ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to the individuals and organizations that have shared

their time, knowledge, and passion with us. This book could not

have been constructed without their help.

Kermit Hummel

Chris Benedetto

Christopher Reiter

Robert Balcius

William & Ann Payson

Special thanks to members of

Co. H, 3rd Arkansas Infantry Regiment (3rd Rgt., ANV):

Scott Dyer, Tom Backus, Kris King, and Alec Franzoni

2012 by Denis Hambucken and Matthew Payson

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages.

Photographs, illustrations, book design and composition by Denis Hambucken

Editing by Lisa Sacks

Historic typefaces by Walden Fonts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data have been applied for.

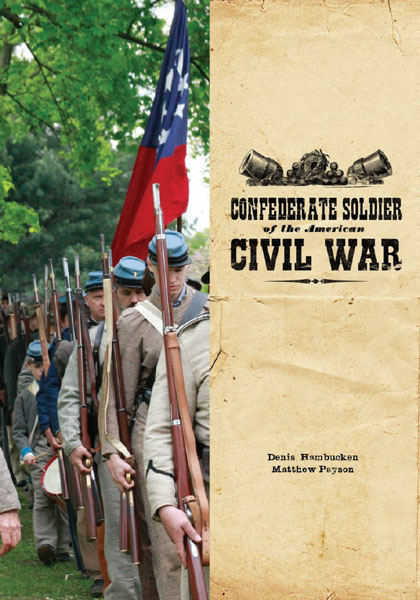

Confederate Soldier of the American Civil War

978-0-88150-977-9

Published by The Countryman Press, P.O. Box 748, Woodstock, VT 05091

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES

THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES

Sam Watkins, who enlisted as a private in the 1st Tennessee regiment, wrote that the common soldier of the Civil War was the one who did the shooting and killing, the fortifying and ditching, the sweeping of the streets, the drilling, the standing guard, picket and vedette, and who drew (or was to draw) eleven dollars per month and rations, and also drew the ramrod and tore the cartridge... The majority of those who fought, and who felt deeply for their part in the struggle, were average citizens: farmers and store owners, laborers and schoolteachers. They all held their own opinions of the bigger issues that faced their generation but most were more concerned with providing for and protecting their families than in joining the fiery debates ripping through statehouses and the U.S. Congress.

While slavery was at the center of the division between North and South, ultimately, it was not what motivated the majority of soldiers on either side. In his book The Women of the South in War Times, Matthew Page Andrews reflects the prevailing Southern sentiment when he defines the conflict as: a struggle between an agricultural people of the South seeking free trade with the world, and a commercial and manufacturing people in the North who sought, and obtained, high protective tariffs, under which the North was able to buy cheaply the raw material of the South, while the South was compelled to pay high prices for the manufactured articles produced in the North. William M. Dame, who served as a gunner, wrote about the average soldiers motivation: With those men it was to defend the rights of their states to control their own affairs, without dictation from anybody outside; a right not given, but guaranteed by the Constitution.

