Contents

Guide

Bryan Appleyard

The Car

The Rise and Fall of the Machine that Made the Modern World

For Ada Shun-Shin

Everything in life is somewhere else, and you get there in a car.

E.B. White

Introduction THE LAST SPACE OF FREEDOM

Cars internal-combustion-engined (ICE), driver-controlled vehicles are scheduled to die in 2030. They will then be 145 years old. The policy of governments and companies is to replace them with EVs, electric vehicles, which will then be replaced by AVs, semi- or fully autonomous vehicles. Not long thereafter, smart cities will control urban and suburban traffic movement and smart motorways will control the rest.

These new vehicles might still be known as cars. But, apart from obvious similarities like wheels and bodywork, they will be something quite different. EVs do not need gears this alone transforms the experience of driving whether you are used to an automatic or a manual gear change. But, in any case, they are just one step on the road to AVs in which the skills of the driver become increasingly redundant and, finally, irrelevant. AVs will be another step on the road to machines that nobody can seriously describe as cars mobile living rooms or offices or even, according to IKEAs AV designers, cafs or hotels. The world made by cars, the cars we have known, loved and hated, the cars that engaged our feelings and senses, that gave us previously unimaginable forms of freedom, is ending.

In their brief ascendancy cars have dominated every aspect of public and private life environmental issues from global warming to pollution of the air we breathe, politics by the power of their industrial wealth and their transformation of societies and lives, and, finally, they have occupied the summit of consumer society as the ultimate objects of desire. They have also permanently changed our understanding of space, time and nature.

