industry, and the limitations of prior approaches.

Next page