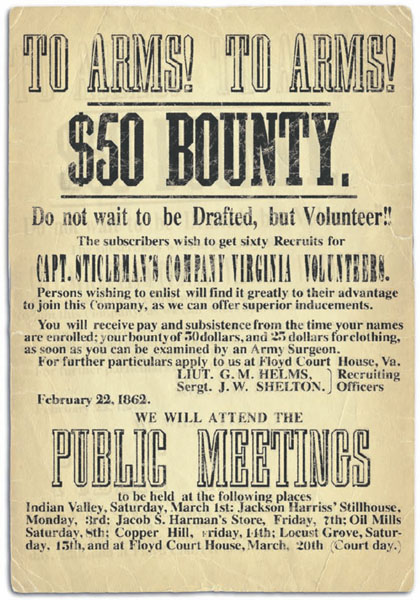

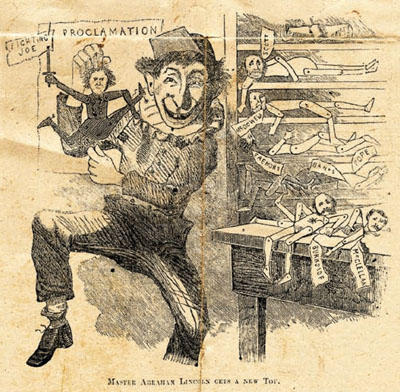

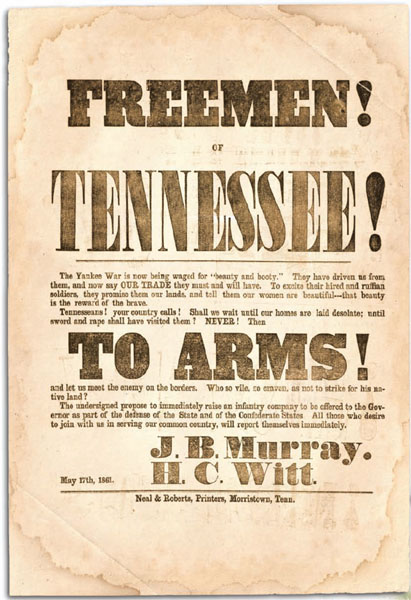

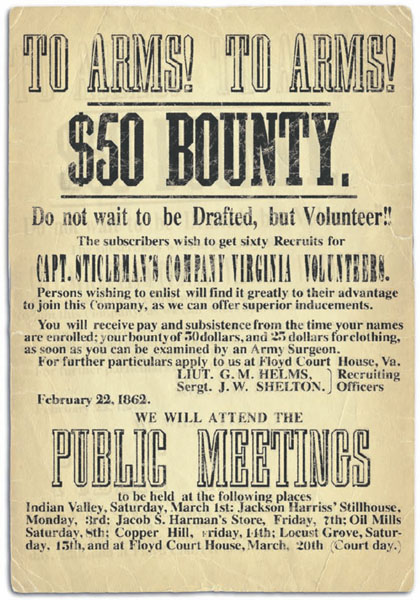

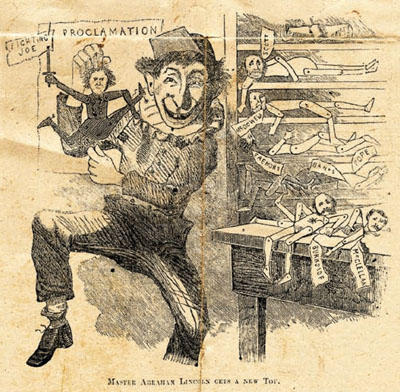

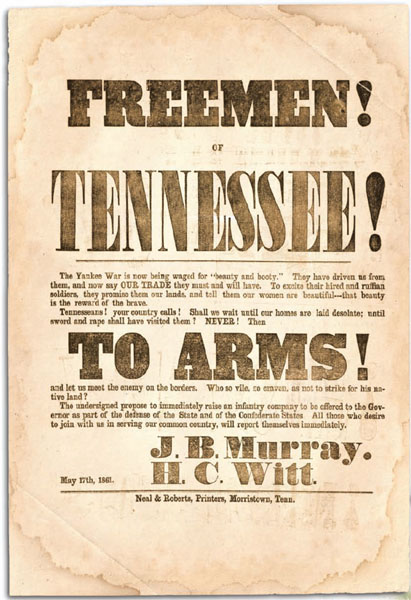

In April 1861, the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, a Federal fort in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, ignited the long-simmering divisions between North and South. Within a day after Union troops surrendered the fort, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 troops to quell the great rebellion. Within every state, citizens were compelled to choose sides and stand for the Union or for the independence of states, with the firm belief that their own side stood for rightness and justice.

To the Union soldier of the U.S. forces, it was a fight to preserve the Republic as one nation, and to retaliate against those who had fired on the American flag at Fort Sumter. The shell-torn flag was carried through the streets of New York City like a fallen martyr, prompting thousands to answer President Lincolns call to enlist. To the Confederate soldier it was a fight for self-determination, the same cause for which his grandfathers had fought in the American Revolution, and to defend his home from the Federal armies that were marching south to, as President Lincoln put it, crush the insurrection. William Fletcher, who was a private in the 5th Texas regiment, wrote that both North and South were proving, from their viewpoint, the justness of their position by both the Bible and the Constitution, and from the preachers views, the Lord was with us for he could prove it by the Bible; while the politician would quote some of the wording of the Constitution, and say: God and all civilized nations are with us. It was the politician and the preacher, he felt, who had pushed the country to a point where none could see a way to resolve their grievances except in war. And so it was bloodnothing else but blood and we surely spilled it.

From Maryland to Florida, Missouri to Texas, citizens enlisted in state defense forces, while thousands more (some even coming from Northern states) made their way to Richmond, Virginia, to defend the new Confederate capital, only 100 miles from Washington, D.C. Among them were scores of officers and soldiers of the U.S. military who returned home to serve in defense of the South, and who, along with cadets and professors from Southern military academies, helped to train and organize the thousands of new volunteers.

By July of 1861, Union armies under General MacDowell were marching south toward Richmond, Virginia. On the 21st of that month, just north of Manassas Junction, Virginia, Confederate forces under Generals Beauregard and Johnston confronted the Union Army in the first infantry battle of the war. At the end of that day, MacDowells army was in full retreat to Washington, leaving several thousand dead and wounded men behind.

With such a decisive victory for the South, many felt that, for the most part, the conflict was over. To them all that remained was to serve out the rest of their twelve-month enlistments guarding the border and awaiting a settlement of peace. By the end of 1861 the conflict, though far from resolved, had come nearly to a standstill. The war was over now, wrote Watkins, describing the common attitude as his regiment went into camp near Staunton, Virginia. Our captains, colonels and generals were not hard on the boys; in fact, had begun to electioneer a little for the Legislature and for Congress... whiskey was cheap, and good Virginia tobacco was plentiful, and the currency of the country was gold and silver. They spent much of their free time visiting local towns, saloons and gambling halls. For much of the army, that fall was spent building log huts for the winter, and activity fell mostly to basic military drill, manning fortifications, and dealing with the boredom of camp life.

Next page

![Fawcett - How to lose the Civil War : [military mistakes of the War between the States]](/uploads/posts/book/92687/thumbs/fawcett-how-to-lose-the-civil-war-military.jpg)