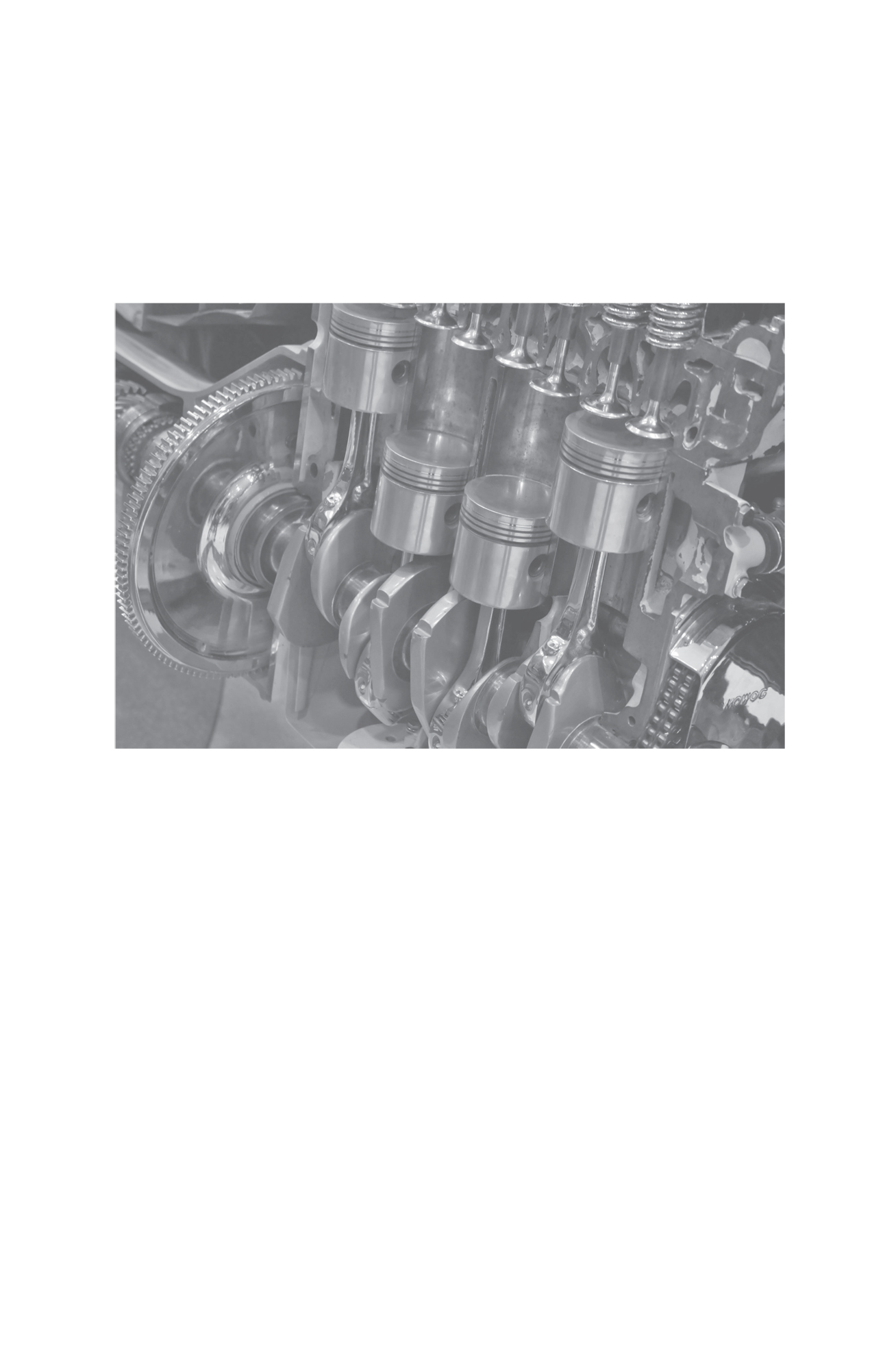

The ICE car is the defining product of the industrial age that began in the early eighteenth century. To drive one is to be connected to steel and oil, rubber, plastic and glass, and a fabulous electro-mechanical ballet of sparks, cylinders, gears and springs, all operated by the movements of the drivers feet and hands. Giant factories employing thousands of workers have built these vehicles ever since Henry Ford opened the Highland Park plant in Detroit in 1910. Cars are, as management theorist Peter Drucker put it, the industry of industries.

Various technologies the personal computer, the mobile phone, the stirrup, aircraft, freight containers are routinely said to have changed the world. But none of them has intruded so imperiously, so ruthlessly into the life and landscape of our planet as the car. Cars have redesigned cities and conquered the countryside, etching the landscape with networks of roads, service stations, parking lots, fast-food outlets, shopping malls and motels. They have remade industries and globalised economies. They have turned what were once strenuous journeys by foot or horse into almost effortless, air-conditioned voyages along smoothly metalled roads. They have subdued the wilderness and turned it into an attraction.

There are 1.4 billion vehicles including buses and trucks on the worlds roads. They cruise the rural land they seized, they fill city streets, consigning pedestrians to a narrow strip of pavement allocated to the activity of walking. The thousands of tons of metal, fuel and fumes that occupy the road are now barely noticed. This astonishing annexation of urban space has become normalised it has become, like the ground, the sky, the air, a condition of our existence. Perhaps that is why people seldom say cars changed the world; it would be like saying oxygen changed the world or asking a fish for its opinion of water. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say cars made this world, the one in which we now live.

Cars have also remade people. They are the ultimate prosthetics, extending human capabilities across physical and mental dimensions. They allow us to move at hitherto unimaginable speed with unprecedented freedom and to do so in a steel cocoon replete with sophisticated comforts.

Cars take us out into the world while simultaneously sustaining our solitude. By replacing maps and providing the rudimentary facts of place names and road numbers, satellite navigation systems have relieved us of the burden of knowing where we are. By seating us in a closed box, cars have relieved us of the burden of others. The car, unlike the horse, the carriage or even the train, is a world of its own, a physically and psychologically sealed zone. This was noted by that most mordant observer of late modernity Michel Houellebecq in his novel The Map and the Territory (2010). He called the car one of the last spaces of freedom for humanity.

In this free zone we are released from the conformity demanded by the eyes and judgements of others. One survey found that two thirds of Americans sing in their cars. As though, remarks Matthew Crawford in his book Why We Drive, we were in the shower! Crawford also notes a special kind of peace that descends on the lone commuting driver because he does not have to do anything else but drive. Alone in their automotive prosthetics, humans find a fulfilment that is elsewhere denied them.

Then there is the sheer joy of driving. Researchers into human happiness have been surprised to find that people derive enormous pleasure from driving. This is reflected in the tactile, sensuous and dynamic delights celebrated in contemporary car advertising. Beyond that there is the thrill of speed, of control, the giddy feeling of connection with the road, the gears, the tyres, the clutch, the engine, and the combination of aggression towards and cooperation with other drivers, the exhilaration of risks taken and avoided, and cyclists, road hogs or boy racers defeated, of toying with the law over speed limits or amber lights, of corners well taken.

This internal freedom is matched by the external freedom provided by the car. Freedom was the unique selling proposition of the very first cars: freedom to roam, to make your own way into, as Henry Ford put it, Gods great open spaces. Before the car, humans were either restricted to slow, punishing walks from their homes or to cities full of horse shit and disease. The car was not only human-liberating, it was also, in usurping the horse, at least to begin with, environment-improving. This was a new form of freedom, which, in turn, was elevated to a more generalised political and social freedom, the right to go or be anywhere, to move, to drive. Drive free or die is the motto of Jalopnik.com, an automotive website, drive having become synonymous with live.

But the case for the prosecution has become ever more compelling. The car is now accused of limiting freedom. It denies freedom to those deprived of their land by the construction of highways and to victims of accidents and pollution. It also denies freedom to nature, to the wilderness. We regard the wilderness as good and define it as a place untouched by humans, something distinctively other. We may stare in wonder at the Grand Canyon but it does not stare back. The rational outcome of that is that we should leave the wilderness alone by making it inaccessible to human invasion. Instead, we cut roads through the mountains, deserts and jungles with rest stops, viewpoints, explanatory signs. Cities, meanwhile, are now choked with cars and littered with machines and buildings that feed them with fuel or allow them to park.