This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

The World at War is a trademark of FremantleMedia Limited.

Licensed by FremantleMedia Enterprises.

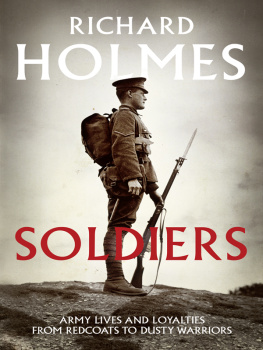

Richard Holmes has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

FOREWORD

BY SIR JEREMY ISAACS

All film-makers shoot more footage than they use; The World at War was no exception. We always knew we had more good stuff than could conceivably be crammed into twenty-six hours of commercial television each 'hour' only fifty-two minutes, thirty seconds long, to be precise. We never kept a strict tally, but I'd guess the ratio of newsreel printed to that used was about fifteen to one; for interviews it was higher still, well over twenty to one. The first assemblies of strong, relevant material ran at over three hours; hard choices always had to be made to get each episode down to transmittable length.

We shot, from the outset, for the series and for the record. What was omitted was left, not on the cutting-room floor, but in the Imperial War Museum (IWM). Thames Television, at its all-round best the finest of the ITV franchise holders, sturdily footed the bill.

In a way, the money Thames spent was public money. The ITV companies, fifteen of them, enjoyed near monopolies, in their own areas, of television advertising revenue. In February 1971, after years of pressure, the government agreed to change the basis of the special levy on ITV franchises the price they paid for their monopoly from a tax on revenue to a tax on profit; their income would no longer be taxed at source. The condition was that the companies spend, and be seen to spend, more on programmes. I went at once to my bosses at Thames and suggested we make a history of the Second World War. A few weeks later, on AprilFool's Day 1971, we started work. Our principal collaborator was the IWM; its director, Noble Frankland, our historical adviser. It was a condition of the contract that all the original footage we shot be deposited in the IWM's archive. There it has lain to this day.

The World at War's key ingredients were the image and the word, newsreel and eye-witness interview. Music and narration held all together. Some programmes went short of pictures; there is little visual record of war at sea, or acts of resistance, or of genocidal gas-chambers. Those episodes relied on interviews. One episode, on Stalingrad, used no witnesses; no Red Army veterans would face the camera in 197273, at the height of the Cold War. But those were the exceptions. For the most part we reckoned to use newsreel and interviews, split fifty-fifty; so only about thirteen hours of interview made it to the screen.

Some voices are heard only for a moment. An American paratrooper, who dropped in France before the D-Day landing, tells us: 'I was afraid. I was nineteen, and I was afraid.' I hear him still.

Others, particularly the leaders, talked at greater length. What interviewer, researcher or producer, facing a Supreme Commander, a presidential aide, the Foreign Secretary, an SS General, could resist seeking an overview, a tour d'horizon? It might serve in several programmes, after all. As you read these pages, remember The World at War's interviewers; they did a fine job.

The World at War took fifty of us three years to make: we talked to hundreds of survivors and printed a million feet of film. When it was finished the final episode screened in May, 1974 we made three lengthy specials from the ample surplus to hand. Then, the team broke up; each moved on to other things. Making The World at War took over our lives, but we never thought of transferring what we'd done to other media. Now, triumphantly, the voices we recorded speak again on the printed page. Rereading the transcripts today, I am impressed by how successfully, in skilled hands, they transfer to print; vivid, articulate, revelatory.

Television history is narrative history. Several interpretations of a strategic decision may be worth considering, but the film-maker must choose one, and stay with it. On the page, there is time and freedom toreview the options. On complex issues, a wealth of opinion is easily displayed, and differing experiences related. In commissioning this oral history, Ebury Press has taken a visionary initiative. Richard Holmes has done a superb job of selection, and of organising the mass of material. On many topics he presents a broader and more nuanced account than did TV's linear narrative. His book deserves a vast readership. I salute him.

Jeremy Isaacs describes the making of The World at War in Look Me in the Eye: A Life in Television, published by Little Brown 2006.

INTRODUCTION

I always rather dislike being called a television historian, preferring to see myself as an historian who enjoys talking about his subject: in that sense, at least, television, books and lectures are simply different parts of the same process. Yet there is no doubt that I am exactly of an age to have been profoundly influenced by television history. The BBC series The Great War appeared in my last year at school, and I can well remember watching some of its episodes on a tiny television in the worn and fusty setting of a house-room at my boarding school. It introduced the real complexities of its subject to an audience that either knew nothing about the war or had accepted at face value some of the more egregious comments that then passed for fact. Despite the best endeavours of Dr Noble Frankland, then Director of the Imperial War Museum (whose generosity in reducing the charges that the museum might otherwise have charged for copyright material had made the series possible in the first place), it took some extraordinary liberties with its use of visual images, blurring the boundaries between reconstructed and actuality sequences. It nevertheless deserves the much overused description 'landmark', and, as Dr Frankland has written, 'it launched the idea of history on screen'.

In 1973, almost a decade later, when I was in the early stages of my career as a military historian, pecking away at my doctoral thesis with the one-finger typing that kept the makers of Tipp-Ex in profits, the Thames Television series The World at War appeared. I was captivated at once. The poignant rise and fall of Carl Davis's music; the montage of extraordinary facial photographs in the pre-title sequence, each successively burned awayto reveal another, like pages of an album seared by heat, and the mellifluous enunciation of Laurence Olivier, all had me enthralled even before I had properly watched a single episode. Once I began to watch, I was hooked. The breadth of the 26-episode series, shaped and sustained by the directing brain of Jeremy Isaacs, the series producer, was simply breathtaking. This was no narrowly Eurocentric story, but just what its name implied, the Second World War from background to legacy, and from the freezing waters of the North Atlantic through the sands of the Western Desert to the jungles of Burma. What struck me then was the remarkable quality of the eyewitnesses who had been interviewed, and the way in which the words of the men and women who had 'fought, worked or watched' were put at the very centre of the television treatment. For instance, I shall never forget hearing Christabel Bielenberg, a British woman married to a German lawyer, describing the rise of Hitler: suddenly the events of 193336 were not something that had happened long ago and far away, but a personal story being told by a familiar voice. She was to call her book