1998 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

This book was set

in Minion by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Design by April Leidig-Higgins

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shapiro, Karin A. A New South rebellion: the battle against convict labor in the Tennessee coalfields, 18711896 / Karin A. Shapiro.

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8078-2423-2 (cloth: alk. paper).

ISBN 0-8078-4733-x (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Labor disputesTennesseeHistory19th century.

2. Coal minersTennesseeHistory19th century.

3. Convict laborTennesseeHistory19th century.

I. Title.

HD5325.M615S48 1998 97-39125

331.51dc21 CIP

02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1

For Edward

ILLUSTRATIONS

24 A. M. Shook, James Bowron, and Nathaniel Baxter

26 B. A. Jenkins and E. J. Sanford

28 Coal Creek miners

39 James A. Shook School, Tracy City

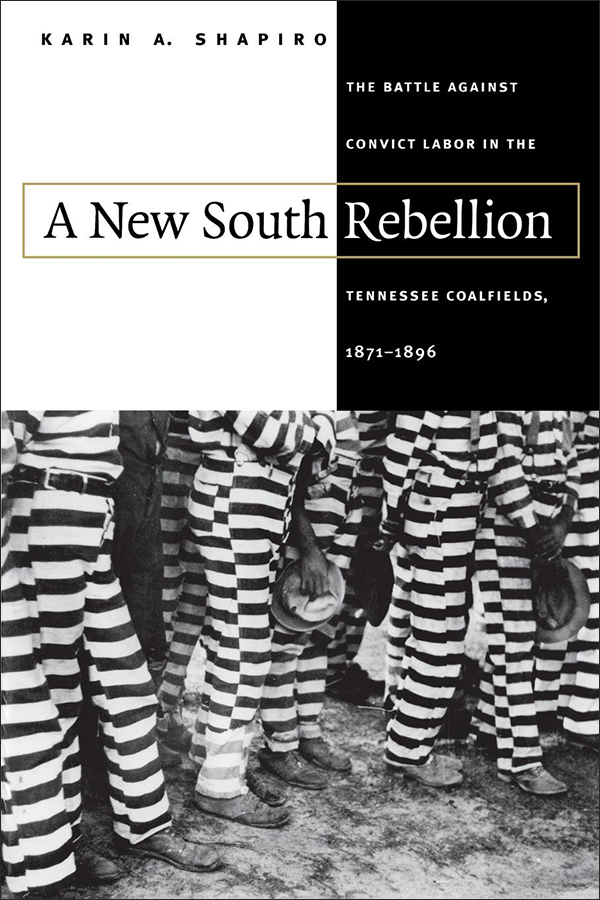

50 Convicts at Tracy City, 1880s

67 Convicts tending coke ovens in Grundy County, 1880s

70 Escaped convict captured by Tracy City guards, 1880s

76 The Briceville stockade

86 Eugene Merrell

90 Governor John Buchanan

96 William Webb

98 Public meeting of miners and residents of Coal Creek Valley

100 Poster advertising a grand mass meeting

115 Commissioner of Labor George Ford

146 Advertisement based on the reward for capturing convicts

154 Fort Anderson on Militia Hill, Coal Creek

156 Poster for celebratory picnic in Briceville, 1892

157 Coal Creek woman

164 Poster advertising the Briceville Cooperative Mine, 1892

176 Thomas F. Carrick, early 1930s

181 The stockade at Inman

188 Miners in the hills surrounding Coal Creek, August 18,1892

194 General Samuel T. Carnes

201 1892 Republican campaign poster

204 Militia Company C at Coal Creek, August 1892

MAPS

17 2.1. The Tennessee Coalfields

18 2.2. The Coal Creek District

19 2.3. The Tracy City District

80 4.1. The Mines in and around Coal Creek, 1890s

88 4.2. Anderson County Coal Towns and Their Surroundings

119 5.1. Tennessee's Political Divisions

175 7.1. Mid-Tennessee Coal Towns and Their Surroundings

Growing up and receiving my initial education in South Africa, I learned early on that political economy and social experience are inextricably intertwined. This lesson was reinforced as I began graduate studya moment when calls for the integration of social and political history were on the rise. One of the central goals of this narrative has been to heed these scholarly pleas. One simply cannot understand the persistence of convict mining in late-nineteenth-century Tennessee, or the dynamics of unionization in the states mining regions, or the willingness of free coal miners to take up arms against the institution of convict labor, or their unwillingness to engage state troops in outright battle, without close attention to political economy and ideology. The vagaries of state and local politics mattered in the coalfields, both to mining magnates, who came to assume that the state would help them maintain a cheap and dependable supply of labor, and to free miners, who expected a Populist government to live by its promises to safeguard what they considered the God-given rights of American workers.

