Cover copyright 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

A FEW YEARS AGO, I accidentally caused a small outbreak of misinformation. On my commute to work, a friend who works in tech had sent me a stock photo of a group hunched over a table wearing balaclavas. We had a running joke about how news articles on computer hacking would often include staged pictures of people looking sinister. But this photo, below a headline about illicit online markets, had taken things much further: as well as balaclavas, there was a pile of drugs, and a man who apparently wasnt wearing any trousers. It seemed so surreal, so inexplicable.

I decided to tweet it. This stock photo is fascinating in so many ways, I wrote, pointing out all the quirks in the image. Twitter users seemed to agree, and within minutes dozens of people had shared and liked my post, including several journalists. Then, just as I was starting to wonder how far it might spread, some users pointed out that Id made a mistake. It wasnt a stock photo at all; it was a still image from a documentary about drug dealing on social media. Which, in retrospect, made a lot more sense (apart from the lack of trousers).

Somewhat embarrassed, I posted a correction, and interest soon faded. But even in that short space of time, almost fifty thousand people had seen my tweet. Given that my job involves analysing disease outbreaks, I was curious about what had just happened. Why did my tweet spread so quickly at first? Did that correction really slow it down? What if people had taken longer to spot the mistake?

Questions like these crop up in a whole range of fields. When we think of contagion, we tend to think about things like infectious diseases or viral online content. But outbreaks can come in many forms. They might involve things that bring harmlike malware, violence or financial crisesor benefits, like innovations and culture. Some will start with tangible infections such as biological pathogens and computer viruses, others with abstract ideas and beliefs. Outbreaks will sometimes rise quickly; on other occasions they will take a while to grow. Some will create unexpected patterns and, as we wait to see what happens next, these patterns will fuel excitement, curiosity, or even fear. So why do outbreaks take offand declinein the way they do?

THREE AND A HALF YEARS into the First World War, a new threat to life appeared. While the German army was launching its Spring Offensive in France, across the Atlantic people had started dying at Camp Funston, a busy military base in Kansas. The cause was a new type of influenza virus, which had potentially jumped from animals into humans at a nearby farm. During 1918 and 1919, the infection would become a global epidemicotherwise known as a pandemicand would kill over fifty million people. The final death toll was twice as many as the entire First World War.

Over the following century, there would be four more flu pandemics. Before COVID-19 emerged, people would sometimes ask me what will the next pandemic look like? Unfortunately its difficult to say, because even previous flu pandemics were all slightly different. There were different strains of the virus, and outbreaks hit some places harder than others. In fact, theres a

We face the same problem whether were studying the spread of a disease, an online trend, or something else; one outbreak wont necessarily look like another. What we need is a way to separate features that are specific to a particular outbreak from the underlying principles that drive contagion. A way to look beyond simplistic explanations, and uncover what is really behind the outbreak patterns we observe.

Thats the aim of this book. By exploring contagion across different areas of life, well find out what makes things spread and why outbreaks look like they do. Along the way, well see the connections that are emerging between seemingly unrelated problems: from banking crises, gun violence and fake news to disease evolution, opioid addiction and social inequality. As well as covering the ideas that can help us to tackle outbreaks, well look at the unusual situations that are changing how we think about patterns of infections, beliefs, and behaviour.

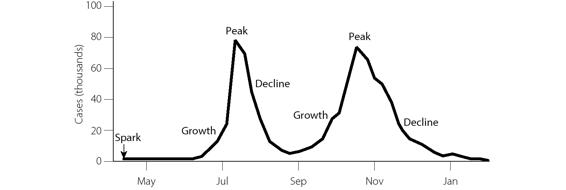

Lets start with the shape of an outbreak. When disease researchers hear about a new threat, one of the first things we do is draw what we call an outbreak curvea graph showing how many cases have appeared over time. Although the shape can vary a lot, it will typically include four main stages: the spark, growth, peak, and decline. In some cases, these stages will appear multiple times; when the swine flu pandemic arrived in the UK in April 2009, it grew rapidly during early summer, peaking in July, then grew and peaked again in late October (well find out why later in the book).

Despite the different stages of an outbreak, the focus will often fall on the spark. People want to know why it took off, how it started, and who was responsible. In hindsight, its tempting to conjure up explanations and narratives, as if the outbreak was inevitable and could happen the same way again. But if we simply list the characteristics of successful infections or trends, we end up with an incomplete picture of how outbreaks actually work. Most things dont spark: for every influenza virus that jumps from animals to humans and spreads worldwide as a pandemic, there are millions that fail to infect any people at all. For every tweet that goes viral, there are many more that dont.

Influenza pandemic in the UK, 2009

Data from Public Health England

Even if an outbreak does spark, its only the start. Try and picture the shape of a particular outbreak. It might be a disease epidemic, or the spread of a new idea. How quickly does it grow? Why does it grow that quickly? When does it peak? Is there only one peak? How long does the decline phase last?