INCA APOCALYPSE

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Covey, R. Alan, 1974- author.

Title: Inca apocalypse : the Spanish conquest and the transformation of

the Andean world / R. Alan Covey.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019041868 (print) | LCCN 2019041869 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190299125 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190299149 (epub) |

ISBN 9780197508169 (online)

Subjects: LCSH: PeruHistoryConquest, 15221548. |

IncasHistory16th century. | Andes RegionCivilization.

Classification: LCC F3442 .C783 2020 (print) | LCC F3442 (ebook) |

DDC 985/.02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041868

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041869

For Lauren and Charlotte

Contents

Writing this book has been an intimidating opportunity. The story of the Spanish invasion and colonization of the Inca world is ripe for retelling, but moving off the well-worn path forged by previous authors meant charting a new course through the scholarly thickets that have sprung up in history and archaeology over the past fifty years. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to a number of people who convinced me that I could pick my way through to produce a narrative that asks and answers some new questions, drawing attention to issues that linger almost five hundred years after Francisco Pizarros first expedition to Peru.

Generous mentors shaped my early intellectual and scholarly development, from my parents to my undergraduate professors. Some names that stand out along the way include Paul Goldstein, Roberta Stewart, Roger Ulrich, and John Watanabe. When I reached my graduate studies at the University of Michigan, I had the good fortune to study with Joyce Marcus, who taught me to read Latin American ethnohistory critically. Sabine MacCormack offered a pivotal seminar on South American contact-period literature, and her work on Inca religion and the apocalyptic worldview have informed this book in profound ways. Kent Flannery, Jeff Parsons, and Bruce Mannheim guided me with their Andean expertise as I was learning to make my way in Peru. Brian Bauer, Chip Stanish, and Mike Moseley gave me my start in Andean archaeology, welcoming me onto their projects and helping to steer me toward my own research. Brian in particular has been an inspiring colleague to work with in the Cuzco region, where I enjoyed the company of several other excellent researchers, including Kenny Sims, Vronique Blisle, Allison Davis, and Miriam Aroz Silva.

Since leaving Ann Arbor, I have passed through several other anthropology departments as my career has taken its winding journey. In every department, I have had brilliant colleagues who offered inspiration and support. At the American Museum of Natural History, Craig Morris supervised my postdoctoral research, but Bob Carneiro, Elsa Redmond, and Chuck Spencer generously read early manuscripts and gave important career advice. At Southern Methodist University, David Freidel and David Meltzer helped me to get my bearings as an assistant professor, and Deborah Nichols provided guidance while I was at Dartmouth College. In my current position at the University of Texas, I am fortunate to have colleagues whose work carries from pre-Hispanic cultures, across the ruptures of European colonization in the Americas. It has been a pleasure to work with Maria Franklin, Enrique Rodrguez-Alegra, Mariah Wade, and Sam Wilson, as well as many other UT faculty.

The actual work of researching and writing this book took place at UT, and I am grateful for a semester-long leave in 2017 that allowed me to pursue the project full-time. My editor, Stefan Vranka, has been a patient advocate throughout the process or writing and revision, and I thank the staff at Oxford University Press for the logistical support during production. As I have tried to make meaning of a new collection of primary sources and recent scholarship, several colleagues have listened thoughtfully to unprocessed ideas about the project, including Brad Jones, David Carballo, Kylie Quave, Steve Kosiba, and my sister Catherine Covey. The anonymous reviewers of the book proposal and first manuscript draft helped to make a better and more readable final product, and I thank Brian Bauer and Chris Heaney for sacrificing huge amounts of their time to read the manuscript and help me to articulate what the Inca apocalypse was about.

Finally, I thank my wife and daughter for their support along the way. To Lauren for helping me to find writing time, for listening to book talk that spilled over from the work day, and for reading chapters with a critical eye and gentle tone that helped me to tell a more coherent story. And to Charlotte, a child who asks important questions about the world, and is always up for venturing out on a quest for answers.

Writing across timeand multiple disciplines and languagespresents some challenges for spelling different names, places, and concepts consistently, while also trying to produce an accessible narrative. I have chosen to use the English spellings for some well-known figuresChristopher Columbus, Isabella I of Castile, Charles Vwhile using common Spanish renderings of other names that appear in colonial texts. I use accepted scholarly spellings for archaeological sites and other places. For key concepts in Quechua, Latin, and Spanish, I use modern versions of terms in the text, but usually preserve the original spelling when quoting from primary sources. Throughout the book, all quotes from non-English sources are my own translations, unless the citation indicates a translated edition.

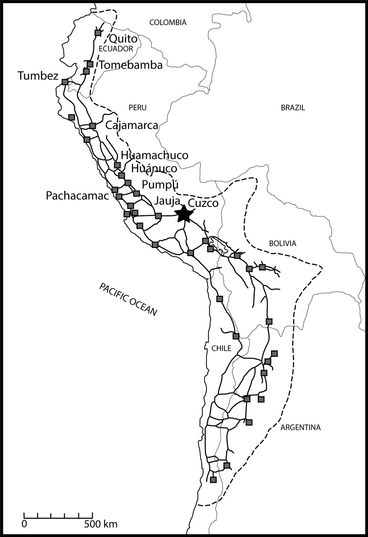

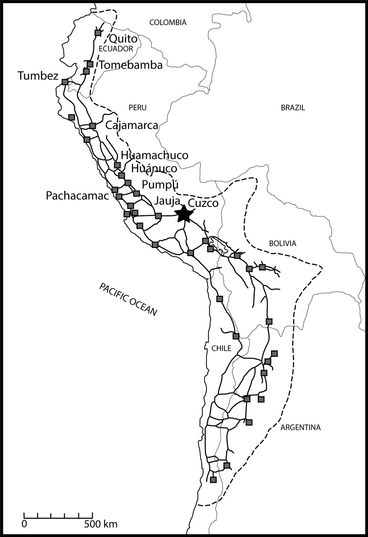

Map 1. The Andean world, showing the approximate territory of the Inca Empire, with major roads, administrative centers, and frontier outposts.

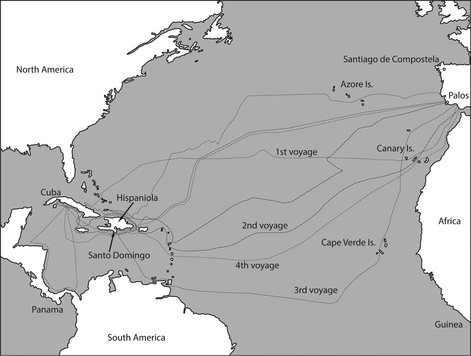

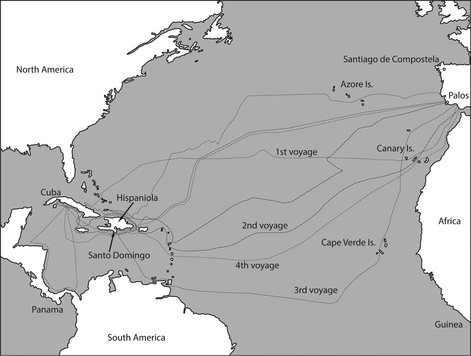

Map 2. The Mediterranean world, showing the territories of Castile and Aragn in 1492.