Copyright 2014 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 18 17 16 15 14

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8262-2000-4

ISBN-13: 978-0-8262-7301-7 (electronic)

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Design and composition: Jennifer Cropp

Printing and binding: ThomsonShore, Inc.

Typeface: Minion

INTRODUCTION

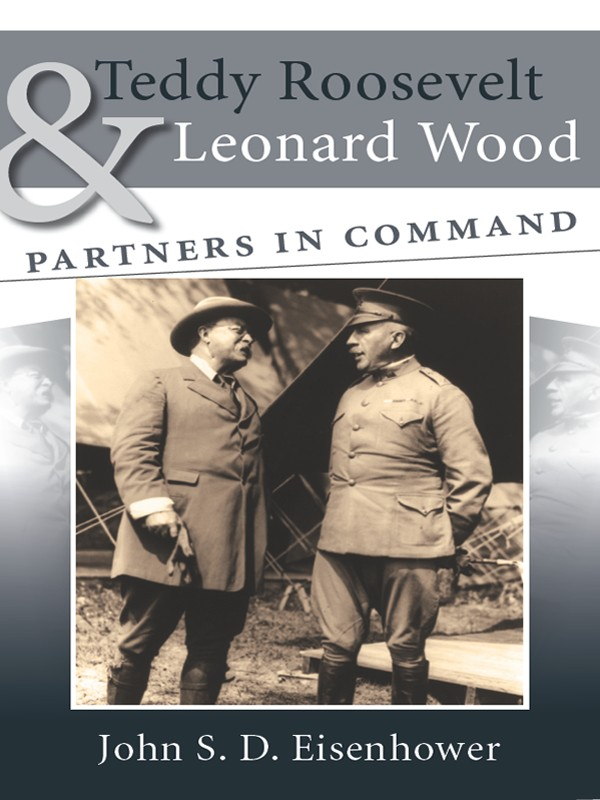

This is the story not of two men, but of a friendship, an association. President Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood, two remarkable men, were the leading proponents of American strength and power during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Greatly different in personality, they shared an obsession with the role of war in the promotion of a glorious American destiny. They went so far as to believe in the benefits of war itself.

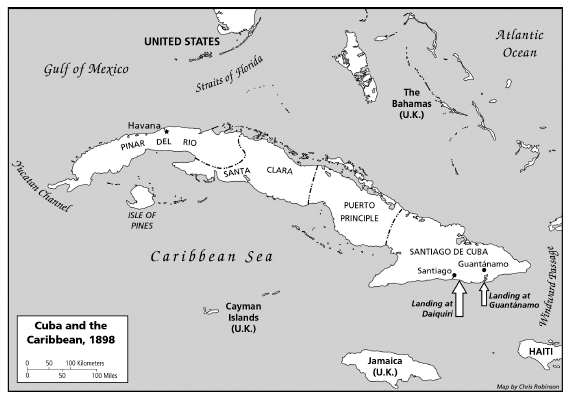

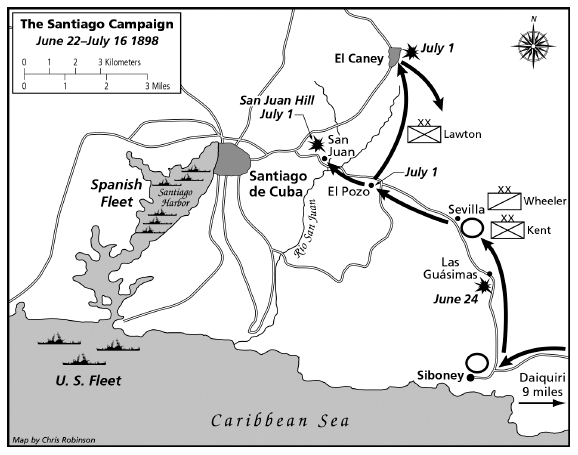

Though highly influential at the time, their partnership has been forgotten or at least relegated to the memories of soldiers and military historians. Roosevelt has been remembered for his heroic action at the Battle of San Juan Hill, Cuba, as part of the 1898 SpanishAmerican War, but few remember that he served under Wood. The Rough Riders, formally known as the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, fought bravely, though overblown by the prose of reporter Richard Harding Davis. Other regiments contributed as much to that victory, perhaps more, but to the public, the name San Juan Hill belongs to Teddy Roosevelt.

The United States easily defeated Spain in the socalled splendid little war, but success was achieved principally because of the weakness of the Spanish, who were by now a thirdrate power. The American expeditions were full of confusion. Supplies, transportation, proper food, training, and even modern rifles were missing. Thus, when Roosevelt became president of the United States in 1901, one of his goals was to reorganize the Army and the Navy, particularly the Army. Aided by that most capable secretary of war, Elihu Root, he set out to rectify organizational evils under which the Army had suffered throughout its history. Never one to forget his friends and allies, TR also arranged for Wood, a Regular Army captain in the Medical Corps, to keep his wartime rank of major general.