Over the course of writing this book, I have received crucial assistance from a number of institutions and funding agencies. Without the financial support of the Fulbright Program, Yale University, and South Africas Human Sciences Research Council and Ernest Oppenheimer Memorial Trust, I might never have become an American historian. Their generosity enabled me to cross the Atlantic for my graduate education. Additional grants from the American Historical Association, Yale University, the University of the Witwatersrand, and the Human Sciences Research Council funded various research trips.

Most of my excursions were to libraries and archives in the American South, where several archivists and historians went out of their way to be helpful. I particularly want to thank Marilyn Hughes, Wayne Moore, Fran Schell, and Ann Alley at the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville; Steve Cotham, Ted Baehr, and Sally Polhemus at Knoxvilles Lawson McGhee Library; Marvin Whiting at the Birmingham Public Library; Mary Harris at the Anderson County Courthouse in Clinton; Henry Mayer in Louisville, Kentucky; and Anne Armour at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. In Tuscaloosa, Jeff Norrell greatly aided my exploration of the University of Alabamas holdings. In Knoxville, Fred Wyatt of the Coal Creek Mining & Manufacturing Company gave me access to his companys records. John Gaventa, of east Tennessees Highlander Center, provided me with a copy of James Dombrowskis unpublished manuscript about the mining troubles in Anderson and Grundy Counties, Fire in the Hole. Local historians Katherine Hoskins and William Ray Turner were exceedingly generous with their time, knowledge, and resources, with the latter magnanimously sharing his remarkable photographic collection. They and Darby White of the Coal Creek Mining & Manufacturing Company made sure that I saw more of Tennessee than the states libraries and archives. During the last few months of intense work on my manuscript, Catherine Higgs chased down many obscure bibliographic references with amazing speed and cheerfulness.

The skill and talent of the people who helped me with my research was matched by those who lent a hand in the production process. Karina McDaniel and Santu Mofokeng reproduced the photographs; their mastery in this regard speaks for itself. Phillip Stickler and Wendy Job ably generated the maps, and Celeste Mann and Arlene Harris both gave freely of their considerable computer and administrative expertise. It has been a pleasure working with such professionals.

At the UNC Press, Ive had the good fortune to work with Pamela Upton and Alison Tartt, who deftly shepherded the manuscript through its final stages. I am particularly grateful to Lew Bateman, the Presss executive editor, who has manifested great faith in this study from his first encounter with it.

My scholarship has been shaped in untold ways by the intellectual communities in which I have learned my trade. As an undergraduate at the University of the Witwatersrand, I was introduced to the historical craft by Bruce Murray and Charles van Onselen, who imparted a love and respect for the discipline. Though I have wandered far from their areas of expertise, they have continued to read my work and offer valuable advice.

For old friends from my years as a graduate student in New Haven, the acknowledgment of this debt has been long in coming. Thanks are especially due to Cecelia Bucki, Jackie Dirks, Dana Frank, Toni Gilpin, Stan Greenberg, Julie Greene, Leif Haase, Yvette Huginnie, Reeve Huston, Chris Lowe, John Mason, William Munro, Silvie Murray, Gloria Naylor, Ruth Oldenziel, Karen Sawislak, Brian Siritsky, and Brenda Stevenson. John Blassingame and Gerry Jaynes welcomed me into Yales Afro-American Studies Masters Program and guided me through my first two years of graduate work. After I began my dissertation research, Bill Cronon offered invaluable advice about statistical and census matters. More recently, friends in South Africa were wonderfully warm in welcoming back a peripatetic soul and in providing both a congenial and intellectually exciting place to writeespecially Russell Alley, Ann Bernstein, Phil Bonner, Belinda Bozzoli, Jim Campbell, Peter Delius, Deborah James, Paul La Hausse, Phyllis Lewsen, Isak Niehaus, Sue Parnell, Patrick Pearson, Deborah Posel, Jane Starfield, and Sue Valentine. Encouragement from my family has also been indispensable. My siblings, Colin, Mervyn, and Deena, my mother-in-law, Carolyn Balleisen, and especially my parents, Lionel and Joy Shapiro, have provided unfailing support over the years, often from thousands of miles away.