Acknowledgments

I am indebted to a number of individuals and institutions that helped shape this book. The Harry and Lynde Bradley Foundation and The Ohio State University both provided generous support at critical junctures for research and travel expenses; without this help, this project might never have been completed. I am also grateful to the staffs of the National Archives at College Park, MD, and the Reagan, Carter, and Ford Presidential Libraries for assisting a relative newcomer to archival research. I am also grateful to the family of Paul A. Nitze for granting me permission to access Mr. Nitzes papers and to the staff of the Library of Congress for helping me navigate them.

My editor, Michael McGandy, deserves special mention for being willing to engage so thoroughly with my initial proposal and manuscript. Mr. McGandys incisive comments and suggestions did a great deal help me improve my initial efforts and his belief in the value of the work helped inspire me to finish it.

I have benefited from excellent mentors throughout my time in academe. At Vassar College, Prof. Robert Brigham provided my first real to exposure to the history of U.S. foreign relations. He taught me many of the critical elements of historical thinking and supported my interests in arms control and intelligence studies. At Ohio State, Prof. Robert McMahon helped me hone these skills and pushed me to make bold arguments where the evidence demanded it. Also at Ohio State, Prof. Peter Hahn provided a model of professional and academic integrity; he encouraged me to strive for the highest standards of rigor and clarity.

Numerous colleagues have helped shape my thinking and arguments about many aspects of this work. I am especially grateful to Prof. David Stebenne and Prof. Jennifer Siegel of The Ohio State University; Dr. David Hadley; and Dr. Ronald Granieri, Dr. Ted Keefer, Dr. Glen Asner, and Dr. Erin Mahan of the Historical Office of the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

The views expressed in this book are the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government Accountability Office or the United States government.

Introduction

THE PROMISE OF CONTROL

On October 26, 1974, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger found himself in Moscow with a Soviet artillery piece pointed at him. Kissinger had been negotiating with the general secretary of the Communist Party (and de facto leader of the Soviet Union) Leonid Brezhnev and his foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko. The subject was arms control: specifically to limit so-called strategic weapons, the largest missiles and bombers that made up the bulk of both countries nuclear arsenals. The United States and Soviet Union had signed the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (known as SALT I) two years earlier but its terms were limited, both in scope and duration. Both parties hoped to negotiate a more comprehensive, permanent, follow-on agreement (commonly referred to as SALT II). By 1974, however, progress on such an agreement had come to a standstill. After Gerald Ford became president, Kissinger hoped to get negotiations back on track. Doing so required meeting with Brezhnev in his country and on his terms.

Kissinger was accustomed to dealing with Brezhnev, whose bon vivant demeanor concealed a tough, patient negotiator. But by 1974, Brezhnevs age of 67 had begun to take a toll on his mental acuity. Though still capable, he would fidget in long meetings, showing off trinkets and tchotchkes; conversations with him tended to meander. On this day, Brezhnev revealed a tabletop-sized artillery piece during the discussion and began to play with it. He claimed that it worked but that he did not know how. He alternated pointing the gun at Kissingers aide and at the secretary of state himself. Gromyko, trying to preserve some semblance of decorum, suggested that Brezhnev point the gun at him instead of their

If Brezhnevs antics exasperated Kissinger, he did not show it. Frustration quickly became one of the defining features of the SALT negotiations. Subsequent negotiations did not change this dynamic, which remained true well after Kissinger left office. Brezhnev could easily have been expressing his own frustration and boredom with what was among the most complex and intractable issues of the day.

As foreign policy initiatives go, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks seem to stand apart. The negotiations set many precedents for modern arms control, yet most of the terms of the SALT I and II treaties expired after a few years or never went into effect at all. Arsenals with the destructive potential the Soviet Union and United States possessed had never existed before, and attempts to stop a runaway arms race such as this were virtually unprecedented. At times the fate of the entire world seemed to hang in the balance. Though the stakes seemed high, scholars continue to debate just how much the agreements actually changed the nuclear arsenals of each superpower.

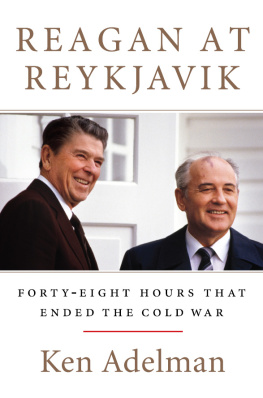

For these reasons, the SALT agreements rarely receive top billing when scholars review the history of arms control. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and the Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty (START) are better known (and better studied) for the role they played in the end of the Cold War. Given their enduring character and the drastic reductions in arms they brought, the prominence of these treaties seems justified. Their negotiating history is equally memorable, characterized by dramatic summit meetings, negotiating breakthroughs, and supposedly visionary leaders operating within a dynamic international environment.

Compared to these events, SALT was a slog. Its negotiations took place during an era of stagnation and relative (though deteriorating) international stability, its pace was often glacial, and the process itself was deeply frustrating, even traumatic, for those involved. The INF and START negotiations and the treaties they produced were very different from SALT, but this was deliberate: many of the negotiators involved bore scars from a decade of fighting over SALT issues. By the time of the 1985 summit meeting between President Ronald Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, virtually every weapon under discussion had featured in SALT negotiations at some point. Some of these systems were developed explicitly in response to the terms of or trends exposed by the SALT negotiations. Both parties brought with them the ugly political baggage of over fourteen years of debates over how to shape and control the nuclear balance and which party bore more of the blame for the status quo. An entire generation of policymakers cut their teeth on these debates, arguing in a vocabulary (since faded into obscurity) of strategic superiority, counterforce targeting, and the window of vulnerability.

Though the issues at play were often abstract and technical, the SALT negotiations were a human process. Specific individuals shaped the negotiations as much as any technological development. Some, like Kissinger, used the negotiations to navigate between opposing groups: on one side a restive domestic populace that was deeply dissatisfied with the arms race and on the other powerful interest groups committed to the Cold War. Some, like President Jimmy Carter, saw the opportunity to secure a legacy as a peacemaker without imposing compromises that might alienate important constituencies. Others, such as the statesman and longtime negotiator Paul Nitze, saw in the negotiations a vessel for their worst fears of a deteriorating balance of power between East and West. And some, like President Ronald Reagan, saw a deeply flawed process that was likely too compromised to achieve a positive outcome that they would rather break than bend any further. Personalities, political exigencies, and occasional human foibles all exerted profound influences on the process. The SALT negotiations most significant legacies developed as a result of the perspectives these individuals brought to bear.