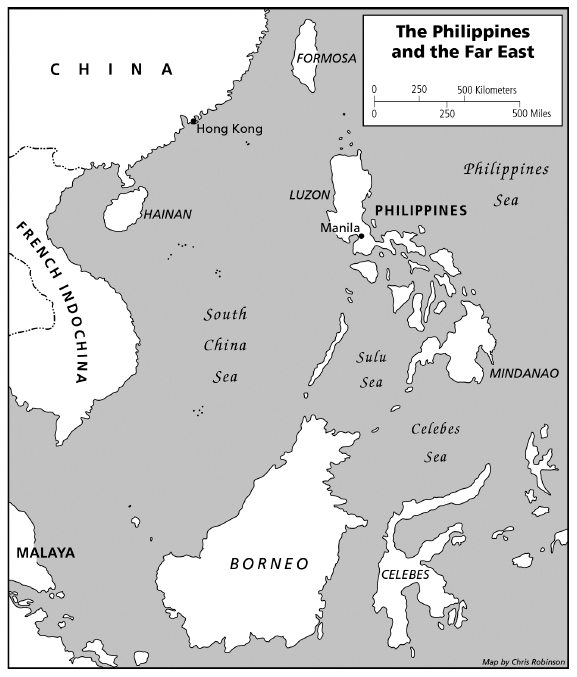

As a young general, jumping over hundreds of more senior officers, Wood justified the president's confidence. After serving as governor of Cuba and later the Moro Province of the Philippines, he was appointed Army chief of staff under President William H. Taft in 1910. There his drive was indispensable. Although TR and Root had set the organizational groundwork for a modern progressive army on paper, the implementation of their changes had met passive resistance from the conservatives, especially the technical services, and little had been done until the arrival of Wood. He possessed the strength necessary to put real teeth in Roosevelt's reorganization. He made Roosevelt's changes actually work.

The final achievement of this partnership was the most important, the leadership of the socalled Preparedness Movement in the days before the American participation in the Great War. The War Department hierarchy had been restructured, but to protect itself against threats from without, the United States needed troops. Even before the outbreak of the European war in August 1914, TR and Wood were painfully conscious of how weak the Army was, its mobile combat force limited to about twenty thousand troops, in contrast to millions in the armies of Europe. Even after the war broke out, the United States still failed to react in any noticeable manner. By then Wood was no longer chief of staff, but he was still commander of the Army's allimportant Eastern Department, and in that post he was able to do much. With former president Roosevelt's enthusiastic supportand President Woodrow Wilson's toleranceWood founded the great training program, the first and most noted camp being at Plattsburg, New York. His pioneering in training young officerssniffingly but unfairly called ninetyday wondersproduced the critical corps of young officers who did so much to provide leadership when the United States was drawn into the conflict in 1917.

Unfortunately, the Preparedness Movement ran counter to the policies of President Wilson, who regarded the act of expanding the Army as a threat to his ambition to appear on the world stage as a peacemaker. To make matters worse, the public statements of both Roosevelt and Wood were no help in winning Wilson's support. Roosevelt, who showed contempt for Wilson's neutrality, made personal remarks about the president's moral and even physical courage. Wood's jeremiads were more restrained, but they still went beyond the limit of what was generally considered proper for an officer in uniform. Wilson took these attacks with remarkable equanimity, but he exacted his revenge when the United States entered the war. He denied both Wood and Roosevelt their heart's desire, the opportunity to go to France and participate in the war against the kaiser's Imperial Germany.

On the personal side, the friendship between president and general was deep, even though they were in early middle age when they first met at a Washington social event in 1897. Roosevelt, at forty years of age, was the elder by two years; furthermore, he was already a national figure, the assistant secretary of the Navy; Wood, on the other hand, was only a captain in the Army Medical Corps, albeit personal physician to President William McKinley. It required all of TR's influence in high places to induce Secretary of War Russell Alger to permit the organization of the Rough Riders in 1898. But Roosevelt was cognizant of his own military limitations, and he insisted that Wood should be the colonel of the regiment, with Roosevelt serving under him as his lieutenant colonel.

Once in uniform, however, Wood was Roosevelt's unquestioned boss for those few months of 1898, despite the public's perception of their unit as Roosevelt's Rough Riders. At the end of the Cuban campaign, when Roosevelt left, their intimate service together came to an end. But their intimacy survived. Throughout the rest of their lives, they acted as if there were no gap in seniority between them. Wood was not above speaking his mind in their correspondence. Once at least he even mildly chastised the president when the latter seemed to renege on what Wood had considered an understanding.

Neither man was prone to introspection, and the way they regarded themselves individually has an amusing aspect. Roosevelt, the master politician, liked to think of himself primarily as a soldier; he insisted on being addressed as Colonel even after leaving the presidency. Yet TR would have been a disastrous Regular Army officer, for the allimportant quality of discipline was not in him. By contrast, Wood, a firstrate soldier, grew to regard himself as a capable politician. In fact, he was nearly as ineffective in that area as his great forebear Winfield Scott, in the first half of the nineteenth century.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.