Published in 2019 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2019 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Young-Brown, Fiona, author.

Title: Plate tectonics / Fiona Young-Brown.

Description: First edition. | New York : Cavendish Square, [2018] | Series:

Great discoveries in science | Audience: Grades 9 to 12. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013139 (print) | LCCN 2018014490 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502643742 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502643841 (library bound) |

ISBN 9781502643964 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Plate tectonics--Juvenile literature. | Geology,

Structural--Juvenile literature. | Earth sciences--History--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC QE511.4 (ebook) | LCC QE511.4 .Y67 2018 (print) | DDC 551.1/36--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013139

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Jodyanne Benson Copy Editor: Michele Suchomel-Casey Associate Art Director: Alan Sliwinski Designer: Christina Shults Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Semnic/Shutterstock.com; p. 4 Fotos593/Shutterstock.com; p. 9 Lynette Cook/Science Photo Library/ Getty Images; p. 10 Ian Cuming/Ikon Images/Getty Images; p. 12 Vadim Sadovski/Shutterstock.com; p. 16 DArco Editori/De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images; p. 17 Lara-sh/Shutterstock.com; p. 19 Dorling Kindersley/ Getty Images; p. 22 Paul D Stewart/Science Photo Library/Getty Images; p. 26 John Crux/Shutterstock.com; p. 28 Jakinnboaz/Shutterstock.com; p. 31 G Brad Lewis/Science Faction/Getty Images; p. 34 William Frederick Mitchell/Wikimedia Commons/File:HMS challenger William Frederick Mitchell.jpg/CC0; p. 37 Unknown/ Wikimedia Commons/File:PSM V29 D322 Gray and milne seismograph with recorder.jpg/CC0; p. 40 Eduards Normaals/Shutterstock.com; p. 47 Tinkivinki/Shutterstock.com; p. 48 Print Collector/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 51 Evikka/Shutterstock.com; p. 54 National Science Foundation/Wikimedia Commons/File:Morgan, W. Jason.jpg/CC0; p. 59 Charles ORear/Corbis Documentary/Getty Images; p. 62 Fritz Goro/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; p. 67 SPL/Science Source; p. 70 Robin2/Shutterstock.com;p. 75 LouieLea/Shutterstock. com; p. 80 Designua/Shutterstock.com; p. 82 Vitoriano Junior/Shutterstock.com; p. 87 ONYXprj/Shutterstock. com; p. 88 USGS/Wikimedia Commons/ File:Bathymetry image of the Hawaiian archipelago.png/CC0; p. 92 Ventdusud/Shutterstock.com; p. 94 Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com; p. 101 Janez Volmajer/Shutterstock. com; p. 104 Mike Korostelev www.mkorostelev.com/Moment/Getty Images; p. 107 Iurii/Shutterstock.com.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

O ne afternoon in February 2018, the rush hour traffic of Mexico City came to an abrupt halt as the ground beneath started shaking violently. People ran for cover as buildings swayed in the 7.2 magnitude earthquake. Fortunately, the damage was minimal and there were no deaths. For some older residents, it was a frightening reminder of the devasting 8.0 earthquake that hit the city in 1985 . That time, they were not so lucky. The city suffered extensive damage, and more than five thousand people lost their lives.

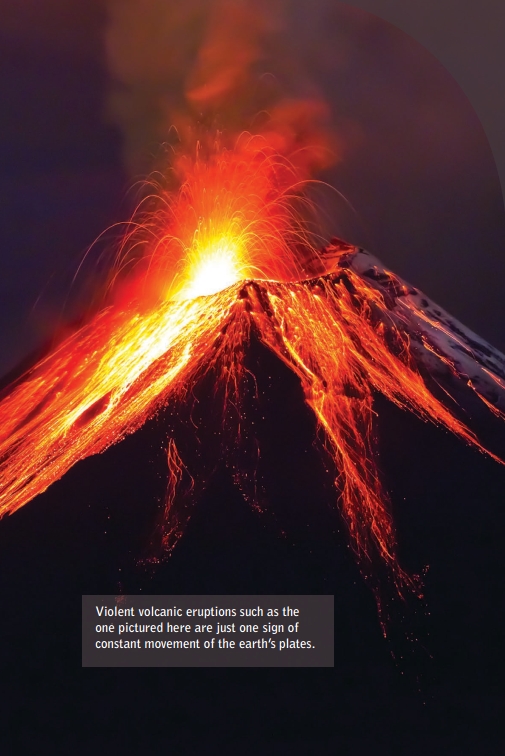

As Mexico City trembled, thousands of miles away, the red-hot lava continued to bubble in Ethiopia. The volcanic Erta Ale, one of the worlds few lava lakes, has been erupting regularly since the 1960s.

Going back a few years, we can visit Honshu, Japan. This island nation is no stranger to natural disasters, but that does not make the widespread damage any less tragic. In March 2011, a powerful 9.0 earthquake off the coast of Tohoku was followed by massive tsunami waves that stood more than 128 feet (39 meters) high and traveled as far as 6 miles (10 kilometers) inland. The waves damaged a nuclear power plant, and people for miles around were forced to flee their homes. Many still have not been able to return. The total death toll was more than fifteen thousand with many more injured or missing.

Volcanic lava in Africa. Earthquakes in Mexico. Tsunamis in Japan. What links these fascinating but often catastrophic events?

The answer is plate tectonics.

It is only fairly recently that we discovered the answer. Not until the 1960s did scientists make a breakthrough that would revolutionize geological studies.

If we travel far back in history, we find countless myths and legends of the earth opening up, of angry gods sending plumes of fire into the sky, of villages being laid waste. The story of the destruction of Pompeii in 79 CE has been told worldwide. Now visitors flock to see the remains in Italy, which offer a snapshot of daily life many centuries ago.

The ancient Romans and Greeks attempted to explain why such things happened as they tried to make sense of nature. The Japanese engraved wood carvings and told tales of the angry fish that caused the waves to engulf the land. For those who lived in areas prone to natural disasters, rebuilding was a way of life.

The Renaissance saw a renewed interest in science. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci collected fossils and wondered how sea creatures could have lived in the mountains. Others drew the first detailed atlases and marveled at how it seemed that different countries could almost slot together.

By the eighteenth century, the fields of geology and paleontology were developing, but they were regarded as hobbies rather than proper science. Finally, the Scotsman James Hutton published a controversial theory that the earth was millions of years old and that the rocks that make up the planets crust were constantly changing as a result of heat, pressure, and erosion.

The Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century triggered new scientific curiosities and advances. Charles Darwin investigated the origins of man and animals. Ocean floors were charted for the first time, and mountains were found deep below the seas. Each new discovery raised new questions.

Then, in 1912 , a meteorologist from Germany made a bold claim. Alfred Wegener argued that all of the continents were once joined together. This, in itself, was not particularly new. Others had suspected as much. However, they had all believed that the continents had been joined by land bridges, now collapsed beneath the oceans. Wegener was suggesting something entirely different: they had all been part of one large mass before they drifted apart.