Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by James Tormey

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.795.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930887

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.524.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to Michael Tormey.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Elizabeth Wilson of the Special Collections Section of the Hampton Public Library, who introduced me to the information on the American Revolution that was available on digitized copies of the Virginia Gazette. Additional resources were available in records at the Hampton Library, accessible through use of the Swem Library Index. At the Swem Library, Mary Molineaux helped me find information on the Barron family, including the image of James Barron, and made available U.S. naval documents of the American Revolution.

Michael Cobb, curator of the Hampton History Museum, provided information on Hampton during the Revolution, particularly information that had been assembled by June Mitchell and Hamilton Sis Evans. Wythe Holt and the museum registrar Bethany Austin were likewise helpful and encouraging. Allan Lambert of the City of Hamptons Engineering Information Technology staff created maps used in this book. Shannon McCall applied her creative talent to produce a drawing of Hampton and its environs in 1775.

Samuel Barron Segar Jr. of Norfolk was especially generous in providing information on the Barron family and their ties to Hampton. His family included men with whom I had served in the U.S. Army Engineer District at Norfolk, and this reinforced my interest in the Barron family. Curator Joseph Judge of the Hampton Roads Naval Museum was helpful in finding images of ships in action before the era of photography.

Claudia Jew at the Mariners Museum in Newport News was especially helpful in providing naval images of the Revolutionary War period, as was Jeanne Willoz-Egnor. Marianne Martin of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation facilitated access to the visual resources of Colonial Williamsburg.

I am indebted to my wife, Ann Darling Tormey, for her many helpful suggestions in the writing of this book and for her careful review of the manuscript. I am grateful to my sons, Michael and Barney Tormey, for computer assistance in the production of the manuscript. Without Anns encouragement and Michaels ingenuity, this book would never have been written.

INTRODUCTION

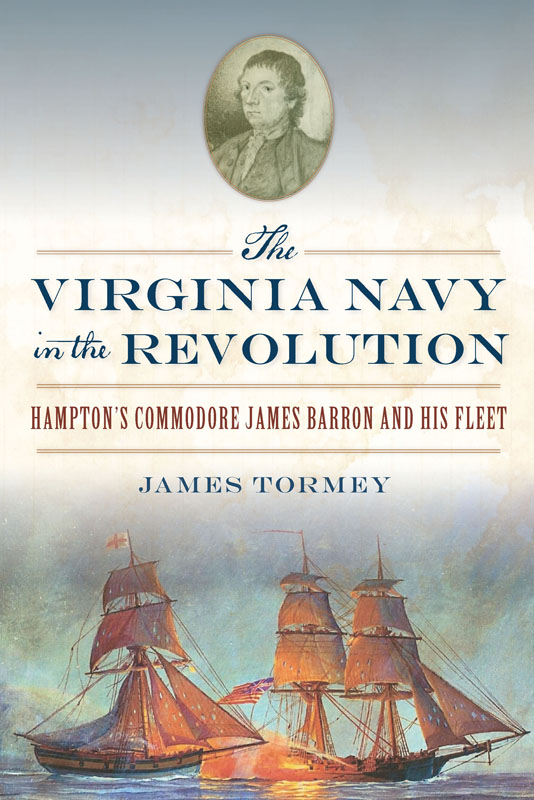

James Barron was a sea captain who fought in the naval conflict between Britain and the thirteen American colonies in the American Revolution. Each state had a navy, and James Barron became a captain, and then a commodore, in the Virginia Navy. The state navies and the Continental navy faced the formidable power of the British Royal Navy in their struggle to keep the coastal and intercoastal waterways of America open. The navy of Virginia had few successes and was nearly destroyed. Nevertheless, Patriot troop and supply movements, as well as civilian commerce, continued despite action by the British navy and British privateers. Ultimately, the naval power of France swung the balance in favor of the American forces and their French allies.

The story of James Barron gives us an insight into how the sailors of the Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia worked and fought for their country. It is also the story of the seaport of Hampton, where James Barron lived and where the Virginia Navy was headquartered.

Chapter 1

COLONIAL TIDEWATER

The earliest Virginia colonists were quick to name the prominent capes that form the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. In doing so, they designated Cape Henry and Cape Charles for the sons of King James. These were prominent landmarks that would be the goal of generations of navigators making their way to Englands Virginia Colony.

Between Cape Charles and Cape Henry lay access to lower Chesapeake Bay. Indeed, it was the gateway to Virginia. There was an array of broad rivers: the James, York, Rappahannock and Potomac. Each of these rivers was wide enough to provide uncluttered access to riparian lands that could be cleared for farming. The mouths of these rivers were distant enough from the fall line, where portaging or locks become necessary, to create a broad coastal plain allowing thousands of acres for farms. Then there were tributaries to the larger rivers that allowed additional farmlands to be reached by the waterways. The topography of Tidewater Virginia could hardly have been more favorable to a people who were so dependent on waterways for transporting their produce.

The availability of farmland and waterways and the emergence of tobacco as a cash crop resulted in a rush to develop Tidewater Virginia after 1624, when Virginia ceased to be a privately owned company. The demand in England for tobacco seemed unlimited, despite the disapproval of King James. Virginia offered a means of satisfying the demand without resorting to foreign imports.

As a commodity, tobacco offered several advantages over grain. It did not require as much land to be cleared for planting, and it resulted in a denser product that required less volume to transport. A mans labor for a year resulted in more money in return for his effort.

Tobacco imports into England had increased from 250 tons in 1628 to 10,000 tons by the end of the seventeenth century. In 1775, they exceeded 50,000 tons. This remarkable growth resulted in tobacco not only being the primary import from the colonies in terms of cash value but also eventually growing large enough that it could be exported by England to other countries in Europe.

Farming large acreages of tobacco appealed to English settlers who were eager to own their own land. The waterways of Virginia provided economical transportation to both the farmers of Virginia and the merchants of England with whom they traded.

Tobacco was transported in hogsheads, a barrel containing about one thousand pounds of tobacco, compressed into a dense volume. The proximity of waterways meant that overland transportationwhich might damage the leaf if transported over miles of dirt roadscould be avoided. The hogshead needed to reach its destination in England within a year or the Virginia tobacco would deteriorate and lose its quality.

In times of war, English vessels were subject to attack by French, Dutch or Spanish privateers, who could find a ready market for prizes seized en route from the colonies to England. As a defense against attack, the English government had devised the convoy system. Royal Navy ships would escort a convoy of as many as two hundred tobacco ships from assembly areas in the lower Chesapeake Bay to their destinations in English ports.