T he idea of giving a badge to be worn in recognition of bravery on the battlefield goes back to the ancient Greeks. The Roman legions then adopted it and established a standardised system of medals that they could wear on their uniforms. These were made of bronze or other metals and the images on them sometimes appeared on Roman gravestones.

The custom was continued by the Byzantine emperors and then picked up by Renaissance Italy and sixteenth-century Germany and seventeenth-century France. The first medals struck in England date back to the Civil War, when Charles I conferred gold medals on John Smith and Robert Welch for saving the Kings Colours at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642. The following year, at Oxford, the king decreed that medals be delivered to wear on the breast of every man who shall be certified under the hands of their commanders-in-chief to have done faithful service in the forlorn hope. Not to be outdone, the Parliamentarians picked up on the idea. The Commonwealth and, then, Charles II issued medals for gallantry in the Dutch Wars, but always on an ad hoc basis.

A standardised system of awards was introduced to the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars. Although some were given for bravery under fire, these were usually awarded for outstanding leadership or distinguished service and restricted to officers. Meanwhile, the East India company introduced a fixed system of campaign medals for its Indian soldiers and, in 1837, instituted its own Order of Merit. This had three grades and, theoretically, a soldier had to have had a lower grade to be promoted to a higher one.

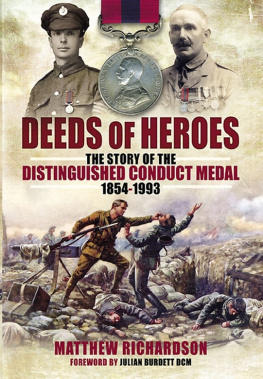

The British government was forced into introducing its own standardised system of awards for servicemen in the Crimean War. This was the first war to be reported in detail in the British press. War correspondents such as William Howard Russell of The Times brought home to the British public the terrible privations suffered by British soldiers and sailors, who were often poorly equipped and badly led but could still be roused to extraordinary feats of bravery. Tales of the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Thin Red Line at Balaklava and life in the trenches in the Russian Winter during the siege of Sebastopol led to growing calls for the recognition of the bravery of British servicemen. In 1854, the Distinguished Conduct Medal was established by Royal Warrant to be conferred on other ranks in the British Army, but not officers. The following year, the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal was instituted by Order in Council for the non-officer ranks of the Royal Navy and Royal Marines. Officers gallantry could always be recognised by admission to the Order of Bath or a mention in dispatches.

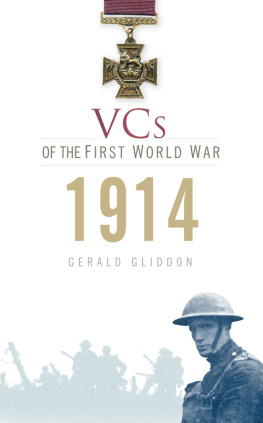

But even this did not slake the publics thirst for awards. The democratic sentiment of the time demanded an award that could be given in recognition of conspicuous bravery regardless of rank. In December 1854, Captain G T Scobell, MP for Bath, called in the House of Commons for the creation of an Order of Merit to be bestowed on persons serving in the Army or Navy for distinguished and prominent personal gallantry. The Duke of Newcastle, then secretary for war, took the idea to Prince Albert, the Prince Consort. They looked abroad for inspiration. Britain and France were allies during the Crimean War and they decided that the new British award for gallantry should be modelled on the Legion of Honour, which had been created by Napoleon in 1802 and was conferred without regard to rank or religion. Queen Victoria herself favoured a single decoration without classes, open to all. But unlike the Legion of Honour, which could also be awarded for civic merit, the British award was open only to the military.

Names suggested for the new award included the Order of Valour and the Military Order of Victoria. Prince Albert came up with Victoria Cross. Then there was the motto to consider. The Reward for Valour the motto of the Indian Order of Merit was one suggestion. Others included Reward for Bravery, For Bravery, To the Brave and Mors aut Victoria Death or Victory. Queen Victoria proposed For Valour. It was to be awarded, the Royal Warrant said, only to those Officers or Men who have served Us in the presence of the Enemy and shall then have performed some signal act of valour or devotion to their Country.

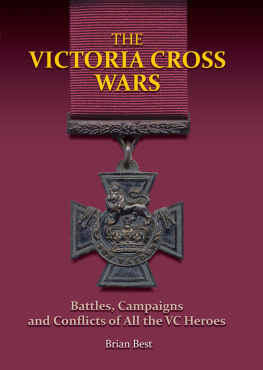

The Queen was also responsible for the simplicity of its design. She favoured the use of bronze over other, more opulent, options. They were made from the cascabels the large knob at the back of a cannon used for securing ropes of two Russian guns captured at Sebastopol. The two guns still stand outside the Rotunda of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, while the remainder of the metal is held in the Small Arms building of the Royal Logistic Corps Defence Store at Donnington, Worcestershire. There is enough left to make 85 more medals.

Designed by the London jewellers Hancocks, the medal is in the form of the Army Gold Cross awarded in the final years of the Napoleonic Wars and since discontinued. The gunmetal was artificially darkened to give a greater contrast to the raised design when polished. On the front, there is the motto, the crown and a lion. On the back, they engraved the name, rank, service number and regiment or ship, along with date of the action it had been awarded for. The Times was not impressed. It said in the issue of 27 June 1857,

Than the Cross of Valour nothing could be more plain and homely, not to say coarse looking. It is a very small Maltese cross, formed from the gun-metal of ordnance captured at Sebastopol. In the centre is a small crown and lion, with which the latters natural proportions of mane and tail the cutting of the cross much interferes. Below these is a small scroll (which shortens three arms of the cross and is utterly out of keeping with the upper portions) bearing the words For Valour the whole cross is, after all, poor looking and mean in the extreme The merit of the design, we believe, is due to the same illustrious individual who once invented the hat.

However, the day before, when the first 62 medals were awarded for bravery in the Crimea, the Baltic and the Sea of Azov at the ceremony in Hyde Park, the public mobbed the recipients for a glimpse of the medal. Its award had been backdated to the beginning of the war. Nevertheless, TheTimes dismissed it as merely tuppence worth of bronze. But that was the point. It was not supposed to be one of those precious, bejewelled baubles conferred by one aristocrat on another. In fact, the originals cost the government 1 to cast, with an additional three shillings (15p) for the engraving on the back.

The award brought with it a pension of 10 a year, with an additional 5 if a second Victoria Cross, or Bar, was awarded. The pension has now been increased to 1,495 a year. Additionally, all officers however exalted their rank were to salute the holder, if in uniform, no matter how lowly the recipient.

Soon after the first Victoria Crosses were awarded, the Queen became concerned about what the recipient should be called. Correct modes of address were all-important. She expressed her concern in a memo to the secretary for war, written in the regal third person.

The Queen thinks that persons decorated with the Victoria Cross might very properly be allowed to bear some distinctive mark after their name, she wrote. But the Victoria Cross was merely a naval and military decoration, not the membership of some distinguished order, as she was used to handing out. Consequently,

VC would not do. KG means a Knight of the Garter; CB a Companion of Bath; MP is a Member of Parliament; MD a Doctor of Medicine, etc., etc. in all cases denoting a person. No one could be called a Victoria Cross. VC, moreover, means Vice-Chancellor at present. DVC, Decorated with the Victoria Cross, or BVC, Bearer of the Victoria Cross, might do. The Queen thinks the last is best.