The chariot

2600 BCAD 83

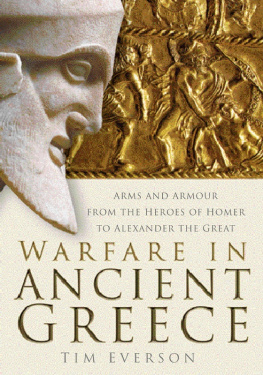

The Sumerian city-states of southern Mesopotamia, which flourished in the third millennium BC, provide us with the earliest evidence of disciplined formations of heavy infantry, forerunners of the phalanx, conducting far-flung military campaigns in the beginnings of empire.

The armies of these city-states were also the first to use wheeled vehicles as mobile firing platforms. As depicted in a lyre found in the royal cemetery at Ur in southern Mesopotamia (in use around 26002000 BC), they were inelegant solid-wheeled wagons hauled by donkeys, or possibly the larger onager, an animal usually resistant to domestication. Perhaps these beasts of burden were mule-like hybrids, now extinct.

The animals are yoked to a draft pole and controlled by reins that run through a ring mounted on the pole. Two men ride in the chariot, a driver and a soldier wielding a spear or an ax. A quiver of spears projects from the front of the chariot. There is no indication of how these vehicles would have been deployed in battle. With their four heavy wheels, they would have been cumbersome, and the onagers would have presented an inviting target. It is likely that they provided a chauffeur service to the battlefield rather than maneuvering on it.

Logistics The early centuries of the second millennium BC saw significant innovations in the art of war: bentwood construction produced a lighter, more maneuverable chariot fitted with spoked wheels; and the development of the composite bow introduced a rapid-fire missile delivery system from the fast-moving chariot. Nevertheless, the construction of the chariots, the breeding and management of the horses, and the training of the chariot driver and warrior, were an expensive business requiring a major logistical underpinning.

To keep large bodies of charioteers in the field, armies needed substantial numbers of wheelwrights, chariot builders, bow makers, metalsmiths and armorers. On campaign, still more men were needed to manage the spare horses and repair damaged vehicles. Chariotry became a significant symbol of military might. The great powers of the dayEgypt, the Hittites in modern central Turkey, and the Assyrians in what is now Iraq, all became practiced exponents of chariot warfare.

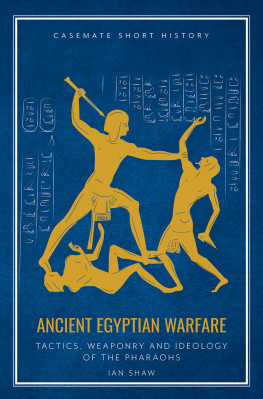

Egypt From about 1600 BC, Egypt turned the powerful new combination of horse, lightweight chariot and composite bow into a weapon of territorial expansion. Egypts massive manpower and material resources stood behind an army numbering tens of thousands that could project Egyptian power well beyond its now stabilized borders.

Straddle car

Surviving clay models provide evidence of smaller two-wheeled chariots and the so-called straddle car, consisting of an axle with two wheels, and a saddle set on a vertical post on the draft pole above the axle. We do not know how these lost war wagons were employed, but they provide ample evidence of mans unquenchable desire to devote considerable resources to the development of weapons systemsthe origins of successive arms races from the ancient world to the present day.

Driving up the east Mediterranean littoral in about 1485 BC, Pharaoh Tuthmosis III found his path blocked by a coalition of local forces around the city of Megiddo (now in northern Israel), which commanded the route into southern Syria. Tuthmosis used speed and surprise to overcome the defenders of Megiddo and bottle them up in the city, which surrendered after a seven-month siege.

Egyptian chariots played a key role in the Battle of Megiddo, arriving at the critical point to shatter the federation of local forces opposing Tuthmosis. Chariotry was a high-value weapon that could only be launched at the crucial moment in a battle. Its task was to launch a drive that would break the enemy infantry. Once the tide of battle had been turned, the role of chariotry was to pursue the fleeing enemythe phase in any engagement when most losses in men and equipment occur, and a reverse can be turned into a rout.

All the princes of all the northern countries are cooped up within it. The capture of Megiddo is the capture of a thousand towns.

From Tuthmosis inscriptions

Battle of Qadesh The Hittite empire, originally based in central Turkey, provided the next barrier to Egyptian expansion. At the beginning of the 13th century BC, Pharaoh Ramses II led his army into western Syria to reduce the city of Qadesh, which blocked the path to confrontation with the Hittites. The two sides met at the Battle of Qadesh (1274 BC). The Egyptians were initially thrown into disarray by a Hittite chariot attack, and the situation was only retrieved by the arrival on the scene of a second Egyptian force. Qadesh was a battle of attrition, involving thousands of chariots, from which both armies emerged badly mauled. Hostilities between the two powers were ended by a nonaggression pact.

The Persians In the middle of the first millennium BC, the Persians refined the art of chariotry with scythed wheels. The Greek soldier-historian Xenophon (c.425c.335 BC) wrote that scythed chariots were introduced into the Persian army by Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BC), although the fourth-century historian Ctesias of Cnidus places their origins earlier. Indian sources mention scythed chariots being used in the campaigns waged by the Mauryas against the Vriji confederacy during the reign of Ajatshatru (494467 BC). However, we do not know whether scythed chariots were an Indian invention adopted by the Persians or a Persian invention adopted by the Indians.

And Solomon gathered chariots and horsemen: and he had one thousand four hundred chariots, and twelve thousand horsemen, which he placed in the chariot cities and with the king at Jerusalem.

Chronicles 1: 14

Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BC) employed scythed chariots in large numbers. However, the days of the war chariot were now numbered. At the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC) the army of Alexander the Great simply opened its lines to let the Persian chariots career through before attacking them from the rear.

The Celts In northern Europe, the Celts of the third century BC used chariots to fight against cavalry. When fighting from his two-horse chariot, the Celtic warrior threw his javelin first and then alighted, in Homeric fashion, to fight with his sword. Julius Caesar, who invaded Britain in 55 and 54 BC, left a description of British chariot warfare: Firstly they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot.

The Romans encountered Celtic chariots at the Battle of Mons Graupius, fought in northeast Scotland in AD 83. The Roman senator and historian Tacitus noted that the plain between the two armies resounded with the noise and with the rapid movement of chariots and cavalry. The chariots had little effect: Meanwhile the enemys cavalry had fled, and the charioteers had mingled in the engagement of the infantry.

the condensed idea

The chariot was the ancient worlds tank

| timeline |

|---|

| c.26002000 BC | Sumerians use wheeled vehicles as mobile firing platforms |

| c.1600 BC | Egypt combines chariot, horse and composite bow in empire-building army |

| 1485 BC | Battle of Megiddo |

| 1274 BC | Battle of Qadesh |

| c.500 BC | Scythed chariots appear in India and Persia |

| 55 and 54 BC | Julius Caesar invades Britain |

| AD 83 | Battle of Mons Graupius |